Collages Read online

1964

VIENNA WAS THE CITY OF STATUES. They were as numerous as the people who walked the streets. They stood on the top of the highest towers, lay down on stone tombs, sat on horseback, kneeled, prayed, fought animals and wars, danced, drank wine and read books made of stone. They adorned cornices like the figureheads of old ships. They stood in the heart of fountains glistening with water as if they had just been born. They sat under the trees in the parks summer and winter. Some wore costumes of other periods, and some no clothes at all. Men, women, children, kings, dwarfs, gargoyles, unicorns, lions, clowns, heroes, wise men, prophets, angels, saints and soldiers preserved for Vienna an illusion of eternity.

As a child Renate could see them from her bedroom window. At night, when the white muslin curtains fluttered out like ballooning wedding dresses, she heard them whispering like figures which had been petrified by a spell during the day and came alive only at night. Their silence by day taught her to read their frozen lips as one reads the messages of deaf mutes. On rainy days their granite eye sockets shed tears mixed with soot.

Renate would never allow anyone to tell her the history of the statues, or to identify them. This would have situated them in the past. She was convinced that people did not die, they became statues. They were people under a spell and if she were watchful enough they would tell her who they were and how they lived now.

Renate’s eyes were sea green and tumultuous like a reduction of the sea itself. When they seemed about to overflow with emotion, her laughter would flutter like windchimes and form a crystal bowl to contain the turquoise waters as if in an aquarium, and then her eyes became scenes of Venice, canals of reflections, and gold specks swam in them like gondolas. Her long black hair was swept away from her face into a knot at the top of her head, then fell over her shoulders.

Renate’s father built telescopes nd microscopes, so that for a long time Renate did not know the exact size of anything. She had only seen them diminutive or magnified.

Renate’s father treated her like a confidante, a friend. He took her with him on trips, to the inauguration of telescopes, or to ski. He discussed her mother with her as if Renate were a woman, and explained that it was her mother’s constant depression which drove him away from home.

He relished Renate’s laughter, and there were times when Renate wondered whether she was not laughing for two people, laughing for herself but also for her mother who never laughed. She laughed even when she felt like weeping.

When she was sixteen she decided she wanted to become an actress. She informed her father of this while he was playing chess, hoping that his concentration on the game would neutralize his reaction. But he dropped his king and turned pale.

Then he said very coldly and quietly: “But I have watched you in your school plays and I do not think you are a good actress. You only acted an exaggerated version of yourself. And besides, you’re a child, not a woman yet. You looked as if you had dressed up in your mother’s clothes for a masquerade.”

“But, Father, it was you who once said that what you liked about actresses was that they were exaggerated women! And now you use this very phrase against me, to pass judgment on me.”

Renate spoke vehemently, and as she spoke her sense of injustice grew magnified. It took the form of a long accusation.

“You have always loved actresses. You spend all your time with them. I saw you one night working on a toy based on an interplay of mirrors. I thought it was for me. I was the one who liked to look through kaleidoscopes. But you gave it to an actress. Once you would not take me to the theater, you said I was too young, yet you took a girl from my school, and she showed me all the flowers and candy you sent her. You just want to keep me a child forever, so I will stay in the house and cheer you up.”

She did not talk like a child angry that her father did not believe in her talent, but like a betrayed wife or mistress.

She stormed and grew angrier until she noticed that her father had grown paler, and was clutching at his heart. Frightened, she stopped herself short, ran for the medicine she had seen him take, gave him the drops, and then kneeled beside him and said softly: “Father, Father, don’t be upset. I was only pretending. I was putting on an act to prove to you that I could be a good actress. You see, you believed me, and it was all pretence.”

These words softly spoken, revived her father. He smiled feebly and said: “You’re a much better actress than I thought you were. You really frightened me.”

Out of guilt she buried the actress. It was only much later she discovered that her father had long been ill, that she had not been told, and that it was not this scene which had brought on the first symptoms of a weak heart.

In every relationship, sooner or later, there is a court scene. Accusations, counter-accusations, a trial, a verdict.

In this scene with her father, Renate condemned the actress to death thinking that her guilt came from opposing his will. It was only later that she became aware that this had not been a trial between father and daughter.

She had, for a few moments, taken the place of her mother and voiced accusations her mother had never uttered. Her mother had been content to brood, or to weep. But Renate had spoken unconsciously a brief for an unloved wife.

It had not been the rebellion of a daughter against a father’s orders she felt guilty of, but her assuming what should have been her mother’s role and place in her father’s heart.

And her father too, she knew now, had not been hurt by a daughter’s rebellion, but by the unmasking of a secret: he had not looked upon Renate as a daughter but as a woman, and his insistence on maintaining her a child was to disguise the companionship he enjoyed.

After this scene, Renate’s father searched for a tutor because Renate had at the same time refused to continue to go to school.

He had a brother who had refused to go to school and had locked himself up in his room with many books. He only came out of it to eat and to renew his supply of books. At the end of seven years he came out and passed his examinations brilliantly and became a professor.

He indulged in one gentle form of madness which did not affect his scholarly and philosophical knowledge. He insisted that he had no marrow in his bones.

Renate’s father thought that his brother would be a good tutor for Renate. He could teach her music, painting, and languages. It would help to keep her at home, away from the influence of other girls. But he explained the professor’s obsession to her, and stressed clearly that she must never refer to bones or marrow as it ignited his irrational obsession.

Renate was naturally strongly tempted to discuss this very mystifying theme, and the marrow madness of her uncle interested her far more than anything else he might teach her.

She spent many days trying to find a tactful way to introduce this theme in their talks together. She did some preparatory research in the library. She discovered that birds have no marrow in their bones. She bought her uncle a canary with a coloratura voice and said: “Did you know that birds do not have marrow in their bones?”

“Yes,” said her uncle, “but neither have I.”

“How marvelous,” said Renate, “that means that you can fly!”

Her uncle was impressed but would not put himself through the test. For fear she might urge him to explore this new concept, he never referred to his handicap again. But before adopting complete silence on this subject he offered her a rational explanation of its cause.

“My mother told me that she became pregnant while still nursing me. Slowly I realized that this other child, my brother, had absorbed all the nourishment away from me, thus leaving me without marrow in my bones.”

WHEN BRUCE FIRST CAME TO VIENNA Renate noticed him because of his resemblance to one of the statue

s which smiled at her through her bedroom window. It was the statue with wings on its heels, the one she was convinced traveled during the night. She observed him every morning while eating her breakfast. She was certain she could detect signs of long journeys. His hair seemed more ruffled, there was mud on his winged feet.

She recognized in Bruce the long neck, the runner’s legs, the lock of hair over the forehead.

But Bruce denied this relationship to Mercury. He thought of himself as Pan. He showed Renate how long the downy hair was at the tip of his ears.

Familiarity with the agile, restless statue put her at ease with Bruce. What added to the resemblance was that Bruce talked little. Or he talked with motions of his body and the gestures were more eloquent than the words. He entered into conversation with a forward thrust of his shoulders, as if he were going either to fly or swim into its current, and when he could not find the words he would shake his body as if he were executing a jazz dance which would shake them out like dice. His thoughts were still enclosed within his body and could only be transmitted through it. The words he was about to say first shook his body and one could follow their course in the vibrations running through it, in the shuffling rhythm of his feet. Gusts of words agitated every muscle, but finally converged into one, at the most two words: “Man, see, man, see here, man, oh man.”

At other times they rushed out in rhythmic patterns like variations in jazz so swift one could barely catch them. He was looking for words equivalent to jazz rhythms. He was impatient with sequences, chronology, and construction. An interruption seemed to him more eloquent than a complete paragraph.

But Renate, having been trained for years to read the unmoving lips of statues, heard the words which came from the perfect modeling of Bruce’s lips. The message she heard was: “What does one do when one is fourteen times removed from one’s true self, not two, or three, but fourteen times away from the center?”

She would start with making a portrait of him. He would see himself as she saw him. That would be a beginning.

They worked together for many afternoons. What Bruce observed was compassion in her voice, what he saw under her heavy sensual eyelids was a diminutive image of himself swimming in the film of emotion which humidified her eyes.

“Come with me to Mexico,” said Bruce. “I want to wander about a little until I find out who I am, what I am.”

And so they started on a trip together. Bruce wanted to put space and time between the different cycles of his life.

It ws during the long drives through hot deserts, the meals at small saffron-perfumed restaurants on the road, the walks through the prismatic markets to the tune of soft Mexican chants that he said, as Renate’s father had said: “I love to hear you laughing, Renate.”

If the heavy rains caught them in their finest clothes, on the way to a bullfight, Renate laughed as if the gods, Mexican or others, were playing pranks. If there were no more hotel rooms, and if by listening to the advice of the barman they ended in a whorehouse, Renate laughed. If they arrived late at night, and there was a sandstorm blowing, and no restaurants open, Renate laughed.

“I want to bring all this back with us,” she said once.

“But what is this?” asked Bruce.

“I am not sure. I only know I want to bring it back with us and live according to it.”

“I know what it is,” said Bruce, spilling the contents of their valises over the beds, and searching for the alarm clock. Then he repacked negligently, and as they drove away, a few hours later, on a deserted road, he stopped, wound up the alarm clock, and left it standing on the middle of the road. As they drove away, it suddenly became unleashed like an angry child, the alarm bell rang like a tantrum, and it shook with fury and protest at neglect.

Sometimes they stopped late at night in a motel which looked like a hacienda. The gigantic old ovens, shaped like cones, had been turned into bedrooms. The brasero in the center of the tent-shaped room threw its smoke to the converging opening at the top. The cold stone was covered with red and black serapes. Renate would brush her long hair. Bruce would go out without a word. His exit was like a vanishing act, because he made no announcement, and was followed by silence. And this silence was not like an intermission. It was like a premonition of death. The image of his pale face vanishing gave her the feeling of someone seeking to be warmed by moonlight. The Mexican sun could not tan him. He had already been permanently tinted by the Norwegian midnight sun of his parents’ native country.

From occasional vague descriptions, Renate had understood that his parents had brought him up in this impenetrable silence. They had a language they talked between themselves and had only a broken form of English to use with the child. They had left him in America at the age of eleven, without any words of explanation, returned to Norway, and let him be brought up by a distant relative.

“Distant he was,” said Bruce once, laughing. “My first job was given to me by a neighbor who owned the candy machines in which kids put a penny and get candy and sometimes if they are lucky, a prize. The prizes were rings, small whistles, tin soldiers, a new penny, a tie pin. My job was to insert a little glue so the prizes would never come down the slot.”

They laughed.

When I met you in Vienna, I was on my way to see my parents. Then I thought: what’s the use? I don’t even remember their faces.”

Before he had left the room, they had been drinking Mexican beer. He said looking at his glass and turning it in his hand: “When you are drunk an ordinary glass shines like a diamond.”

Renate added: “When you are drunk an iron bed seems like the feather bed of sensual Sultans.”

He rebelled against all ties, even the loving web of words, promises, compliments. He left without announcing his return, not even using the words most people uttered every day: “I’ll be seeing you!”

Renate would fall asleep in her orange shawl, forgetting to undress. At first she slept, and then awakened and waited. But waiting in a Mexican hotel in the middle of the desert with only the baying of dogs, the flutter of palm trees by candlelight, seemed ominous. And so one night she went in search of him.

The countryside was dark, filled with fireflies and the hum of cicadas. There was only one small café lit with orange oil lamps. Peasants in dirty white suits sat drinking. A guitarist was playing and singing slowly, as if sleep had half-hypnotized him. Bruce was not there.

Returning along the dark road she saw a shadow by a tree. A car passed by. Its headlight illumined the side of the road and two figures standing by a tree. A young Mexican boy stood leaning against the vast tree trunk, and Bruce was kneeling before him. The Mexican boy rested his dark hand on Bruce’s blond hair and his face was raised towards the moon, his mouth open.

Weeping Renate ran back to the room, packed and drove away.

She drove to Puerta Maria by the sea where they were exhibiting her paintings. And the image of the night tree with its flowers of poison was replaced by her first sight of a coral tree in the glittering sunlight.

It eclipsed all the other trees with the intensity of its orange flowers growing in tight wide bouquets at the end of bare branches, so that there were no leaves or shadows of leaves to attenuate the explosion of colors. They had petals which seemed made of orange fur tipped with blood-red tendrils. It was the flower from the coral tree which should have been named the passion flower.

As soon as she saw it she wanted a dress of that color and that intensity. That was not difficult to find in a Mexican sea town. All their dresses took their colors from flowers. She bought the coral tree dress. The orange cotton had almost invisible blood-red threads running through it as if the Mexicans had concocted their dyes from the coral tree flower itself.

The coral tree would kill the memory of a black gnarled tree and of two figures sheltered under its grotesque branches.

The coral tree would carry her into a world of festivities. An orange world.

In Hait

i the trees were said to walk at night. Many Haitians swore they had actually seen them move, or had found them in different places in the morning. So at first she felt as if the coral tree had moved from its birthplace and was walking through the spicy streets or the zling festive beach. Her own starched, flouncing skirt made her think of the coral tree flower that never wilted on the tree, but at death fell with a sudden stab to earth.

The coral tree dress did not fray or fade in the tropical humidity. But Renate did not, as she had expected, become suffused with its colors. She had hoped to be penetrated by the orange flames and that it would dye her mood to match the joyous life of the sea town. She had thought that steeped in its fire she would be able to laugh with the orange gaiety of the natives. She had expected to absorb its liveliness intravenously. But to the self that had sought to disguise her regrets the coral tree dress remained a costume.

Every day the dress became more brilliant, drenched in sunlight and matching its dazzling hypnosis. But Renate’s inner landscape was not illumined by it. Inside her grew a gigantic, tortured black tree and two young men who had made a bed of it.

People stopped her as she passed, women to envy, children to touch, men to receive the magnetic rays. On the beach, people turned towards her as if the coral tree itself had come walking down the hill.

But inside the dress lay a black tree, the night. How people were taken in by symbolism! She felt like a fraud, drawing everyone into her circle of orange fire.

She attracted the attention of a man from Los Angeles who wore white sailor pants, a white T-shirt, and who was suntanned and smiling at her.

Is he truly happy, she wondered, or is he wearing a disguise too?

At the beach he had merely smiled. But here in the market, the one behind the bullring, he was lost, and he appealed to her. He did not know where he was. His arms were full of straw hats, straw donkeys, pottery, baskets and sandals.

He had strayed among the parrots, the sliced and odorous melons, the women’s petticoats and ribbons. The petticoats swollen by the breeze caressed his hair and damp cheeks. The palm-leafed roofs were too low for him and the tips of the leaves tickled his ears.

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

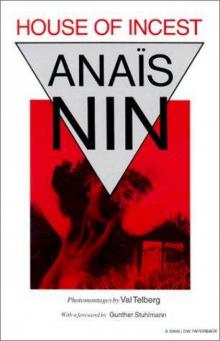

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest