Ladders to Fire Read online

1959

Book I of CITIES OF THE INTERIOR

THIS HUNGER

LILLIAN WAS ALWAYS in a state of fermentation. Her eyes rent the air and left phosphorescent streaks. Her large teeth were lustful. One thought of a negress who had found a secret potion to turn her skin white and her hair red.

As soon as she came into a room she kicked off her shoes. Necklaces and buttons choked her and she loosened them, scarves strangled her and she slackened them. Her hand bag was always bursting full and often spilled over.

She was always in full movement, in the center of a whirlpool of people, letters, and telephones. She was always poised on the pinnacle of a drama, a problem, a conflict. She seemed to trapeze from one climax to another, from one paroxysm of anxiety to another, skipping always the peaceful region in between, the deserts and the pauses. One marveled that she slept, for this was a suspension of activity. One felt sure that in her sleep she twitched and rolled, and even fell off the bed, or that she slept half sitting up as if caught while still talking. And one felt certain that a great combat had taken place during the night, displacing the covers and pillows.

When she cooked, the entire kitchen was galvanized by the strength she put into it; the dishes, pans, knives, everything bore the brunt of her strength, everything was violently marshaled, challenged, forced to bloom, to cook, to boil. The vegetables were peeled as if the skins were torn from their resisting flesh, as if they were the fur of animals being peeled by the hunters. The fruit was stabbed, assassinated, the lettuce was murdered with a machete. The flavoring was poured like hot lava and one expected the salad to wither, shrivel instantly. The bread was sliced with a vigor which recalled heads falling from the guillotine. The bottles and glasses were knocked hard against each other as in bowling games, so that the wine, beer, and water were conquered before they reached the table.

What was concocted in this cuisine reminded one of the sword swallowers at the fair, the fire-eaters and the glass-eaters of the Hindu magic sects. The same chemicals were used in the cooking as were used in the composition of her own being: only those which caused the most violent reaction, contradiction, and teasing, the refusal to answer questions but the love of putting them, and all the strong spices of human relationship which bore a relation to black pepper, paprika, soybean sauce, ketchup and red peppers. In a laboratory she would have caused explosions. In life she caused them and was afterwards aghast at the damage. Then she would hurriedly set about to atone for the havoc, for the miscarried phrase, the fatal honesty, the reckless act, the disrupting scene, the explosive and catastrophic attack. Everywhere, after the storms of her appearance, there was emotional devastation. Contacts were broken, faiths withered, fatal revelations made. Harmony, illusion, equilibrium were annihilated. The next day she herself was amazed to see friendships all askew, like pictures after an earthquake.

The storms of doubt, the quick cloudings of hypersensitivity, the bursts of laughter, the wet furred voice charged with electrical vibrations, the resonant quality of her movements, left many echoes and vibrations in the air. The curtains continued to move after she left. The furniture was warm, the air was whirling, the mirrors were scarred from the exigent way she extracted from them an ever unsatisfactory image of herself.

Her red hair was as unruly as her whole self; no comb could dress it. No dress would cling and mould her, but every inch of it would stand out like ruffled feathers. Tumult in orange, red and yellow and green quarreling with each other. The rose devoured the orange, the green and blue overwhelmed the purple. The sport jacket was irritated to be in company with the silk dress, the tailored coat at war with the embroidery, the everyday shoes at variance with the turquoise bracelet. And if at times she chose a majestic hat, it sailed precariously like a sailboat on a choppy sea.

Did she dream of being the appropriate mate for the Centaur, for the Viking, for the Pioneer, for Attila or Genghis Khan, of being magnificently mated with Conquerors, the Inquisitioners or Emperors?

On the contrary. In the center of this turmoil, she gave birth to the dream of a ghostly lover, a pale, passive, romantic, anaemic figure garbed in grey and timidity. Out of the very volcano of her strength she gave birth to the most evanescent, delicate and unreachable image.

She saw him first of all in a dream, and the second time while under the effects of ether. His pale face appeared, smiled, vanished. He haunted her sleep and her unconscious self.

The third time he appeared in person in the street. Friends introduced them. She felt the shock of familiarity known to lovers.

He stood exactly as in the dream, smiling, passive, static. He had a way of greeting that seemed more like a farewell, an air of being on his way.

She fell in love with an extinct volcano.

Her strength and fire were aroused. Her strength flowed around his stillness, encircled his silence, encompassed his quietness.

She invited him. He consented. Her whirlpool nature eddied around him, agitating the fixed, saturnian orbit.

“Do you want to come…do you?”

“I never know what I want,” he smiled because of her emphasis on the “want,” “I do not go out very much.” From the first, into this void created by his not wanting, she was to throw her own desires, but not meet an answer, merely a pliability which was to leave her in doubt forever as to whether she had substituted her desire for his. From the first she was to play the lover alone, giving the questions and the answers too.

When man imposes his will on woman she knows how to give him the pleasure of assuming his power is greater and his will becomes her pleasure; but when the woman accomplishes this, the man never gives her a feeling of any pleasure, only of guilt for having spoken first and reversed the roles. Very often she was to ask: “Do you want to do this?” And he did not know. She would fill the void, for the sake of filling it, for the sake of advancing, moving, feeling, and then he implied: “You are pushing me.”

When he came to see her he was enigmatic. But he was there.

As she felt the obstacle, she also felt the force of her love, its impetus striking the obstacle, the impact of the resistance. This collision seemed to her the reality of passion.

He had been there a few moments and was already preparing for flight, looking at the geography of the room, marking the exits “in case of fire,” when the telephone rang.

“It’s Serge asking me to go to a concert,” said Lillian with the proper feminine inflection of: “I shall do your will, not mine.” And this time Gerard, although he was not openly and violently in favor of Lillian, was openly against Serge, whoever he was. He showed hostility. And Lillian interpreted this favorably. She refused the invitation and felt as if Gerard had declared his passion. She laid down the telephone as if marking a drama and sat nearer to the Gerard who had manifested his jealousy.

The moment she sat near him he recaptured his quality ofa mirage: paleness, otherworldliness, obliqueness. He appropriated woman’s armor and defenses, and she took the man’s. Lillian was the lover seduced by obstacle and the dream. Gerard watched her fire with a feminine delectation of all fires caused by seduction.

When they kissed she was struck with ecstasy and he with fear.

Gerard was fascinated and afraid. He was in danger of being possessed. Why in danger? Because he was already possessed by his mother and two possessions meant annihilation.

Lillian could not understand. They were two different loves, and could not interfere with each other.

She saw, however, that Gerard was paralyzed, that the very thought of the two loves confronting each other meant dea

He retreated. The next day he was ill, ill with terror. He sought to explain. “I have to take care of my mother.”

“Well,” sai

d Lillian, “I will help you.”

This did not reassure him. At night he had nightmares. There was a resemblance between the two natures, and to possess Lillian was like possessing the mother, which was taboo. Besides, in the nightmare, there was a battle between the two possessions in which he won nothing but a change of masters. Because both his mother and Lillian (in the nightmare they were confused and indistinguishable), instead of living out their own thoughts, occupying their own hands, playing their own instruments, put all their strength, wishes, desires, their wills on him. He felt that in the nightmare they carved him out like a statue, they talked for him, they acted for him, they fought for him, they never let him alone. He was merely the possessed. He was not free.

Lillian, like his mother, was too strong for him. The battle between the two women would be too strong for him. He could not separate them, free himself and make his choice. He was at a disadvantage. So he feared: he feared his mother and the outcries, the scenes, dramas, and he feared Lillian for the same reason since they were of the same elements: fire and water and aggression. So he feared the new invasion which endangered the pale little flame of his life. In the center of his being there was no strength to answer the double challenge. The only alternative was retreat.

When he was six years old he had asked his mother for the secret of how children were born. His mother answered: “I made you.”

“You made me?” Gerard repeated in utter wonder. Then he had stood before a mirror and marveled: “You made this hair? You made this skin?”

“Yes,” said his mother. “I made them.”

“How difficult it must have been, and my nose! And my teeth! And you made me walk, too.” He was lost in admiration of his mother. He believed her. But after a moment of gazing at the mirror he said: “There is one thing I can’t believe. I can’t believe that you made my eyes!”

His eyes. Even today when his mother was still making him, directing him, when she cut his hair, fashioned him, carved him, washed his clothes, what was left free in this encirclement of his being were his eyes. He could not act, but he could see.

But his retreat was inarticulate, negative, baffling to Lillian. When she was hurt, baffled, lost, she in turn retreated, then he renewed his pursuit of her. For he loved her strength and would have liked it for himself. When this strength did not threaten him, when the danger was removed, then he gave way to his attraction for this strength. Then he pursued it. He invited and lured it back, he would not surrender it (to Serge or anyone else). And Lillian who suffered from his retreat suffered even more from his mysterious returns, and his pursuits which ceased as soon as she responded to them.

He was playing with his fascination and his fear.

When she turned her back on him, he renewed his charms, enchanted her and won her back. Feminine wiles used against woman’s strength like women’s ambivalent evasions and returns. Wiles of which Lillian, with her straightforward manly soul, knew nothing.

The obstacle only aroused Lillian’s strength (as it aroused the knights of old) but the obstacle discouraged Gerard and killed his desire. The obstacle became his alibi for weakness. The obstacle for Gerard was insurmountable. As soon as Lillian overcame one, Gerard erected another. By all these diversions and perversions of the truth he preserved from her and from himself the secret of his weakness. The secret was kept. The web of delusion grew around their love. To preserve this fatal secret: you, Lillian, are too strong; you, Gerard, are not strong enough (which would destroy them), Gerard (like a woman) wove false pretexts. The false pretexts did not deceive Lillian. She knew there was a deeper truth but she did not know what it was.

Weary of fighting the false pretexts she turned upon herself, and her own weakness, her self-doubts, suddenly betrayed her. Gerard had awakened the dormant demon doubt. To defend his weakness he had unknowingly struck at her. So Lillian began to think: “I did not arouse his love. I was not beautiful enough.” And she began to make a long list of self-accusations. Then the harm was done. She had been the aggressor so she was the more seriously wounded. Self-doubt asserted itself. The seed of doubt was implanted in Lillian to work its havoc with time. The real Gerard receded, faded, vanished, and was reinstated as a dream image. Other Gerards will appear, until…

After the disappearance of Gerard, Lillian resumed her defensive attitude towards man, and became again the warrior. It became absolutely essential to her to triumph in the smallest issue of an argument. Because she felt so insecure about her own value it became of vital importance to convince and win over everyone to her assertions. So she could not bear to yield, to be convinced, defeated, persuaded, swerved in the little things.

She was now afraid to yield to passion, and because she could not yield to the larger impulses it became essential also to not yield to the small ones, even if her adversary were in the right. She was living on a plane of war. The bigger resistance to the flow of life became one with the smaller resistance to the will of others, and the smallest issue became equal to the ultimate one. The pleasure of yielding on a level of passion being unknown to her, the pleasure of yielding on other levels became equally impossible. She denied herself all the sources of feminine pleasure: of being invaded, of being conquered. In war, conquest was imperative. No approach from the enemy could be interpreted as anything but a threat. She could not see that the real issue of the war was a defense of her being against the invasion of passion. Her enemy was the lover who might possess her. All her intensity was poured into the small battles; to win in the choice of a restaurant, of a movie, of visitors, in opinions, in analysis of people, to win in all the small rivalries through an evening.

At the same time as this urge to triumph continuously, she felt no appeasement or pleasure from her victories. What she won was not what she really wanted. Deep down, what her nature wanted was to be made to yield.

The more she won (and she won often for no man withstood this guerrilla warfare with any honors—he could not see the great importance that a picture hung to the left rather than to the right might have) the more unhappy and empty she felt.

No great catastrophe threatened her. She was not tragically struck down as others were by the death of a loved one at war. There was no visible enemy, no real tragedy, no hospital, no cemetery, no mortuary, no morgue, no criminal court, no crime, no horror. There was nothing.

She was traversing a street. The automobile did not strike her down. It was not she who was inside of the ambulance being delivered to St. Vincent’s Hospital. It was not she whose mother died. It was not she whose brother was killed in the war.

In all the registers of catastrophe her name did not appear. She was not attacked, raped, or mutilated. She was not kidnapped for white slavery.

But as she crossed the street and the wind lifted the dust, just before it touched her face, she felt as if all these horrors had happened to her, she felt the nameless anguish, the shrinking of the heart, the asphyxiation of pain, the horror of torture whose cries no one hears.

Every other sorrow, illness, or pain is understood, pitied, shared with all human beings. Not this one which was mysterious and solitary.

It was ineffectual, inarticulate, unmoving to others as the attempted crying out of the mute.

Everybody understands hunger, illness, poverty, slavery and torture. No one understood that at this moment at which she crossed the street with every privilege granted her, of not being hungry, of not being imprisoned or tortured, all these privileges were a subtler form of torture. They were given to her, the house, the complete family, the food, the loves, like a mirage. Given and denied. They were present to the eyes of others who said: “You are fortunate,” and invisible to her. Because the anguish, the mysterious poison, corroded all of them, distorted the relationships, blighted the food, haunted the house, installed war where there was no apparent war, torture where there was no sign of instruments, and enemies where there were no enemies to capture and defeat.

Anguish was a voiceless woman scre

aming in a nightmare.

She stood waiting for Lillian at the door. And what struck Lillian instantly was the aliveness of Djuna: if only Gerard had been like her! Their meeting was like a joyous encounter of equal forces.

Djuna responded instantly to the quick rhythm, to the intensity. It was a meeting of equal speed, equal fervor, equal strength. It was as if they had been two champion skiers making simultaneous jumps and landing together at the same spot. It was like a meeting of two chemicals exactly balanced, fusing and foaming with the pleasure of achieved proportions.

Lillian knew that Djuna would not sit peacefully or passively in her room awaiting the knock on her door, perhaps not hearing it the first time, or hearing it and walking casually towards it. She knew Djuna would have her door open and would be there when the elevator deposited hr. And Djuna knew by the swift approach of Lillian that Lillian would have the answer to her alert curiosity, to her impatience; that she would hasten the elevator trip, quicken the journey, slide over the heavy carpet in time to meet this wave of impatience and enthusiasm.

Just as there are elements which are sensitive to change and climate and rise fast to higher temperatures, there were in Lillian and Djuna rhythms which left them both suspended in utter solitude. It was not in body alone that they arrived on time for their meetings, but they arrived primed for high living, primed for flight, for explosion, for ecstasy, for feeling, for all experience. The slowness of others in starting, their slowness in answering, caused them often to soar alone.

To Djuna Lillian answered almost before she spoke, answered with her bristling hair and fluttering hands, and the tinkle of her jewelry.

“Gerard lost everything when he lost you,” said Djuna before Lillian had taken off her coat. “He lost life.”

Lillian was trying to recapture an impression she had before seeing Djuna. “Why, Djuna, when I heard your voice over the telephone I thought you were delicate and fragile. And you look fragile but somehow not weak. I came to…well, to protect you. I don’t know what from.”

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

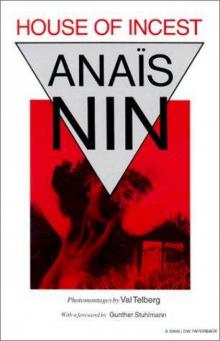

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest