Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 Read online

The Diary Of Anaïs Nin

VOLUME FOUR 1944–1947

Edited and with a Preface by Gunther Stuhlmann

* * *

A Harvest/HBJ Book

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich

New York and London

* * *

Copyright © 1971 by Anais Nin

Preface copyright © 1971 by Gunther Stuhlmann

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be

reproduced or transmitted in any form or by

any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording,

or any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the

work should be mailed to: Copyrights and Permissions Department,

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, Orlando, Florida 32887.

Library of Congress

Catalog Card Number: 66-12917

ISBN 0-15-626028-x

Printed in the United States of America

I J K L M

* * *

Preface

The publication, during the past five years, of three volumes drawn from the monumental Diary of Anaïs Nin, which she has kept now for half a century, has brought to the author a cornucopia of critical acclaim. It has established Miss Nin's life work, in the words of one critic, as "one of the most remarkable diaries in the history of letters."

This intensely personal document also seems to have assumed a special individual significance for many contemporary readers, which goes beyond the genuine literary, historical, and biographical value of the Diary. Transcending the borders of age and background, its spectrum of recorded experience, thought, and emotion seems to invite direct identification, a sense of recognition, a sharing of concerns. In the numerous personal letters addressed to Miss Nin one note is struck again and again: "Yes, this is exactly the way I have felt, myself; these are the very things I am struggling with now." Many readers, especially among the young, have responded to the Diary with an intensity, an open directness, reminiscent of the voluble emotions released by Miss Nin almost four decades ago in the "Hotel Chaotica" in New York. Indeed, this very personal response to the Diary seems to bear out Miss Nin's assumption—quoted in the preface to Volume II—that "the personal life deeply lived always expands into truths beyond itself."

The specifics, the special circumstances of Miss Nin's own exploration of the "inner spaces" of the self, lucidly presented, sharply observed, open themselves to sharing: her uncertain childhood as a European "exile" in New York; the long struggle to free herself from the domineering shadow of her father; the lifelong effort to create for herself and her friends a nourishing, "livable" environment in a troubled, hostile, or indifferent world; her attempts to gain a totality of experience, a "personal relation to all things and people"; and her constant striving to capture an intuitive rather than ideological "feminine consciousness" in both her life and her art. The personal, the singular, expands under the prism of the Diary to become, in Miss Nin's words, "universal, mythical, symbolic." ("The hero of this book," she notes in these pages, "is the malady which makes our lives a drama of compulsion instead of freedom.")

The preceding three volumes, extracted from the broad flow of the original Diary manuscripts, are essentially self-contained units. Each forms, as it were, a complete "chapter" in the "book" of Anais Nin's life. Each volume marks a stage in Miss Nin's development. Each moves from a particular starting point toward change, greater awareness, new beginnings. At the core of each volume is exploration, unfolding, growth.

Volume I opened in Louvecicnnes, near Paris, when, in 193‹, Miss Nin first appeared in print with a deeply felt appreciation of D. H. Lawrence, who had been quietly buried in Vence only a year earlier. This publication—through a chain of circumstances pinpointed only by hindsight—led to her contact with the unknown expatriate Henry Miller, to the "mad" Antonin Artaud, to psychoanalysts Dr. René Allendy and Dr. Otto Rank, to her own discovery of the turmoils and possibilities of psychoanalysis. Volume II (1934-1939) saw Miss Nin in New York, caught between the demands of analysis and her need to write, opting for the latter, returning to her "romantic life" in France only to be forced, by the outbreak of World War II, to leave again, to part from a pattern of life she knew she "would never see again." Volume III (1939-1914) mirrored her second "exile" in New York—paralleling, emotionally, much of her childhood experience (which gave the initial impetus to the Diary itself) as a reluctant refugee in Manhattan—and her efforts to establish herself as a "foreign" writer on these shores.

The present volume continues the chronology. It links up with her first "breakthrough" here as a writer, early in 1944, following the publication of a handset edition of her stories, Under a Glass Bell, and a review by Edmund Wilson in the New Yorker. It is based on the original manuscript volumes sixty-eight to seventy-four. Miss Nin and the editor have followed the same principles of selection established in the previous volumes. The bracketed dates have been supplied by the editor. The omission of some characters was again necessary, and a few names have been changed and are indicated as pseudonyms in the index.

The basic themes of the Diary—self, femininity, neurosis, freedom, relationships, the confluence of art and life—also provide the essential strands in the tapestry of this volume. Again, there is often a "prophetic" quality to Miss Nin's endeavors and responses. Her antennae detect and register, as the radar of true artists has done through the centuries, much that was only dimly perceived at the time. Much of what she felt and sensed about vital aspects of life in America during the 1940s foreshadowed, in its implications, many of the strong concerns voiced only recently on a larger scale by the revolutionary young, by the advocates of a "new consciousness."

In this country, among the people who fielded the giant armada that defeated Hitler's Germany, that atom-blasted Japan into surrender, she perceived, amidst all the power and technology, a curious emptiness. "The drama of our present life," she writes, is that there is "nothing big enough, deep enough, strong enough." America's most active contribution to the formation of character, she notes, is the development of an impermeable shell behind which to hide. "A tough hide. Grow it early."

Most of the men she meets are "plain, one-dimensional." She deplores their single-mindedness, their lack of color. They are "prosaic down-to-earth, always talking of politics, never for one moment in the world of music and pleasure, never free of the weight of the daily problems, never joyous, never elated, made of either concrete and steel or like workhorses, indifferent to their bodies, obsessed with power."

She misses meaningful personal relationships. "Every friend I reach out here to seems incapable of big friendship." The depersonalization of relationships alarms her. "My friendships, instead of being concentrated on a very few, as in Paris, have become fragmented into many. I find only partial relationships."

"I am aware," she writes, "that what I love and seek is illusive, tricky.... What ought to be and not what is interests me....In between, an all-consuming loneliness."

Miss Nin's continuing refuge still is the world of the young, the undiscovered, the potential realizers of "what ought to be." "When I am with mature people," she confesses, "I feel their rigidities, their tight crystallizations." She is tossed back, emotionally, into the strictured atmosphere of the Spanish father. "With the young," on the contrary, "one lives in the future. I prefer that." Perhaps by identifying with the young ("I feel as they do, I think and act as they do"), by being "open," and not yet "finite," she herself can escape finality, she can s

tay fluid, mercurial.

She has retreated from the "children" she used to mother in the past—Henry Miller, Gonzalo—perhaps because with aging they themselves have lost some of their fluidity, have become set, finite, predictable.

By repudiating what appeared to her stifling maturity, by escaping from the finalities of the "real world" into the free-form realm of the artist, into the self-centered emporium of the child-adult ("Both live in a world of their own making"), Miss Nin could stave off the "outside world" for a while. But caught in a culture which saw the artist either as a swaggering, hard-drinking he-man or draped in effeminate exclusiveness, even the sensitive young extracted a price ("I disguised the woman in myself to be allowed to re-enter the world of the poet, the dreamer, the child") she could not continue to pay. "I create a myth and a legend, a lie, a fairy tale, a magical world, and one that collapses every day and makes me feel like going the way of Virginia Woolf."

For the artist, who is not merely a technician or a propagandist, the American climate does not seem very propitious ("Much writing in America has confused banality with simplicity, and the cliché with universal sincerity"), the emphasis on competition, on "bigger and better," exaggerated.

"My greatest problem here," Miss Nin writes, "in a polemic-loving America, is my dislike of polemics, of belligerence, of battle. Even intellectually, I do not like wrestling matches. I do not like talk marathons, I do not like arguments, or struggles to convert others. I seek harmony. If it is not there, I move away."

At a time when there is much talk about reordering of priorities, Miss Nin's question, asked a quarter of a century ago, seems especially pertinent: "Why does everyone here believe that by all of us thinking of nothing else but the mechanics of living, of history, we will solve all problems?" And she adds: "I don't think the American obsession with politics and economics has improved anything."

The reordering of priorities, as Miss Nin has so often remarked, must begin in "inner space," before America, before anyone, can ever be re-formed. Her own struggle, in this volume, is far from won. ("I have tried not to be neurotic, not romantic, not destructive, but I may be all of these in disguises." And: "While neurosis rules, all life becomes a symbolic play. This is the story I am trying to tell.... The story of complete freedom does not appear yet in this volume.") But again she draws from her own experience of our growing encapsulation, our lack of contact "now that we have reached a hastier and more superficial rhythm, now that we believe we are in touch with a greater amount of people, more people, more countries. This is the illusion which might cheat us of being in touch deeply with the one breathing next to us. The dangerous time when mechanical voices, radios, telephones, take the place of human intimacies, and the concept of being in touch with millions brings a greater and greater poverty in intimacy and human vision."

With instant replay and total electronic communications on hand, these lines from Miss Nin's Diary, written so long ago by today's standards, have perhaps never been more "up-to-date," more pertinent.

New York

April, 1971

GUNTHER STUHLMANN

[April, 1944]

The first edition of Under a Glass Bell sold out in three weeks and I have to make plans for a reprinting.

As Gonzalo wanted the press to seem more businesslike, more impersonal, less like a private press run by writers, we had to find an appropriate place. The Villager had just moved out of 17 East Thirteenth Street. It was a small, two-story house. The ground level with a cement floor was suitable for the printing press. A narrow, curved iron staircase led to the second floor, which would be perfect for the engraving press. The house rented for sixty-five dollars a month, almost twice as much as the old studio on Macdougal Street. But Gonzalo hoped it would bring him more work.

The small house was painted green. There was a large front window, big enough for displays, and it could be fixed to exhibit our beautiful books.

Next door was a coffee shop for workmen. Across the way, Schrafft's (if prospective customers wished to take us to lunch).

The press is now named "Gemor Press," after Gonzalo's initials. William Hayter arrived with a printing job. Gonzalo's friends dropped in with work.

Gonzalo is active, joyous, transformed. It is his press. His pleasure gave me pleasure. He began to get up early. He kept his appointments. I could take time off to write. But for the moment, we both have to work on a second printing of Under a Glass Bell. The first edition of three hundred copies was sold quickly. A publisher who met me at a party said: "How did you get so well known with three hundred copies of a book?"

Installing the press was a tremendous labor. Work with electricians, window cleaners, movers; packing and unpacking; transferring trays of type into type cases, counting paper, beginning to work on engravings. The second edition will have only nine engravings instead of seventeen. It will be linotyped instead of hand-set, and will cost three dollars instead of five. We unpacked twelve boxes of paper, books, plates, tools, etc. We bought wastebaskets, scrapbooks, bulbs, blotters, files. We pasted samples of Gonzalo's work into a scrapbook, to show his ability as a designer of books.

It was all done in a week.

Gonzalo has assumed leadership. He is proud of his place, his machine, his independence. I am very tired, but content. I am proud of my human creation.

Took one thousand prints out from between blotters. Cut paper. Exhaustion. Contentment.

Intense labor.

Deep down I feel an understanding of those who revolt against the slavery of work, but I have also seen those who rebelled against the system harm themselves beyond repair.

I watch Gonzalo taking pride in his work. The guilt which often accompanies those who do not work, who do not create anything, can be more terrible and destructive than the discipline and sacrifice of work and creation.

Is Gonzalo now free of the guilt which oppressed him and poisoned his leisure? He is no longer tortured by insomnia. He does not feel ashamed or humiliated before his friends. (One is a Spanish doctor who fought in the Civil War, the other a Frenchman who teaches mathematics at N. Y. U.) The editor of a South American magazine comes to see him.

He feels his power, has discovered his skills and gifts. At the same time, it is like watching a child lose his gaiety and innocence as he matures and assumes responsibility. Gonzalo paid dearly for his illusions of freedom. Henry [Miller]'s letters to me are burdened with guilt, talk of atonement. Even Henry, who always said he felt free of any feeling of gratitude or indebtedness. Even my father, who considered himself a freethinker, a man who did not believe in religion and therefore in guilt, allowed himself during his last days in Paris to resemble a breast-beating, atoning, religious maniac.

I watch Gonzalo work and a part of me is sad that he is not free to enjoy, for both Gonzalo and Henry had an endless capacity for enjoyment. This was the secret of my acceptance of what seemed to others an exploitation of me.

Letter from Henry:

I had already seen the [Edmund] Wilson review*—several people sent me the clippings. It was well intentioned but inept and inadequate, wasn't it? I was furious, myself. So that did the trick! It's all so bloody spurious, what makes success here. The other night, after reading proofs of my new book with [James] Laughlin (Sunday After the War) because I had included in this book more pages about you, the diary, etc. (things you know) I went back to my essay "Une Être Étoilique"** and reread it. I had tears in my eyes. It is perhaps the best bit of writing I ever did. Even if no one person can possibly put in words all that may be said about the diary I feel that I made a very wonderful attempt, elliptically. (And how strange that George Orwell, the English writer, should have used my phrase "inside the whale" for his left-handed attack upon me!) I am thinking all the time only about how to get the diary launched. I have suggested it whenever and wherever possible....

I must tell you that I am trying to raise a good sum of money—to live quietly for a year and finish what work I have on hand. I ha

ve had to waste a good deal of time these past two years to keep going. It doesn't bother me or hurt me—but it's a sheer waste. I am already receiving promises and half-promises of substantial aid. I think eventually I shall get much more than I asked for. In which case I shall be able to send you a substantial sum. And as I told you once, should you not want to bring out the diary yet, should you need the money for other purposes, why make what use of it you wish. I merely thought that the diary, the publishing of it, would be the best gift I could make you. It wouldn't even be a gift, because I am still digesting, assimilating, benefitting from all the tremendous gifts you made me....

I still feel it is too bad that, with your enormous and truly "legendary" reputation, only glimpses of your great gift are seen. I urge you with all my heart to concentrate on the diary. The world will be bowled over when the real manifestation of your spirit begins, believe me. As I said before, rereading my own words about you I was so stirred that I was beside myself. It must be maddening to you. It is to me. How can they wait and wait and wait? I said to myself. And the more maddening because to help me, your own work has been neglected. But nobody wants more than I to redeem himself....

I am living with nature more and more, and this Big Sur country (where I have been now for two months) is truly tremendous. There are only about twenty-five people on this mail route. Back from the coast over the mountains, there is an absolute emptiness. It is almost as forbidding as Tibet, and it fascinates me. I should like to go back in there and live for a time quite alone. But I would need a horse, and an axe and a few other things I have never used. I am a little terrified of it.

The other day I was offered a little house on a mountain—quite isolated—difficult to get to on foot (and I have only my feet to use) but I am taking it. I move in next week. My address remains the same. I shall have a taste of real solitude. Certainly I miss everything else—terribly. But I consider myself fortunate. And I am more and more at peace with myself....

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

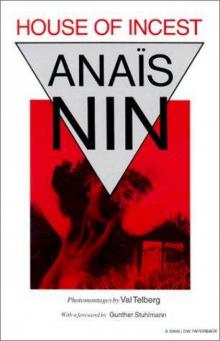

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest