The Winter of Artifice Read online

The Winter of Artifice

Anaïs Nin

Derived from The Winter of Artifice: a facsimile of the original 1939 Paris edition

© 2007 Sky Blue Press

To Nancy and Larry

with love.

INTRODUCTION

From the publication of her first book in 1932 until the mid 1960s, Anaïs Nin was an obscure author who published books with, often, small presses, and short fiction in little magazines. With the appearance of The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1931-1934 (1966), however, she became well known, and then increasingly popular as more volumes of her diary were published. The number of her books published since her death in 1977 confirms that her appeal continues. At least twenty books of new or mostly new material have been published as of late 2006. These include nine volumes of her diary, four of them identified as unexpurgated (these four contain some previously published material); three volumes of correspondence (with Henry Miller, David Pepperell, and Felix Pollak); two volumes of erotica, plus five books of selections from them, one illustrated with photographs and another with artwork; and a collection of stories. Another volume of erotica has been attributed to her and her friends on the basis of unconvincing evidence. Additionally, some short pieces and selections from works published during Nin’s lifetime have been collected and published as books, and one novella has been published under its own title. Such a substantial number of posthumous publications begs the question of whether worthwhile Nin writing remains unavailable. Indeed so. Nin’s third book and second volume of fiction, The Winter of Artifice, has not been republished since its initial appearance in 1939. At least one serious reader considers this collection of three novellas Nin’s major fictional accomplishment. Writing to Nin in 1960, Felix Pollak states, “I stillink it is your best book, that unexpurgated version — magic, entrancing piece of writing” (Nin and Pollak 1998, 152). His assessment is debatable, though reasons for the significance of the book are not arguable: the novellas present several key characters dealing with emotional issues (a central focus in Nin’s fiction generally), they serve to illustrate Henry Miller’s influence on Nin’s prose, they indicate how Nin used diary material in her fiction, and theyprovide a basis for examining Nin as evaluator and reviser of her work.

“Djuna,” “Lilith,” and “The Voice” were all published for the first time in The Winter of Artifice. “Djuna” has never been republished in its entirety; the other novellas appear in every edition of Winter of Artifice, as Nin later named the collection, though she revised them after their 1939 publication and changed the title of one of them.

Set in Paris, “Djuna” concerns Djuna’s involvement with Hans and Johanna, a couple married unhappily. Djuna, the narrator, is a writer attracted to impoverished Hans because she considers him highly intelligent and admires the manuscript he struggles to complete. His novel depicts a character inspired by Johanna, who objects to his harsh portrayal of her. Although Djuna and Hans are lovers, she views herself primarily as the nurturer of his talent, an aspect of Hans that Johanna does not value. When Johanna returns to Paris after having been away for the first two-thirds of the narrative, she and Djuna develop a closeness that becomes physical to the degree that they kiss and fondle. The night they spend together in bed concludes the novella.

Despite the drama surrounding Djuna, Hans, and Johanna, including the tension between the spouses, the novella mainly deals with the narrator’s quest for contentment. Although Djuna does not identify her problems, she acknowledges some of her deficiencies: lying to Hans so he will not think her ordinary, assuming any role in order to accommodate him, and wanting to be loved while remaining ultimately unknown.

Johanna appeals to Djuna because Hans’s wife possesses traits that Djuna lacks, needs, and desires. These include forthrightness and the ability to act decisively. Even though the two women are attracted to each other and, taken together, constitute a complete person, Johanna does not satisfy Djuna. Why? Because in loving Johanna, Djuna embraces “the desired, unrealized, unformulated half of” herself. In order to gain emotional equilibrium, Djuna must unite with her true opposite, a man, as she implies after characterizing her love for Johanna as self-love, as narcissism: “What I loved to-day [herself in Johanna], far, far above this self, was Hans. Hans, the other ” (Nin 1939, 85).

The novella concludes without resolution. Johanna plans to leave Hans for another man. If she does, Djuna will presumably have unrestricted access to Hans. A life with him might help solve her problems. Yet if Johanna does not leave Hans, Djuna must decide whether to continue her involvement with him on a less-than-ideal basis — by sharing him with Johanna — or leave him, hoping to find someone to satisfy her needs.

The second novella, “Lilith,” focuses on the narrator, Lilith, and her problems that result from her father’s abandonment of the family two decades earlier, when she was ten years old. The reunion of the daughter (a writer) and her unnamed father (a musician) in France is the occasion of Lilith’s narrative, although the text does not indicate what inspired their meeting.

Any child could be expected to interpret the permanent absence of a parent as rejection, especially after the parent treated the child insensitively when the family was intact, as happened with Lilith. Her father terrified her; he thought her ugly. His absence affected her to the degree that her life has been lonely, that she has been incapable of appreciating joyous moments, and that she has acted against her own best interest. As a way of retaliating against her demanding, perfectionist father, the adult Lilith violated their shared tastes and preferences in order to offend him. She did this by, among other things, loving only poor men, seeking ugliness, and courting danger. The effects of such actions on her are unknown.

Despite her father’s unfeeling treatment of her, the mature Lilith knows that her father acted as he did because of his own problems. She realizes that he was an inadequate parent partly because he lost faith in love after being betrayed by his betrothed, who is not identified. She also comprehends that what she perceived as his abandonment was an attempt to save himself from an untenable marriage by fleeing it. As a result of these awarenesses, Lilith forgives his fatherly shortcomings.

Understanding her father’s actions does not mean that Lilith should grant his every wish, however. Because of the effects of his father’s favoring of a daughter over him during his own childhood, Lilith’s father has been jealous of Lilith’s life independent of him. Within this context, he thinks that, in a sense, his daughter has abandoned him. Partly to protect himself against the pain that this perception causes, he implies that she should devote herself to him. His desire is unreasonable. If she commits to him, disaster would result not only because she would lack significant interaction with other people, but also because father and daughter are too similar. As Djuna learns in the first novella, Lilith knows that one must unite with one’s opposite, or at least with someone significantly different from oneself. Wisely, she does not dedicate herself to her father.

Although Lilith understands and forgives her father, she discovers that she no longer loves him. She likens the demise of her love to the death of her fetus, at a time unspecified. As it was dead, “the little girl in me was dead too. The woman had been saved. And with the little girl died the need of a father” (Nin 1939, 197). Lilith has liberated herself from the oppressive influence of her father and gained a healthy sense of her own individuality and independence. As a result, she will presumably lead a more fulfilling life than previously.

“The Voice,” the last novella, concerns an analyst who treats his patients conscientiously and sometimes effectively. These include Lillian, a violinist who thinks herself a lesbian; Mischa, a cellist with a stiff hand and a bad leg; and Geor

gia, an orchestra conductor who feels uncomfortable with her womanhood because of her father’s amorous adventures when she was young. Most importantly, the Voice treats Djuna and Lilith, the narrators of the first two novellas. All these characters, including the Voice, have significant emotional problems.

FY” height=”0” width=”24” “ The Voice” does not answer the question implied at the conclusion of “Djuna”: will Johanna leave Hans? Whatever Johanna’s decision, in “The Voice” Djuna and Hans remain together in some manner, though this is a minor issue. Her frustrated desire to deal with people on the deepest level, her fear of the past, and her avoidance of reality by living in a dream inspire Djuna to seek help from the Voice. By the end of the novella, he has helped her understand some of her problems, though she continues living too much in a dream.

Lilith has sexual relations with at least one woman and many men, not including her husband; proudly strong and independent, she is really weak and dependent. She believes she loves the Voice; like Djuna, she fears reality. Lilith reinforces the conclusion of the second novella by telling the Voice that her “need of a father is over” (Nin 1939, 238). Yet for her the Voice functions as a father figure, indicating her continuing need for the guidance and emotional fulfillment that a father can offer. “The Voice” ends with Lilith and her analyst vacationing together. Although their outing is unsuccessful and she spurns him because he repulses her, perhaps her rejection of him is positive: she possibly no longer needs a man such as the Voice or her father. If through professional or personal interaction the Voice helps Lilith overcome the need for a father, including himself, he serves her well.

As Lilith is something other than what she seems at the beginning of the novella, so is the Voice different from how he appears. Professionally confident and authoritative, he needs as much help as his patients. He understands and assists them, but not himself. His treatment of Djuna, Lilith, and others — he is deeply involved with but ultimately detached from them — parallels and reinforces his problem generally: lack of a serious human relationship, or love. The genuine love of anybody would save him from isolation. Yet because the love some patients profess for him is really attachment to his position and expertise, not to the man himself, he remains separated from life.

Need for love affects the Voice professionally. During a session with him, Lilith bares her breasts, which she thinks too small, ostensibly so he will assure her that they are normal. He responds by blushing and by cupping his hand, as if to hold one of her breasts. As he demonstrates feeling, he loses professional control. Lilith, who assumes the analyst’s chair while the Voice reclines on the patient’s couch, notes that he is unhappy and encourages him to explain why. Temporarily relinquishing his professional role and attempting to express his true feelings suggest that soon he might begin addressing his problems seriously.

Lilith grants the Voice’s request to accompany her to a beach because she thinks she loves her analyst, though Djuna correctly terms Lilith’s feelings for him a mirage. Unfortunately for him, his quest for a human connection is frustrated because Lilith realizes that she does not love him: “He remained nothing but the Voice with a death-like breath” (Nin 1939, 289). Although the novella ends before Lilith tells him her true feelings, surely she will reveal them. If so, how will her announcement affect him, this emotionally stunted, middle-aged man who thinks that Lilith is bringing him to life? In all likelihood, the pain of Lilith’s rejection will be great, possibly causing him never again to open himself to someone. He will likely remain an anonymous voice, valued and admired by his patients, though unloved. Only treatment by an analyst would seem to offer him hope for what might becalled normalcy.

After moving to New York in late 1939, following the publication of The Winter of Artifice, Nin established a press to publish her books (and books by others) because she could not interest American publishers in her work. The initial project of her press was, in 1942, a revised edition of her most recently published book, the collection of novellas.

Nin might first have published Winter of Artifice because the 1939 edition was, apparently, almost stillborn. Surely few people read it, either in France or the United States. For one reason, only a small number of copies of The Winter of Artifice were available, partly because the print run was doubtless modest; for another, Nin had little reputation, so her name would have attracted few buyers; for yet another, the book received, according to Nin, “no distribution[,] no reviews” (Nin 1969, 259), possibly because the series of which it was a part had as its goal, according to Henry Miller’s biographer Jay Martin, “the publication of books for which no commercial audience existed” (Martin 1978, 330). Additionally, Jack Kahane, owner of the Obelisk Press, which published Nin’s book, died in early September 1939, making the fate of the copies of The Winter of Artifice problematic. Further, as Gunther Stuhlmann notes in the introduction to The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1939-1944, the book “disappear[ed] in the turmoil of war” (Nin 1969, ix). Nin was unable to take books with her to New York. Even had she taken copies of her new book, they might have been denied entry into the United States because they were, according to her, censored there (13); had she mailed them, they might have been seized because they were, according to Nin, “banned by the U.S.A. mails” (Nin and Pollak 1998, 7). She states that a limited number of copies were available in the United States (they “escaped censorship”) and that they sold well, but she does not identify the vendors (Nin 1969, 13). In 1954, though, her correspondent Felix Pollak engaged “book finding services” to locate a copy; they failed (Nin and Pollak 1998, 16). Summarizing realities that influenced the reception of her book, Nin writes, in a diary entry dated 17 October 1939, “My beautiful Winter of Artifice, dressed in an ardent blue, somber, like the priests of Saturn in ancient Egypt, with the design of the obelisk on an Atlantean sky, stifled by the war, and Kahane’s death” (Nin 1996, 370).

If the scarcity of The Winter of Artifice was a reason why Nin made Winter of Artifice the first publication of her press, it was neither the only reason nor the major one. Unhappy with the contents of the Paris edition, she wished to publish a revised text that reflected her current thinking about it. The 1939 version of the novellas contains plot and narrative irregularities. In “Djuna,” for example, the narrator fails to specify whether she, Djuna, lives with Hans during Johanna’s absence — and if not, why not? — and does not explain why Johanna, upon returning to Paris, spends her first night in a hotel rather than with Hans, her husband. In “Lilith,” how does the daughter harm her father, as noted on page 128? Why does Lilith retaliate against her father by acting against her own best interest when, because of their long separation, he apparently does not know what she is doing? Further, why does narration in “The Voice” shift from third person to first on pages 278-79? Was Nin writing what became known as postmodern fiction, in the sense of intentionally omitting elements of plot and presenting an inconsistent point of view? If not, such shortcomings grate. She resolved some of the problems when revising the contents for publication in 1942.

Despite these issues, Nin seemed most dissatisfied with the 1939 text because it does not fully represent her own writing. She explains this concern to Felix Pollak: “When I wrote this book I was too much under the influence of Henry Miller’s writing and his revisions of my work (I was just beginning to write)” (Nin and Pollak 1998, 7).

Anyone wishing to understand how extensively Miller edited Nin’s writing of The Winter of Artifice could do so by examining his comments on two facsimile typescript pages of “Djuna” published in Anais: An International Journal (Harms 1986, 114-15). The revised version of these pages appears on pages 54-55 in the 1939 edition. Miller takes seriously his task of improving Nin’s prose, which Nin acknowledges was then weak because French, not English, was her original language (Nin 1987, 93). In concentrating on style, idiom, and diction, he forces her to address aspects of writing that did not particularly trouble her when writing in her diary, the written sour

ce of the characters and events in “Djuna.” He addresses the issue directly: “Take out all the inflation and leave the hard, bare rock of concrete reality — then you get accurate poignancy. I am laying it on thick, because now you should see how certain aspects of ‘diary’ writing lead to falseaccents. Because it is a writing behind walls — without hope of criticism or of suffering the strong light of day. Getme?” (Harms 1986, 115)

Comparing a typescript paragraph with its published version indicates the care Miller took with and the degree to which he influenced Nin’s writing. The draft version reads as follows:

There was tacked on Rab’s door a paper with his name and address carfeully printed. She asked him: Are you afarid to forget your name and who you are,and where you live? Have you not played with the idea of amnesia, which only meens a somanabulistic condition of the ideal self. The conscince goes to sleep and then the critical self too, and you can walk the streets and act as you please without calms. Its only our name, our address, and our relations which bother us, like so many memorandums of what we ought to be to correspond to their image of us. But the important thing is only to resemble our own image of ourselves. (Harms 1986, 114)

Miller corrects spacing problems and misspellings. He also comments on some of his substantive alterations and suggestions. For example, about in’s construction “which only means,” he states, “Bad expression ‘which is simply another way of saying, etc.’ But it needs a better transition.” Writing about Nin’s use of “calms” for “qualms,” he barks, “Look it up!!!” Regarding “memorandums,” he notes that the “plural of Latin words ending in ‘um’ is ‘a’.” Responding to the conclusion of Nin’s penultimate sentence, he comments, “Bad sentence structure.” At the end of the paragraph, he advises, “Watch all your ands, buts etc. Weakly used!”

Here is the published version of this paragraph.

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

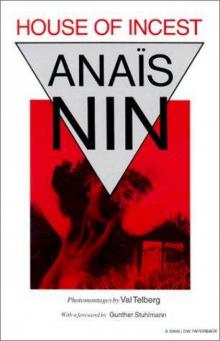

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest