Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 Read online

The Diary Of Anaïs Nin

VOLUME FIVE 1947-1955

Edited and with a Preface by Gunther Stuhlmann

* * *

HBJ

A Harvest/HBJ Book

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers

San Diego New York London

* * *

Copyright © 1974 by Anaïs Nin

Preface copyright © 1974 by Gunther Stuhlmann

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be

reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording,

or any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of

any part of the work should be mailed to:

Copyrights and Permissions Department,

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers,

Orlando, Florida 32887.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data (Revised)

Nin, Anaïs, 1903-1977.

The diary of Anaïs Nin.

(A Harvest/HBJ book)

CONTENTS: [1] 1931-1934.—[2] 1934-1939. [5]

1947-1955.

1. Nin, Anaïs, 1903–1977—Biography.

I. Stuhlmann, Gunther, ed. II. Title.

PS3527.I865Z5 1969 818'.5'203 77-2085

ISBN 0-15-626030-1

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvest edition 1975

E F G H I J

* * *

Preface

With the publication of this fifth volume drawn from the original diaries of Anaïs Nin we are gaining an ever larger view of this unique and massive literary undertaking. Each one of the published volumes—self-contained yet contiguous—exposed a fresh segment, a new chapter in this ongoing "novel" of a remarkable life. We saw Anaïs Nin emerge in Paris as a writer and catalyst to Henry Miller, Antonin Artaud, Dr. Otto Rank, and many others (1931–34); we followed her on a vibrant mission to the New World where her pursuit of psychoanalysis conflicted with her survival as a writer (1934–39); we watched the end of her "romantic life" in Europe and her reluctant return to the United States (1939–44); and we observed her efforts to come to terms with her second exile in America (1944–47). Each publication brought to light another portion of that grand store of varicolored, multishaped, multisized notebooks which, by 1947, amounted to some seventy-five handwritten volumes, a body of work that for years had defied all efforts at publication.

The present volume, drawn from the original diaries seventy-five to eighty-eight, and covering some eight years, to 1955, extends our total view of the Diary to a period of almost twenty-five years. From this vantage point we can discern the longer lines of growth and development. We can spot more easily the recurring themes—conflicts, conditioned responses, emotional patterns, the lifelong efforts to shake off the past, to create a "livable" present—that make up the essential warp and woof of Anaïs Nin's luminous tapestry. Beyond the individual event, the biographical fact, the nascent portrait, the captured high moment, the meditations and working notes, emerge deeper motivations, stronger connections. Indeed, the availability of all this material now may also explain the recent emergence of the first comprehensive critical studies of the published Diary.*

The changes in tone and in the very function of the Diary, seen over a stretch of time, also seem more noticeable. What started out as an enticing "letter," a Scheherazade, to bring back the lost father, had turned in the 1930s into Anaïs Nin's "kief, hashish, and opium pipe," and, by 1955, was evolving into an ever more consciously applied artistic instrument: "I have settled down to fill out, round out the diary.... I write about the developments and conclusions which took place twenty years later. It all falls into place."

But the essentia] need for the Diary, the tenacious, often joyous interplay between the Diary and its creator, which survived all moments of peril, remains. ("When I don't write I feel my world shrinking, I feel I am in a prison.") The urge to preserve is as strong as ever. ("The diary gave me a frightening mistrust of memory. Memory is a great betrayer. Whenever I read it, I find it different from the way I remembered the scenes and the talk.") The intensity of her struggle to resolve persistent problems, to shake off neurosis, to gain a firm hold on the "secret of personal freedom," which is a secret of creation, still reverberates through these pages.

Her enthusiastic response to new-found color and beauty in Mexico ("I felt a new woman would be born there") and her retreat from the arid frenzies of New York City to rustic serenity in California still do not resolve the conflict between repose(withdrawal?) and activity(succumbing to the outside world?). "This year," she writes, late in 1950, "the diary almost expired from too much traveling, too much moving about, too many changes. I felt pulled outward into activity, I did not want to meditate and examine...." Using the two symbolic poles of New York and California, she feels "there must be a third way of life which I have to create myself."

The present, to her, is still unbearable at times. "I feel suffocated in my life," Anaïs Nin confides to her new psychiatrist in 1952, "overwhelmed by the demands put on me." The past still beckons as the paradise lost: "When I imagine the kind of life I like best, it was my bohemian life on the houseboat in Paris." But she also recognizes the past overshadowed by the father's critical eye, by the emotional camera lens that forever seemed to dog her steps. "That eye had to be exercised, or else, like that of a demanding god, pleased. I had to labor at presenting a pleasing image." The shedding of disguises is at the core of growing, and she knows that it takes courage "to be myself, rather than disguise myself." There is, after all, an Anaïs "who could love an ordinary tree which was neither symbolic, nor exotic, nor rare, nor historic, nor unique."

In a letter to Maxwell Geismar, in 1955, she measures her own progress ("I don't live here any more, I live in the future") toward that undisguised Anaïs:

This year I finally achieved objectivity, very difficult for a romantic. The divorce from America, as I call it, was painful, but has proved very creative and liberating. It was like breaking with a crabby, puritanical, restrictive and punitive parent. As soon as I overcame the hurt, I began to write better than ever. America, for me personally, has been oppressive and destructive. But today I am completely free of it. I don't need to go to France, or anywhere. I don't need to be published. I only need to continue my personal life, so beautiful and in full bloom, and to do my major work, which is the diary. I merely forgot for a few years what I had set out to do.

The Diary, we all know now, is indeed Anaïs Nin's major work. When she took up her pen on that first miserable journey into exile, at the age of eleven, she tried, by the sheer magic of her words, to bring back a golden past. She tried to lasso that universal dream of a father who will hold us safe from the realities of the world, from loss, separation, indifference, from the pain of growing up and dying and forgetting. She has never given up trying. Trusting forever in the magic of the word ("The role of the writer is not to say what we can all say but what we are unable to say"), she created, in the Diary, an instrument that shaped the very contours of her own life.

In answer to the question"Why does one write?"Anaïs Nin once replied: "... It is a world for others, an inheritance for others ... in the end. When you make a world tolerable for yourself you make a world tolerable for others."

GUNTHER STUHLMANN

New York, N.Y.

November, 1973

[Winter, 1947–1948]

Acapulco, Mexico.

I am lying on a hammock, on t

he terrace of my room at the Hotel Mirador, the diary open on my knees, the sun shining on the diary, and I have no desire to write. The sun, the leaves, the shade, the warmth, are so alive that they lull the senses, calm the imagination. This is perfection. There is no need to portray, to preserve. It is eternal, it overwhelms you, it is complete.

The natives have not yet learned from the white man his inventions for traveling away from the present, his scientific capacity for analyzing warmth into a chemical substance, for abstracting human beings into symbols. The white man has invented glasses which make objects too near or too far, cameras, telescopes, spyglasses, objects which put glass between living and vision. It is the image he seeks to possess, not the texture, the living warmth, the human closeness.

Here in Mexico they see only the present. This communion of eyes and smiles is elating. In New York people seem intent on not seeing each other. Only children look with such unashamed curiosity. Poor white man, wandering and lost in his proud possession of a dimension in which bodies become invisible to the naked eye, as if staring were an immodest act. Here I feel incarnated and in full possession of my own body.

A new territory of pleasure. The green of the foliage is not like any other green; it is deeper, lacquered and moist. The leaves are heavier and fuller, the flowers bigger. They seem surcharged with sap, and more alive, as if they never have to close against the frost, or even a cold night. As if they have no need of sleep.

At the beach a child came forward from a group of children, carrying a small boat made of shells. She wanted me to buy it. She was small for her age, delicately molded like a miniature child, as Mexican children often are, more finely chiseled beings with small hands and feet and slender necks, tender and fragile and neat.

Everywhere guitars. As soon as one guitar moves away, the sound of another takes its place, to continue this net of music that maintains one in flight from sadness, suspended in a realm of festivities.

Festivities. Fiestas. Holidays. Bursts of color and joy. Collective celebrations. Rituals. Indian feasts and Catholic feasts. Any cause will do. Even the very poor know how to dress up a town with colored paper cutouts which dance in the wind. What was happened to joy in America? The Americans in the hotel spend all their time drinking by the pool. The men go hunting flamingos, which they shoot for the pleasure of it. Or they fish for inedible mantarayas and weigh their spoils to win prizes.

The eyes of the Mexicans are full of burning life. They squat like Orientals next to wide, flat baskets full of fruit and vegetables arranged with a fine sense of design, of decorative art and harmonies. Strings of chili hang from the rafters. The scent of saffron, and rhythms of Chagall-colored laundry hanging like banners from windows, and in gardens. Warmth falls from the sky like the fleeciest blanket. Even the night comes without a change of temperature or alteration in the softness of the air. You can trust the night.

There is a rhythm in the way the women lift the water jugs onto their heads and walk balancing them. There is a rhythm in the way they carry their babies wrapped in their shawls, and their baskets filled with fruit. There is a rhythm in the way the fishermen pull in their nets in the evening, and the way the shepherds walk after their lambs and cows.

The first night here I showered and bathed hastily, feeling that perhaps the beauty and the velvety softness of the night might not last, that if I delayed, it would all change to coldness and harshness.

When I opened the screen door, the night lay unchanged, filled with tropical whisperings, as if leaves, birds, insects, and sea breezes possessed musicalities unknown to northern countries, as if the richness of the smells kept them all intoxicated, with the same aphrodisiac which affected me. Perfume of carnation and honeysuckle.

Through labyrinthian paths bordered with bushes which caress you as you walk, on stone warmed by the sun, I walk from my room to the large terrace where everyone sits and waits for dinner or to meet with friends.

The expanse of sky is like an infinite canvas on which human beings cannot project images from their memories because they would seem out of scale with the limitless sea, the limitless sky and the stars, which appear nearer and larger. So memory is absent, dissolved. I lie on a chaise longue to watch the spectacle of sunset and the night's first act. Nature so powerful and drugging that it annihilates memory. People seem warmer and nearer, as the stars seem nearer and the moon warmer.

The sea's orchestration carries away half the words and makes talking and laughing seem more like an accompaniment, like the sound of birds. Words have no weight. They float in space. They have a purely decorative quality, like flowers.

Why are people so fearful of the tropics? "All adventurers come to grief." I heard this many times, it was a refrain. Was it because they could not surrender to the overpowering effect of nature? They resisted it. I abandon myself to it and I feel strengthened by it rather than weakened.

La Perla is the hotel's night club. It is built of driftwood, and overlooks the wild part of the gorge between two mountains of rocks, against which the sea hurls itself with fury, defeated by the narrowness, and spilling its fury in high waves and foam. Into this narrow gorge Mexican boys dive for the tourists. First they climb the rocks slowly and laboriously, then they stand at the peak, pause for a moment, and dive like birds into the foaming, lashing waves.

Red ship's lanterns illumine a jazz band playing for a few dancers.

Because the hiss of the sea carries away some of the overtones, the main drumbeat seems more emphatic, like a giant heart pulsing.

Jazz is the music of the body. The breath comes through brass. It is the body's breath, and the strings' wails and moans are echoes of the body's music. It is the body's vibrations which ripple from the fingers. And the mystery of the withheld theme, known to jazz musicians alone, is like the mystery of our secret life. We give to others only peripheral improvisations.

I feel like a fugitive from the mysteries of the human labyrinth I was trying to pierce. I escaped my patterns. I escaped familiar and inexorable grooves. The outer world is so overwhelmingly beautiful that I am willing to stay outside, day and night, a wanderer and a pilgrim without abode.

I feel at home in Mexico, because I learned Spanish at the age of five, because the exuberance reminds me of my childhood in Spain, the singing reminds me of our Spanish maid Carmen, who sang all day while working. The gaiety in the streets, the children dancing, the flowerpots in the windows, the white-washed walls, the green shutters, the profusion of flowers, the liveliness of the people, all recall Barcelona and Havana. I realize that after years of life in America, I have finally learned to subdue my manners and my dress. I still remember that because my Cuban relatives sent me castoff clothes (and most dressing in Cuba was, as in Mexico, in a festive mood), I wore a red velvet dress to one of my jobs as model for a painter, and his expression when he saw me in a red velvet dress at nine in the morning was unforgettable. The walk with the weight on the heels, which Cubans and Spaniards do, the full-smile greeting, the gift for letting sorrow and worries slide off the shoulders, the predisposition for pleasure, all this is familiar and warm and comfortable.

Dr. Hernandez comes to the hotel several times a day for the tourists. He carries his black doctor's bag. He is my first friend here. After his visits he likes to sit on the terrace and talk a little and sip a drink.

He has written poetry, had a book published. He studied medicine in France. When he was first assigned to intern in Acapulco, he fought malaria, elephantiasis, and other tropical diseases. When his internship ended, he decided to stay on and practice.

He built a house on a protruding rock, extending out to the sea on the left of the Mirador, married, and had children. But his wife hates Acapulco and is always going to Mexico City because there are no schools for their children in Acapulco.

Since more than half of his life is given to the poor of Acapulco, to dramas and tragedies of all kinds, he does not like the tourists. "Because they live for pleasure only, because th

ey pamper themselves, because half of their ills are imaginary. Most of the time they call me because they are frightened of foreign countries and foreign food."

He talks to me at length since he was told I am a writer. He wants to take me on his tour of the people of Acapulco. I plead that I have been deprived of all pleasure and rest for years and have a right to a period without sorrows and burdens.

I met Annette at the Hotel Mirador. I was sitting in the dining room. A stairway leads from the upper terrace to the dining room. It is lighted from above and gives the diners time to see those who are coming down the stairs. My eyes were caught by the brilliant colors and the textures of her dress. I watched her for several evenings. She used the full palette of Mexican colors. She wore barbaric jewelry, copies and fantasies inspired by Mayan and Aztec themes. She had a mass of short, curled hair aureoled around her head, unruly, in the style of Toulouse-Lautrec women, and under this a delicately chiseled face, a small straight nose, fawn-colored eyes, and a slender neck poised on a voluptuous body. Her movements have a flow and sweep and vivacity and seductiveness. She undulates her hips, her breasts heave like the sea, she is never still.

We were introduced. Her liveliness and joyousness incarnated the spices and colors of Acapulco. She sometimes thrust her breasts forward or else she tilted her head backward, or she laughed with a ripple which ran through her whole body. It was as if she lived a semidance which kept the jewelry tinkling and her earrings mobile. She swung into the dining room with a mambo rhythm.

We became friends.

We talked on the terrace at night, after dinner, while waiting to see what the evening would bring. In spite of her children, two boys of seven and nine, men treated her like a young woman. Her laughter was inviting, and as she lay on the chaise longue, her body seemed offered. All its exotic and brilliant covering was a plumage, and she was uncomfortable within it, her natural state was nudity› or a brief bathing suit at the beach.

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

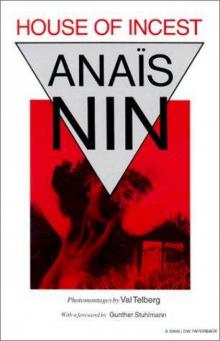

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest