Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

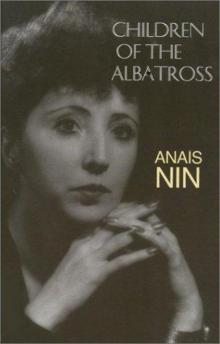

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

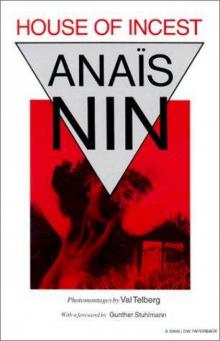

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest