The Winter of Artifice Read online

Page 11

She seemed to contemplate for a moment with great self-pity the isolation which this death of Hans as a god had brought upon her. The light of the street lamp struck her and it revealed the gesture of defeat so vividly that I found nothing to say.

This seeking of god in the dark city, this aimless wandering through the streets touching men and seeking god… this was a fear I had known too… seeking god in Hans, in live men, not in the past, not in the distance, but a god with arms, a god with a living breath, a god we wished to possess for ourselves, alone, in our own isolated woman’s soul. God was still inextricably woven with man and with man’s creation. Yet between this realm, this dark immediate realm which Johanna was weeping over, with her eyes fixed on the ground, I saw another sphere in the form of a circle. One circle issuing from the other. And I wanted to tell Johanna that we were moving from one circle into another, moving and rising, and that Johanna was only suffering from the pain of being thrust out of one circle into another, one groove into another, and that this leap it was which was the most difficult to make. The pain of parting with one’s faith, one’s old love, when one’s desire is rather to renew this faith and preserve the passion. But Johanna was weeping because Hans had said: “leave me alone,” or “let me work,” or “let me sleep.” And I found it impossible to explain to her what a struggle was required to emerge from the past clean of haunting memories and regrets. Impossible to explain to Johanna the inadequacy of our souls to cut life into final, total portions. Impossible to tell her that this pain, this great pain could be healed more quickly with a knowledge, a vision into the next circle. Impossible to answer Johanna’s great need of a frontier against which she might lean as upon a closed door, closing a door upon all pain. I could not take Johanna’s hand and make her raise her head and lead her into the new circle, raise her above pain and confusion, above ess of the city. And these sudden shafts of light upon us could not illumine the realm beyond, where the circle of pain closed and ended and one was raised into another circle. I could not help Johanna emerge out of the immediacy of her pain, leap beyond the strangle-hold of the present.

And so we continued to walk unsteadily over the dead leaves of his indifference, weeping together over an injustice which was as irremediable as the fall of dead leaves on our path. And I was kissing her because there was no other way to atone for a crime I had not committed, a crime ordained by the flux and continuity and mobility of life.

Johanna, Johanna, I wanted to say, will you walk thus with me when it is I who comes to the end of a circle, when it is I who shall be thrust out of the circle of Hans’ love?

* * *

When we met under the red light of the café we recognized in each other a mood of irony. We would dance together on our irony as on the chiming sparks of a dizzy star. We would laugh at him now, running with seven-leagued boots over the universe, laughing.

“He’s working so hard, so hard, he’s in a daze,” said Johanna. “He talks night and day about Death. I went to sleep the other night while he was talking to me.”

I was lonely, deep down, to think Hans had been at his work for two weeks without thinking of or noticing either of us. And my loneliness drew me close to Johanna.

“He was glad we were going out together,” continued Johanna rapidly. “He said it would give him a chance to work. He hasn’t any idea of time; he doesn’t even know what day of the week it is. He doesn’t give a damn about anybody or anything.”

A feeling of immense loneliness invaded Johanna.

We walked, as if we had wanted to walk away from our mood, as if we wanted to walk into another world. We walked up the hill of Montmartre, with houses lying on their sides like heather. We heard music, music so off tune that we did not recognize it as the music we heard every day. We slid into the shaft of light from where this music carne—into a room which seemed built of granified smoke and crystallized human breath. A room with a painted star on the ceiling, and a wooden, pock-marked Christ. Gusts of weary, petrified songs so dusty with use. Faces like empty glasses. The musicians made of rubber, like the elastic, cloud-like bouncing rubber-soled night.

“We hate Hans to-night. We hate man.”

The craving for caresses. Wanting and fighting the want. Both frightened by the vagueness of our desire, the indefiniteness of our craving. A rosary of question marks.

Johanna whispered:

“Let’s take drugs to-night.”

e pressed her strong knees against me, she inundated me with the moist brilliance of her eyes, the paleness of her face.

I shook my head, but I drank, I drank. No drink equal to the taste of war and hatred. No drink like bitterness.

I looked at Johanna’s fortune teller’s eyes, and at her taut profile like a tiger sniffing his prey in a bamboo sea.

“It takes all the pain away, it wipes out all the ugliness, all the foul, dirty reality.”

She leaned over the table until our breaths mingled, and she fixed her snake-like eyes upon me.

“You don’t know what a relief it is. The smoke of opium like fog. It brings marvellous dreams, and gaiety. Such gaiety, Djuna! And you feel so powerful, so powerful! You don’t feel any more frustration, you feel that you are lording it over the whole world, with a marvellous strength. No one can hurt you, humiliate you, confuse you. You feel that you are soaring over the world. Everything becomes larger and deeper. Such joys, Djuna, as you’ve never known or imagined. The touch of a hand is enough… the touch of a hand is like going the whole way… the tip of the finger on the breast can give an orgasm. And the time, how it flies! The days pass like an hour… it is all like down, so soft and lulling. You would love the heaviness of the body, the laziness, and the smells, the smells which fill the room. No more straining and desiring, just dreaming and floating and enjoying…”

“I’ve known all this without drugs,” I murmured.

“No, never as strongly, as powerfully. Everything you’ve ever known, every joy is a hundred times more acute, more overwhelming… Take drugs with me, Djuna. I want to do it with you. It’s with you I want to do it.”

I yielded, and consented with my head and my eyes. Then I saw that Johanna was looking at the Arab rug merchant who stood by the door, with his red hat, his kimono, and his slippers, his arms loaded with Arabian rugs and pearl necklaces. Under the rug I saw he had a wooden leg with which he was beating time to the jazz.

Johanna laughed hysterically, shaking her whole body with drunken laughter.

“You don’t know, Djuna… this man… with his wooden leg… you never can tell… he may have some. There was a man once, with a wooden leg like that. He was arrested and they found his wooden leg just packed with ‘snow’. Maybe I’ll go and ask him.”

And she got up with her heavy, animal walk, and talked to the rug merchant, looking up at him alluringly, begging, smiling up at him in that secret way she had of smiling at me. A burning pain invaded me to see Johanna begging. But the merchant shook his head, and smiled innocently, shook his head firmly and smiled, and offered her his rugs and the necklaces.

When I saw Johanna returning empty-handed I drank again, and it was like drinking fog, long draughts of fog.

We danced together, the floor turning under us like a phonograph record. Johanna dark and potent under the brim of her mannish hat.

A gust of jeers seemed to blow through the place. A gust of jeers. But we danced, cheeks touching, our cheeks chalice white. We danced, and the jeers cut into the haze and splendor of our dizziness like a whip. The eyes of the men were insulting us. The eyes of the men called us by the name the world had for us. Eyes. Green, jealous, crucified, tortured eyes. Eyes of the world. Eyes sick with hatred and contempt. Caressing eyes. Eyes ransacking our conscience. Stricken yellow eyes caught in the flare of a match. Heavy torpid eyes without courage, without dreams. Mockery. Frozen mockery.

Johanna and I wanted to strike those eyes, break them, break the bars of green wounded eyes condemning us. We wanted to break the

walls confining us, suffocating us. We wanted to break out from the prison of our own fears, break every obstacle. But all we found to break were glasses. We took our glasses and we broke them over our shoulders and we made no wish, but we looked at the fragments of the glasses on the floor wonderingly, as if our mood might be lying there also, in broken pieces.

We danced mockingly, as if we were sliding beyond the reach of the men’s hands, running like sand between their insults. We scoffed at these eyes which brimmed with knowledge, for we knew the ecstasy of mystery, and of fog, and the words they uttered fell like heavy stones through the fog of our ecstasy. The eyes and the words of men fell through like stones, while we danced mockingly away and down the rolling hills of fog, fire and orange fumes of a world we had seen through a slit in the dream. Spinning and reeling and falling, spinning and turning and rolling down the brume and smoke of a world seen through a slit in the dream.

The waiter put his ham-colored hand on Johanna’s arm:

“You’ve got to get out of here, you two!”

* * *

I arrived with a bottle of vodka under my arm. I was already drunk—on the idea of the vodka. A high drunkenness, like an Arabian magic carpet.

I found Johanna in a sullen mood, sullen as a gypsy, a rampant dark sullenness, earth-colored, snake- tongued.

Hans came out of the kitchen looking pale, abstracted. He came out with a dazed expression, as if he had left his body on the table with the thick manuscript he had been slaving over.

“Look at him,” said Johanna, “that’s the ghost I have to live with.”

The bottle of vodka stood on the kitchen table. Hans put his hands around it lovingly, absentmindedly.

The three of us were now sitting around the stained kitchen table, looking mutely at the bottle of vodka. Suddenly Johanna pounced on it, uncorked it swiftly, and spilled out three brimming glasses of it.

“metimes,” said Johanna, “when I read what you’ve had to say about me, I don’t know whether I’m a goddess, a whore, or a criminal.”

“You flatter yourself,” said Hans, and I saw that his eyes were cruel and angry, his face flushed, and that he was looking at me too with a secret, vengeful anger which the drink had brought to the surface.

“To-day I was looking at a necklace in the Trocadero,” he continued. “A necklace which would have suited either of you. It was a big, clumsy necklace of bones which the men of Africa used to put around the necks of the women who lied. It would have suited you swell, the two of you!”

And he drank some more.

I felt a deep disquietude. I felt this anger, this hatred flaring up between us like a strong, brutal wind; I felt caught up by it, and at the same time, in some strange, inexplicable way, I felt unwilling to defend myself. It was like the taste of something acrid and new, like a poison, like a simoun storm in the desert, which made one nervous and yet heavy with fever. I picked up my vodka and drank with them—as if to signify my deep desire to sink with them into that dark, fiery realm of war and hate.

And then I noticed that Johanna’s body had begun to loosen visibly, that it had become like lead. I saw her mouth widening, saw her eyes growing bleary, her legs outstretched, heavy, inert, wooden. Johanna had suddenly lost her luminosity. Johanna suddenly looked to me exactly like a common, ordinary whore.

As the fiery vodka dulled me, I felt immensely weary of my constant ascensions. I wanted to be lost with Hans and Johanna, to yield, to forget my name and identity, and all that was expected of me, my promises and my pursuit of perfection. I wanted to follow Hans and Johanna into disorder, and indifference, and carelessness, and unscrupulousness, to borrow and take and beg and live only in the moment…

I laughed and said: “This vodka is like the sun, it burns all caring away, it burns consciousness away, it burns everything away…”

But when I saw the looseness of Johanna’s mouth and the abandon of her body on the chair, I said in a heavy voice:

“I don’t like you when you’re drunk, Johanna.”

Hans toppled over and fell asleep against the table, hiding his flushed red face in his arms, and laughing softly now and then.

Johanna’s Viking body was crumbling. I tried to drag her to bed, but she was too heavy for me. Like David I could fling stones at Goliath, but a drunken Goliath I could not carry to bed.

Hans awakened and helped me, tottering as he did so under the burden.

Johanna laughed, wept, vomited… In keeping with her role Johanna was going through the gestures which I had imagined myself to be making when I had seen Johanna drunk. It was Johanna who vomited for me all the lives and adventures I had embellished by the alchemy of illusion. I vomited with Johann the reality of adventure, my desire for drunkenness, for high color, for excess. Absolute drunkenness cancels the joys of drunkenness, intense living destroys intensity, reality destroys the dream. Everything beautiful has to remain suspended and unfinished.

Johanna wept, laughed, and threw the towels at my face. I wiped the floor.

Johanna raved:

“I love you, you are cruel and clever. You have been cruel and clever, Djuna, that’s why I got drunk. You’re cruel, terribly cruel.”

But when Johanna said I love you, it had the emptiness of a gasp. She had exhausted the meaning and potency of these words with her comedies. It was an automatic gasp. The impetus was feeble, deflated. Automatically she might repeat for ever “I love you,” but the actress in her had exhausted the potency of the words.

She was like a foaming sea, Johanna, a sea churning up wreckage, skeletons of ships which I had glimpsed in full sailing. The debris of her doubts and fears: “Hans, Djuna, you’re both too cruel and clever. I’m afraid of you both.”

At this moment I remembered the face of Johanna, the child staring through the dimmed taxi window, but before this caricature of Johanna’s distress, the pity I had felt then was gone.

Pity, illusion, the dream, all had been spilled in vomit, wiped up, washed down the sewer and lost.

Johanna slid off the bed and had to be hoisted back again. Hans was laughing softly, drunkenly, as he wiped the floor.

But I was unable to laugh. I was enslaved by my own inexorable seriousness. It seemed to have devolved on me, the weary task of representing tragedy, the necessity of bearing up my seriousness in spite of all ridicule. The discarded seriousness of others had fallen on my shoulders because I had known always that those who discard tragedy like an old glove or a frayed collar are throwing away something the preciousness of which was always clear to me. Exactly as if I had become a kind of rag-picker for the fragments of tragedy.

Driven again by this ridiculous seriousness, I stood there in the middle of the room, unable to laugh with Hans. I was caressing Johanna and putting cold rags on her forehead. I was vomiting with Johanna all the illusions, fantasies, grandiose gestures, colorful extravagances, vertigoes so seriously and noiselessly. In keeping with her destiny Johanna was continuing to add to the chain of her external movements, expressions and gestures.

I lay all dressed at Johanna’s side. My first night with Johanna. No more Johanna. The stench of vomit. A body. Earth. A body. Heavy earth. Inert earth. Johanna!

I craved at this moment the supreme drunkenness of creation. I was hungry again for my own ecstasies, my solitude, my lightness, my joys. My ecstasies without vomit: not those which filled the being with poisons which must afterwards be ejected as the whore that men empty themselves into is ejected at dawn.

Then came the moment when a curtain seemed to fall over my life. As this curtain fell, I strove wistfully to gather up the last movements. Johanna and I had been walking together in sandalled feet. I had seen the sandalled feet treading the asphalt. I had looked down at them and said thoughtfully: “I like to see ourselves walking.”

Because I was already no longer walking, neither walking, nor eating, nor sleeping. I was already writing—writing even as the curtain descended. I had yielded my maximum of human feelings. I

had ceased to exist. I had lost my human-ness. And before Johanna had become aware of this transformation, I had run away. The human being in me was dead.

Johanna had given me violets. I vomited them up too. Violets. More things. Another abortion. Trying to efface the failure of one gesture with another. Objects. The world of things, which in the end turns the stomach. These violets had been extremely touching. Johanna, still heavy-headed, after having torn down her pyramid of illusions, had rushed to buy me violets, to atone. Very sublime, these violets which I had thrown away. But I would not let myself be bribed. The violets were crushed between the tin-voiced typewriter keys. And with violet ink I recorded the night.

The following night I returned to Johanna.

* * *

We were alone.

We were alone without daylight, without past, without any thought of the resemblance between our togetherness and the union of other women. The whole world was being pushed to one side by our faith in our own uniqueness. All comparison was proudly discarded. Johanna and I alone, naked of knowledge and naked of other experiences. We remembered nothing before this hour; we were innocent of associations. We forgot what we had read in books, what we had seen in cafés, the laughter of men, and the mocking participation of other women. Our individuality washed down and effaced the universe. We stood at the beginning of everything. We were naked and innocent of the past.

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

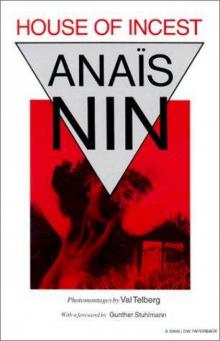

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest