The Winter of Artifice Read online

Page 13

Since that day I have not seen my father. Twenty years have passed. He is coming to-day. I am thirty years old…

We entered New York harbor, my mother, my two brothers and I, in the midst of a violent thunderstorm. The Spaniards aboard the ship were terrified; some of them were kneeling in prayer. They had reason to be terrified—the bow of the ship had been struck by lightning. When finally we came alongside the pier a group of newsboys clambered up the gangplank shouting “Extra! Extra!” We learned that war had been declared. I saw the passengers reading the papers excitedly. I knew that something terrible had happened, but I was indifferent, I had no desire to read about the war. I busied myself making a last minute entry in my diary, the diary which I had begun when we left Barcelona.

I had intended to send my father the first volume of my diary as soon as it was finished. It was a monologue, or dialogue, dedicated to him, inspired by the superabundance of thoughts and feelings caused by the pain of leaving him. With the sea between us I felt that at least I might be able to reveal to him my innermost thoughts. that I might be able to reveal to him with absolute sincerity the great love I bore him, as well as my sadness and my yearning.

We arrived in New York with huge wicker baskets, a cage full of birds, a violin case and no money. I carried my diary in a basket. I was timid, withdrawn. I caught only fleeting patches of this new reality surrounding me. At the pier there were aunts and cousins awaiting us. The negro porters threw themselves on our belongings. I remember vividly how I clung to my brother’s violin case. I wanted everybody to know that I was an artist.

Entering the subway I observe immediately what a strange place New York is—the staircases move up and down by themselves. And in the train hundreds of mouths chewing, masticating. My little brother asks: “Are Americans ruminants?”

I am eleven years old. My mother is absent most of the day searching for work. There are socks to darn and dishes to wash. I have to bathe and dress my brothers. I have to amuse them, aid them with their lessons. The days are full of bleak effort in which great sacrifices are demanded of all of us. Though I experience a tremendous relief in helping my mother, in serving her faithfully, I feel nevertheless that the color and the fragrance has gone out of our life. When I hear music, when I hear laughter and talk in the room where my mother gives singing lessons, I am saddened by a feeling of something lost.

And so, little by little. I shut myself up within the walls of my diary. I hold long conversations with myself, through the diary. I talk to my diary, address it by name, as if it were a living person, my other self perhaps. Looking out the window which gives on our ugly backyard I imagine to myself that I am looking at parks, castles, golden grilles, and exotic flowers. Within the covers of the diary I create another world wherein I tell the truth, in contrast to the multiple lies which I spin when I am conversing with others, as for instance telling my playmates that I had travelled all around the world, describing to them the places which I had read about in my father’s library.

The yearning for my father becomes a long, continuittle. plaint. Every page contains pleas to him, invocations to God to reunite us—hours and hours of suffocating moods, of dreams and reveries, of feverish restlessness, of morbid, sombre memories and longings. I cannot bear to listen to music, especially the arias my mother sings—”Ever since the day,” “Some day he’ll come,” etc. She seems to choose only the songs which will remind me of him.

I feel crippled, lost, transplanted, rebellious. I am alone a great deal. My mother is healthy, exuberant, full of plans for the future. When I am moody she chides me. If I confess to her she laughs at me. She seems to doubt the sincerity of my feelings. She attributes my moods to my over-developed imagination, or else she lays it to my blood. When she is angry she shouts: “Mauvaise graine, va!” She is often angry now, but not with us. She is obliged to fight for us every day of her life. It requires all her courage, all her buoyancy and optimism, to face the world. New York is hostile, cold, indifferent.

We are immigrants, and we are made to feel it. Even on Christmas Eve we are left alone—she has to sing at the church in order to earn a few pennies.

The great crime, she makes us feel, is our resemblance to our father. Each flare of temper, each tragic outburst is severely condemned. Even my paleness serves to remind her of him. “He too always looked pale and ready to die, but it was all nonsense,” she says. Every day she adds a little touch to the image we have kept of him. My younger brother’s rages, his wildness, his destructiveness, all this comes from Father. My imagination, my exaggerations, my fantasies, my lies, my beautiful edifice of lies, these too spring from my father.

It is true. Everything springs from him, even the lies which originated from the books I had read in his library. When I told the children at school that I had once travelled through Russia in a covered wagon it was not a lie either, because in my mind I had made this journey through snow-covered Russia time and time again. The cold of New York revived the memories of my father’s books, of the journeys I longed to take with him whenever I saw him go away. To face the cold of New York required a superhuman effort. Standing in the snow in Central Park feeding the pigeons I wanted to die. The dread of facing the snow and frost each morning paralyzed me. Our school was only around the corner, but I had not the courage to leave the house. My mother had to ask the negro janitor to drag me to school. “Po’ thing,” he would say, “you ought to live down south.” He would lend me his woollen gloves and slap me to get warm…

Only in the diary could I reveal my true self, my true feelings. What I really desired was to be left alone with my diary and my dreams of my father. In solitude I was happy. My head was seething with ideas. I described every phase of our life in detail, minute, childish details which seem ridiculous and absurd now, but which were intended to convey to my father the need that we felt for his presence. Though I detested New York I painted a picture of it in glowing terms, hoping that it would entice him to come. And when at last I had finished the first volume of my diary, when I had wrapped it tenderly and addressed it to him in my own hand, my mother informed me sorrowfully that it was useless to send it to him because mail from America would never reach Paris. She bade me wait until the war was concluded.

And so once again I am thrust backinto my world of illusion. When, in order to amuse my brothers, I impersonate Marie-Antoinette as she marches proudly to the guillotine, I stand on a chariot of chairs with a white lace cap and I weep real tears. I weep over the martyrdom of Marie-Antoinette because I am aware of my own martyrdom. A million times my hair will turn white overnight and the crowd jeer at me. A million times I will lose my throne, my husband, my children, and my life. At eleven years of age I am searching, in the lives of the great, for analogies to the drama and events of my own life which I feel is destined to be shattered at every turn of the road. In acting the roles of other personages I feel that I am piecing together the fragments of my shattered life. Only in the fever of creation can I recreate my own lost life. When in the thunderous voice of Marat I demand a hundred thousand heads I am demanding the vengeance which later I will take with my own hands.

There is a passage in this early diary wherein I say that I would like to relive my life in Spain. It amazes me now when I reread it. Already, at that early age, I was bemoaning the irreversibility of life. Already I was aware of how the past dies. I reexamine what I had written about New York for my father because I feel that I have not done justice to it. I watch each minute of the day as I live so that nothing will be lost. I regret the minutes passing. I weep without knowing why, since I am young and have not yet known any real suffering. But, without being fully aware of it, I had already experienced my greatest sorrow, the irreparable loss of my father. I did not know it then, as indeed most of us never know when it is that we experience the full measure of joy, or of sorrow. But our feelings penetrate us like a poison of undetectable nature. We have sorrows of which we do not know the origin or name.

I had never openly expressed my love to my father. He thought me proud and isolate, and strange and wayward. My mother regarded me as an actress. Neither of them believed in me, neither of them took me into their confidence. And it was so terribly necessary that I have some one to confide in, some one who would listen and silently assent, or silently pass judgment on my doings. But there was no one.

I remember a night before Christmas when, in utter desperation, I began to believe that my father was coming, that he would arrive Christmas Day. Even though it was that very day I had received a postcard from him, even though I was obliged to admit to myself that Arcachon was indeed too far away for my hopes to be realized, still a sense of the miraculous impelled me to expect what was humanly impossible. I got down on my knees and I prayed to God to perform a miracle. I looked for my father all Christmas Day, and again on my birthday, a month or so later. To-day he will come. Or to-morrow. Or the next day. Each disappointment was baffling and terrifying to me.

To-day he is coming. I am sure of it. But how can I be sure? I amstanding on the edge of a crater.

My true God was my father. At communion it was my father I received, and not God. I closed my eyes and swallowed the white bread with blissful tremors. I embraced my father in holy communion. My exaltation fused into a semblance of holiness. I aspired to saintliness in order to conceal the secret love which I guarded so jealously in my diary. The voluptuous tears at night when I prayed to God, the joy without name when I stood in his presence, the inexplicable bliss at communion, because then I talked with my father and I kissed him.

I worshipped him so passionately that I grew old and the form of his image grew blurred. But I had not lost him. His image was buried deep in the most mysterious regions of my being. On the surface there remained the image created by my mother—his egoism, his neglectfulness, his irresponsibility, his love of luxury. When for a time my immense yearning seemed to have exhausted itself, when it appeared that I had almost forgotten this man whom my mother described so bitterly, it was only the announcement of the fact that his image had become fluid; it ran in subterranean channels, through my blood. Consciously I was no longer aware of him; but in another way his existence was even stronger than before. Submerged, yet magically ineffaceable, he floated in my blood.

At thirteen I record in my diary that I want to marry a man who looks like the Count of Monte Cristo. Apart from the mention of black eyes it is my father’s portrait which I give: “A man so strong… with very white teeth, with a pale and mysterious face… a grave walk, a distant smile… I would like him to tell me all about his life, a very sad life, full of harrowing adventures… I would like him to be proud and haughty… to play some instrument…”

The image created by my mother, added to the blurred memories of a child, do not compose a being; yet in my haunting quest I fashioned an imagined individual whose fragments I pursued relentlessly. The blue eyes of a boy in school, the talent of a young violinist, a pale face seen in the street—these fleeting aspects of the image that was buried deep in my blood moved me to tears. To listen to music was unbearable. When my mother sang I exhausted myself in sobs.

In this record which I have faithfully kept for twenty years I speak of my diary as of my shadow, my double; I say I will only marry my double. As far as I knew this double was the diary which was full of reflections, like a mirror, which could change shape and color and serve all kinds of imaginative substitutions. This diary which I had intended to send to my father, which was to be a revelation of my love for him, became by an accident of fate a secretive thing, another wall between myself and that world which it seemed forbidden me ever to enter.

I would have liked great love and affection, confidence, openness. My father, I felt certain, would have rejected me—his standards were too severe. I wrote him once that I thought he had abandoned me because I was not an intelligent nor pretty enough daughter. I was a perpetually offended being who fancied that she was not wanted. This fear of not being wanted weighed down on me like a perpetual icy condemnation.

To-day, when he arrives, will I be able to lift my head? Will I be able to keep my head lifted, will I be able to stand the cold look in his eyes when I raise my eyes to his? Will my body not tremble with fear when I hear his voice? After twenty years I am still obsessed by the fear of him. But now I feel that it is in his power to absolve me of all fear. Perhaps it is he who will fear me. Perhaps he is coming to receive the judgment which I alone can mete out to him. To-day the circle of empty waiting will be broken. I am waiting for him to embrace me, to say with his own lips that he loves me. I have made a God of him and I have been punished. Now when he comes I want to make him a man again, to make him a human father. I do not want to fear him any longer. I do not want to write another line in my diary. I want him to smash this monument which I have erected to him and accept me in my own right. To-day when he comes I want to tear out this secret which I have kept inside me so long. It is strangling me. I want him to come and deliver me.

He is coming now. I hear his steps.

* * *

I expected the man of the photographs, the young man of the photographs. I had not tried to imagine what twenty years had done to his face.

It was not any older, there were no wrinkles in it, but there was a mask over it. His face was a mask. The skin did not match the sensitive skin of his wrists. It seemed made of earth and papier mâché. It was not pure skin. There must have been a little space between it and the real face, a little partition through which the breeze could sing, and behind this mask another smile, another face, and skin like that of his wrists, white and vulnerable.

At the sight of me waiting on the doorstep he smiled, a feminine smile, and moved towards me with a neat compact grace, ease, youthfulness.

I felt unsettled. This man coming towards me did not seem at all like a father. It seemed to me that his first words were words of apology. After he had taken off his gloves, and verified by his watch that he was on time—it was very important to him to be on time—after he had kissed me and told me that I had become very beautiful, almost immediately it seemed to me that I was listening to an apology, an explanation of why he had left us. It was as if behind me there stood a judge, a tall judge whom I could not see, and to this judge my father addressed a beautifully polished speech, a marvellous speech to which I listened with admiration, for the logic was so beautiful, the smooth chain of phrases, the long and flawless story of my mother’s imperfections, of all that he had suffered, the manner in which all the facts of their life were presented, all made a perfect and eloquent pleading, addressed to a judge I could not see and with whom I had nothing to do. He had not come out free of his past. Taking out a gold-tipped cigarette and with infinite care placing it in a holder which contained a filter for the nicotine, he related the story I had heard from my mother, all with an accent of apology and defense.

I had no time to tell him that I understood that they had not been made to live together, that it was not a question of faults and defects, but of alchemy, that this alchemy had created war, that there was no one to blame or to judge but their marriage. Already my father was launched on an apology of why he had stayed all winter in the south; he did not say that he had enjoyed it, but that it had been absolutely necessary to his well-being. It seemed to me as he talked that he was just as ashamed to have left us as he was of having spent the winter in the South when he should have been in Paris giving concerts.

I waited for him to lose sight of this judge standing behind me for which I was not responsible and then, plunging into the present, into our present, I said:

“It’s scandalous to have such a young father.”

“Do you know what I used to fear?” h said. “That you might come too late to see me laughing—too late for me to have the power to make you laugh. In June when I go South again you must come with me. They will take you for my mistress, that’s certain. It will be delightful.”

I was standing against the mantelpiec

e. He was looking at my hands, admiring them. I jerked backwards, pushing the crystal bowl against the wall. It cracked and the water gushed forth as from a fountain, splashing all over the floor. The glass ship could no longer sail away—it was lying on its side, on the rock crystal stones.

We stood looking at the broken bowl and at the water forming a pool on the floor.

“Perhaps I’ve arrived at my port at last,” I said. “Perhaps I’ve come to the end of my wanderings. I have found you.”

“We’ve both done a lot of wandering,” he said.

“I not only played the piano in every city of the world… sometimes when I look at the map, it seems to me that even the tiniest villages could be replaced by the names of women. Wouldn’t it be funny if I had a map of women, of all the women I have known before you, of all the women I have had? Fortunately I am a musician, and my women remain incognito. When I think about them it comes out as a do or a la, and who could recognize them in a sonata? What husband would come and kill me for expressing my passion for his wife in terms of a quartet?”

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

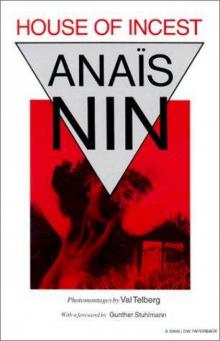

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest