The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Read online

Page 2

But finally they had agreed that she would throw a stone from the street to the roof of the barge to warn Rango of her arrival and that he would meet her at the top of the stairs.

This night she tried to laugh at her fears and to walk down alone. But when she reached the barge there was no light in the bedroom, and no Rango to meet her, but the old watcan popped out of the trap door, vacillating with drink, red-eyed and stuttering.

Djuna said: “Has Monsieur arrived?”

“Of course, he’s in there. Why don’t you come down? Come down, come down.”

But Djuna did not see any light in the room, and she knew that if Rango were there, he would hear her voice and come out to meet her.

The old watchman kept the trap door open, saying as he stamped his feet: “Why don’t you come down? What’s the matter with you?” with more and more irritability.

Djuna knew he was drunk. She feared him, and she started to leave. As his rage grew, she felt more and more certain she should leave.

The old watchman’s imprecations followed her.

Alone at the top of the stairs, in the silence, in the dark, she was filled with fears. What was the old man doing there at the trap door? Had he hurt Rango? Was Rango in the room? The old watchman had been told he could no longer stay on the barge. Perhaps he had avenged himself. If Rango were hurt, she would die of sorrow.

Perhaps Rango had come by way of the other bridge.

It was one o’clock. She would throw another stone on the roof and see if he responded.

As she picked up the stone, Rango arrived.

Returning to the barge together, they found the old watchman still there, muttering to himself.

Rango was quick to anger and violence. He said: “You’ve been told to move out. You can leave immediately.”

The old watchman locked himself in his cabin and continued to hurl insults.

“I won’t leave for eight days,” he shouted. “I was captain once, and I can be a captain any time I choose again. No black man is going to get me out of here. I have a right to be here.”

Rango wanted to throw him out, but Djuna held him back.

“He’s drunk. He’ll be quiet tomorrow.”

All night the watchman danced, spat, snored, cursed, and threatened. He drummed on his tin plate.

Rango’s anger grew, and Djuna remembered other people saying: “The old man is stronger than he looks. I’ve seen him knock down a man like nothing.” She knew Rango was stronger, but she feared the old man’s treachery. A stab in the back, an investigation, a scandal. Above all, Rango might be hurt.

“Leave the barge and let me attend to him,” said Rango. Djuna dissuaded him, calmed his anger, and they fell asp at dawn.

When they came out at noon, the old watchman was already on the quays, drinking red wine with the hobos, spitting into the river as they passed, with ostentatious disdain.

The bed was low on the floor; the tarred beams creaked over their heads. The stove was snoring heat, the river water patted the barge’s sides, and the street lamps from the bridge threw a faint yellow light into the room.

When Rango began to take Djuna’s shoes off, to warm her feet in his hands, the old man of the river began to shout and sing, throwing his cooking pans against the wall:

Nanette gives freely

what others charge for.

Nanette is generous,

Nanette gives love

Under a red lantern

Rango leaped up, furious, eyes and hair wild, big body tense, and rushed to the old man’s cabin. He knocked on the door. The song stopped for an instant, and was resumed:

Nanette wore a ribbon

In her black hair.

Nanette never counted

All she gave…

Then he drummed on his tin plate and was silent.

“Open the door!” shouted Rango.

Silence.

Then Rango hurled himself against the door, which gave way and tore into splinters.

The old watchman lay half naked on a pile of rags, with his beret on his head, soup stains on his beard, holding a stick which shook from terror.

Rango looked like Peter the Great, six feet tall, black hair flying, all set for battle.

“Get out of here!”

The old man was dazed with drunkenness, and he refused to move. His cabin smelled so badly that Djuna stepped back. There were pots and pans all over the floor, unwashed, and hundreds of old wine bottles exuding a rancid odor.

Rango forced Djuna back into e bedroom and went to fetch the police.

Djuna heard Rango return with the policeman, and heard his explanations. She heard the policeman say to the watchman: “Get dressed. The owner told you to leave. I have an injunction here. Get dressed.”

The watchman lay there, fumbling for his clothes. He could not find the top of his pants. He kept looking down into one of the pant’s legs as if surprised at its smallness. He mumbled. The policeman waited. They could not dress him because he would turn limp. He kept muttering: “Well, what do I care? I used to be captain of a yacht. Something white and smart, not one of these broken-down barges. I used to have a white suit, too. Suppose you do throw me into the river, it’s all the same to me. I don’t care if I die. I’m not a bad old man. I run errands for you, don’t I? I fetch water, don’t I? I bring coal. What if I do sing a bit at night?”

“You don’t just sing a bit,” said Rango. “You make a hell of a noise every time you come home. You bang your pails together, you raise hell, you bang on the walls, you’re always drunk, you fall down the stairs.”

“I was sound asleep, wasn’t I? Sound asleep, I tell you. Who knocked the door down, tell me? Who broke into my cabin? I’ll not get out. I can’t find my pants. These aren’t mine, they’re too small.”

Then he began to sing:

Laissez moi tranquille,

Je ferais le mort.

Ma chandelle est morte

Et ma femme aussi.

Then Rango, the policeman, and Djuna all began to laugh. No one could stop laughing. The old man looked so dazed and innocent.

“You can stay if you’re quiet,” said Rango.

“If you’re not quiet,” said the policeman, “I’ll come back and fetch you and throw you in jail.”

“Je ferais le mort,”said the old man. “You’ll never know I’m here.”

He was now thoroughly bewildered and docile. “But no one has a right to knock a door down. What manners, I tell you! I’ve knocked men down often enough, but never knocked a door down. No privacy left. No manners.”

When Rango returned to the bedroom, he found Djuna still laughing. He opened his arms. She hid her face against his coat and said: “You know, I love the way you broke that door.” She felt relieved of some secret accumulation of violence, as one does watching a storm of nature, thunder and lightning discharging anger for us.

“I loved your breaking down that door,” repeated Djuna.

Through Rango she had breathed some other realm she had never attained before. She had touched through his act some climate of violence she had never known before.

The Seine River began to swell from the rains and to rise high above the watermark painted on the stones in the Middle Ages. It covered the quays at first with a thin layer of water, and the hobos quartered under the bridge had to move to their country homes under the trees. Then it lapped the foot of the stairway, ascended one step, and then another, and at last settled at the eighth, deep enough to drown a man.

The barges stationed there rose with it; the barge dwellers had to lower their rowboats and row to shore, climb up a rope ladder to the wall, climb over the wall to the firm ground. Strollers loved to watch this ritual, like a gentle invasion of the city by the barges’ population.

At night the ceremony was perilous, and rowing back and forth from the barges was not without difficulties. As the river swelled, the currents became violent. The smiling Seine showed a more ominous aspect of its charact

er.

The rope ladder was ancient, and some of its solidity undermined by time.

Rango’s chivalrous behavior was suited to the circumstances; he helped Djuna climb over the wall without showing too much of the scalloped sea-shell edge of her petticoat to the curious bystanders; he then carried her into the rowboat, and rowed with vigor. He stood up at first and with a pole pushed the boat away from the shore, as it had a tendency to be pushed by the current against the stairway, then another current would absorb it in the opposite direction, and he had to fight to avoid sailing down the Seine.

His pants rolled up, his strong dark legs bare, his hair wild in the wind, his muscular arms taut, he smiled with enjoyment of his power, and Djuna lay back and allowed herself to be rescued each time anew, or to be rowed like a great lady of Venice.

Rango would not let the watchman row them across. He wanted to be the one to row his lady to the barge. He wanted to master the tumultuous current for her, to land her safely in their home, to feel that he abducted her from the land, from the city of Paris, to shelter and conceal her in his own tower of love.

At the hour of midnight, when others are dreaming of firesides and bedroom slippers, of finding a taxi to reach home from the theatre, or pursuing false gaieties in the bars, Rango and Djuna lived an epic rescue, a battle with an angry river, a journey into difficulties, wet feet, wet clothes, an adventure in which the love, the test of the love, and the reward telescoped into one moment of wholeness. For Djuna felt that if Rango fell and were drowned she would die also, and Rango felt that if Djuna fell into the icy river he would die to save her. In this instant of danger they realized they were each other’s reason for living, and into this instant they threw their whole beings.

Rango rowed as if they were lost at sea,ot in the heart of a city; and Djuna sat and watched him with admiration, as if this were a medieval tournament and his mastering of the Seine a supreme votive offering to her feminine power.

Out of worship and out of love he would let no one light the stove for her either, as if he would be the warmth and the fire to dry and warm her feet. He carried her down the trap door into the freezing room damp with winter fog. She stood shivering while he made the fire with an intensity into which he poured his desire to warm her, so that it no longer seemed like an ordinary stove smoking and balking, or Rango an ordinary man lighting wood with damp newspapers, but like some Valkyrian hero lighting a fire in a Black Forest.

Thus love and desire restored to small actions their large dimensions, and renewed in one winter night in Paris the full stature of the myth.

She laughed as he won his first leaping flame and said: “You are the God of Fire.”

He took her so deeply into his warmth, shutting the door of their love so intimately that no corroding external air might enter.

And now they were content, having attained all lovers’ dream of a desert island, a cell, a cocoon, in which to create a world together from the beginning.

In the dark they gave each other their many selves, avoiding only the more recent ones, the story of the years before they met as a dangerous realm from which might spring dissensions, doubts, and jealousies. In the dark they sought rather to give each other their earlier, their innocent, unpossessed selves.

This was the paradise to which every lover liked to return with his beloved, recapturing a virgin self to give one another.

Washed of the past by their caresses, they returned to their adolescence together.

Djuna felt herself at this moment a very young girl, she felt again the physical imprint of the crucifix she had worn at her throat, the incense of mass in her nostrils. She remembered the little altar at her bedside, the smell of candles, the faded artificial flowers, the face of the virgin, and the sense of death and sin so inextricably entangled in her child’s head. She felt her breasts small again in her modest dress, and her legs tightly pressed together. She was now the first girl he had loved, the one he had gone to visit on his horse, having traveled all night across the mountains to catch a glimpse of her. Her face was the face of this girl with whom he had talked only through an iron gate. Her face was the face of his dreams, a face with the wide space between the eyes of the madonnas of the sixteenth century. He would marry this girl and keep her jealously to himself like an Arab husband, and she would never be seen or known to the world.

In the depth of this love, under the vast tent of this love, as he talked of his childhood, he recovered his innocence too, an innocence much greater than the first, because it did not stem from ignorance, from fear, or from neutrality in experience. It was born like an ultimate pure gold out of many tests, selections, from voluntary rejection of dross. It was born of courage, after desecrations, from much deeper layers of the being inaccessible to youth.

Rango talked in the night. “The mountain I was born on was an extinct volcano. It was nearer to the moon. The moon there was so immense it frightened man. It appeared at times with a red halo, occupying half of the sky, and everything was stained red… There was a bird we hunted, whose life was so tough that after we shot him the Indians had to tear out two of his feathers and plunge them into the back of the bird’s neck, otherwise it would not die… We killed ducks in the marshes, and once I was caught in quicksands and saved myself by getting quickly out of my boots and leaping to safe ground… There was a tame eagle who nestled on our roof… At dawn my mother would gather the entire household together and recite the rosary… On Sundays we gave formal dinners which lasted all afternoon. I still remember the taste of the chocolate, which was thick and sweet, Spanish fashion… Prelates and cardinals came in their purple and gold finery. We led the life of sixteenth-century Spain. The immensity of nature around us caused a kind of trance. So immense it gave sadness and loneliness. Europe seemed so small, so shabby at first, after Guatemala. A toy moon, I said, a toy sea, such small houses and gardens. At home it took six hours by train and three weeks on horseback to reach the top of the mountain where we went hunting. We would stay there for months, sleeping on the ground. It had to be done slowly because of the strain on the heart. Beyond a certain height the horses and mules could not stand it; they would bleed through mouth and ears. When we reached the snow caps, the air was almost black with intensity. We would look down sharp cliffs, thousands of miles down, and we would see below, the small, intensely green, luxuriant tropical jungle. Sometimes for hours and hours my horse would travel alongside a waterfall, until the sound of the falling water would hypnotize me. And all this time, in snow and wildness, I dreamed of a pale slender woman… When I was seventeen, I was in love with a small statue of a Spanish virgin, who had the wide space between the eyes which you have. I dreamed of this woman, who was you, and I dreamed of cities, of living in cities… Up in the mountain where I was born one never walked on level ground, one walked always on stairways, an eternal stairway toward the sky, made of gigantic square stones. No one knows how the Indians were able to pile these stones one upon another; it seems humanly impossible. It seemed more like a stairway made by gods, because the steps were higher than a man’s step could encompass. They were built for giant gods, for the Mayan giants carved in granite, those who drank the blood of sacrifices, those who laughed at the puny efforts of men who tired of taking such big steps up the flanks of mountains. Volcanoes often erupted and covered the Indians with fire and lava and ashes. Some were caught descending the rocks, shoulders bowed, and frozen in the lava, as if cursed by the earth, by maledictions from the bowels of the earth. We sometimes found traces of footsteps bigger than our own. Could they have been the white boots of the Mayans? Where I was born the world began. Where I was born lay cities buried under lava, children not yet born destroyed by volcanoes. There was no sea up there, but a lake capable of equally violent storms. The wind was so sharp at times it seemed as if it would behead one. The clouds were pierced by sandstorms, the lava froze in the shape of stars, the trees died of fevers and shed ashen leaves, the dew steamed where it fell, and clouds r

ose from the earth’s parched cracked lips… And there I was born. And the first memory I have is not like other children’s; my first memory is of a python devouring a cow… The poor Indians did not have the money to buy coffins for their dead. When bodies are not placed in coffins a combustion takes place, little explosions andue flames, as the sulphur burns. These little blue flames seen at night are weird and frightening… To reach our house we had to cross a river. Then came the front patio which was as large as the Place Vendome… Then came the chapel which belonged to our ranch. A priest was sent for from town every Sunday to say mass… The house was large and rambling, with many inner patios. It was built of pale coral stucco. There was one room entirely filled with firearms, all hanging on the walls. Another room filled with books. I still remember the cedar-wood smell of my father’s room. I loved his elegance, manliness, courage… One of my aunts was a musician; she married a very brutal man who made her unhappy. She let herself die of hunger, playing the piano all through the night. It was hearing her play night after night, until she died, and finding her music afterward, which drew me to the piano. Bach, Beethoven, the best, which at that time were very little known in such far-off ranches. The schools of music were only frequented by girls. It was thought to be an effeminate art. I had to give up going there and study alone, because the girls laughed at me. Although I was so big, and so rough in many ways, loved hunting, fighting, horseback riding, I loved the piano above everything else… The mountain man’s obsession is to get a glimpse of the sea. I never forgot my first sight of the ocean. The train arrived at four in the morning. I was dazzled, deeply moved. Even today when I read the Odyssey it is with the fascination of the mountain man for the sea, of the snow man for warm climates, of the dark, intense Indian for the Greek light and mellowness. And it is that which draws me to you, too, for you are the tropics, you have the sun in you, and the softness, and the clarity…”

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

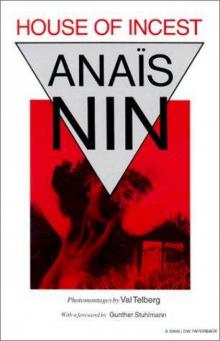

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest