Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 Read online

Page 2

She was without discrimination about men, so that I found it difficult to go out with her and her friends. I preferred solitude. Acapulco was a beautiful background for her. Her skin was naturally tan. She was like a native and in harmony with her surroundings.

She met Orozco, Diego Rivera, and Siqueiros in New York when taking a master's in fine arts at Teachers College, Columbia. They invited her to work on murals in Mexico. There she met her second husband, who was a powerful industrialist. Now she was married to a composer, Conlon Nancarrow.

She was natural, talkative, fluent, and always effervescent.

When I met her she had become so international, so well traveled, so multilingual, so at ease with all kinds of people, that no one could imagine her childhood, her origin.

Her dream was to build a house in Acapulco and stay there.

The past is dissolving in the intensity of Acapulco. The intense sunlight annihilates thought, and the animation of the crowd, the colors, the smiles, the dances at night, the gaiety of the beach close the eyes of memory. Freedom from the past comes from associating with unfamiliar objects; none of them possesses any evocative power. The hammock, the spectacles of sunrise and sunset, the exotic flowers, are all unfamiliar. From the moment I open my eyes I am in a new world. The colors are all hot and brilliant. Breakfast is a tray of fruit never tasted before, papaya and mangoes. All day long there is not a single familiar object to carry me back into the past.

The first human being I see in the morning is the gardener. I can see him at work through the half-shut bamboo blinds. He is raking the pebbles and the sand, not as if he were eager to terminate the task, but as if raking pebbles and sand were a most pleasurable occupation and he wants to prolong the enjoyment. Now and then he stops to talk to a lonely little girl who skips rope and asks him questions which he answers patiently.

Groups form in the evening on the terrace to plan whether to dance all night at the Americas Hotel, where there is a jazz band, or take an excursion to a little-known cove where one can swim nude and where the waves are phosphorescent. New groups form every night, new arrivals, new introductions.

The pool of the Mirador is another gathering place for those who love the night and a quiet swim before sleep.

Because someone had plunged into it from one of the rooms of the hotel late at night and drowned, the pool was now locked, but we all slipped over the gate. I heard one woman say to her young man: "Will you float me home?"

Tonight I met a young man who hitchhiked all the way from Chicago and was picked up by the patron of the hotel and given secretarial work. His candor, bewilderment, and wonder at everything rejuvenates the most indifferent visitors already accustomed to the beauty. I call him Christmas, because he said his first love-making was as wonderful as a Christmas tree. Annette's freedom fascinated him. She bubbles, her talk is like the foam of the sea, her laughter dispels all concerns.

The doctor and I sit in a hand-carved canoe. The pressure of the hand on the knife made uneven indentations in the scooped-out tree trunk which catch the light like the scallops of a sea shell. The sun on the rim of the carvings and the shadows within their valleys give the canoe a stippled surface like that of an Impressionist painting. As it moves forward in the water it seems like a multitude of changeable colors in motion.

The canoe was once painted in laundry blue. The blue has faded and has become like the smoky blue of old Mayan murals, a blue which man cannot create, only time.

The fisherman is paddling quietly through the varied colors of the lagoon water, colors which range from the dark sepia of the red-earth bottom to silver-gray when the colors of the vegetation triumph over the red earth, to gold when the sun conquers them both, to purple in the shadows. He paddles with one arm. His other arm was blown off when he was a young fisherman of seventeen first learning the use of dynamite sticks for fishing.

The mangrove trees in the lagoon show their naked roots, as though on stilts, an intricate maze of the silver roots as fluent below as they are interlaced above. The overhanging branches cast shadows before the bow of the canoe so dense that I can hardly believe they will open and divide to let us through. The roots look like a grasping giant hand, extending fingers into the water to hold on to a treacherous moving soil, fingers which in turn give birth to smaller fingers seeking a hold on the bank.

Emerald sprays and fronds project from a mass of wasps' nests, of pendant vines and lianas. Above my head the branches form metallic green parabolas and enameled pennants, while the canoe and my body accomplish the magical feat of cutting through the roots and dense tangles.

The canoe undulates the aquatic plants that bear long plumes and travels through reflections of the clouds.

The snowy herons and the shell-pink flamingos meditate upon one leg like yogis of the animal world. Iguanas slither away, and parrots become hysterically gay.

Now and then I see a single habitation by the water's edge, an ephemeral hut of palm leaves wading on frail stilts, and a canoe tied to a toy-sized jetty. Before each hut stands a smiling woman and several naked children.

I see the mud tracks of a crocodile. The scaly colors of the skin of the iguanas is so exactly like the ashen roots and tree trunks that you cannot spot them until they move. They lie as still as stones in the sun, as if petrified, and their tough, wrinkled skin looks thousands of years old.

***

A flowing journey.

I had a recurrent dream always of a boat, sometimes small, sometimes large, but invariably caught in a waterless place, in a street, in a city, in a jungle or a desert. When it was large it appeared in city streets, and the deck reached to the upper windows of houses. I was always in this boat and aware it could not sail unless I pushed it, so I would get off and seek to push it along so it might move and finally reach water. The effort of pushing the boat along the street was immense and I never accomplished my aim. Whether I pushed it along cobblestones or over asphalt, it moved very little, and no matter how much I strained I always felt I could never reach the sea.

Today on the lagoon, I felt that my dream of pushing the boat would never recur. I have attained a state of being which is effortless, a flowing journey. I am in harmony with nature, with the rhythm of the natives, and this is created not only by the presence of water (I experienced this feeling before in the houseboat on the Seine) but also by the fusion of my body with nature, the healing separation from our dissonant and harsh Western life.

I had read that certain Egyptian rulers believed that after death they would join a celestial caravan in an eternal journey toward the sun and the moon. Archaeologists had unearthed two wooden barques buried in a royal tomb which they recognized from ancient texts and mural paintings. There was a lunar barque for the night journey to the moon and a solar barque for the day journey to the sun.

In dreams I perpetuated such journeys in solar barques. There were always two. One buried in limestone and unable to float on the waterless routes of anxiety, the other flowing continuously with life. The static one made the repetitive journey of memories, and the flowing one proceeded into endless discoveries.

I am now in my flowing journey.

There is a quality in this place which does not come altogether from its beauty. Is it the softness of the air which relaxes body and soul? Is it the continuity of music which makes the blood rhythms pulsate?

I let my hand drop in the waters of the lagoon, to feel the gliding, to assure myself of the union with a living current, as if touching the flow of life within me, this life which blooms only in places where the life force is vital and expansive: Morocco, Mexico.

***

I took my laundry to a woman who lives down the road, recommended by the hotel. I came to a shack without a front wall, with a dirt floor. The woman was ironing with an iron which had to be heated over a coal stove. Her children were playing naked on the dirt. Behind her, on a steep hill, was the laundry drying over bushes. There was no running water. She washed the clothes at the

river or at the village trough. But she was singing, full-throated, fluid, strong, like the song of the tropical birds in the trees above her. The song rose above the steam of the iron, above the dirty children, above the backyard, above the visitor standing at the front of the house with a bundle of summer dresses.

Sunday night the local people come to dance on the terrace next to the hotel. There is a native band. They only stop to watch the divers, or to take a walk down the steep descent to where the sea leaps and foams against the rocks.

I dance with the young men of the town. Some are future divers, dreaming nf riches. Others dream of becoming guides, chauffeurs, bus drivers. One of the divers was "adopted" by a wealthy American woman. She paid to get him several new gold teeth, of which Mexican boys are very proud. This gave him an idea. Every new batch of tourists provided at least one godmother willing to pay for a gold tooth. The diver learned to take them out and reappear with missing teeth, and each godmother, compassionate for a young man with missing teeth, paid, and with each operation the boy made a little money from the sale of the gold.

An American was put in jail because he had no papers. The tourists were invited to visit him, to plead for him. They wrote to the American Consulate. But he stayed in jail, and he told whoever came to see him that a tip of fifty dollars to his jailer would get him out. The fifty dollars were paid, and he was out for a few days and then in jail again, awaiting new visitors. We saw the jailer and his victim celebrating at the Spanish restaurant on the square.

Once in a while I like to be alone. I walk down the hill to the square, which is full of interest. It is the heart of the town. The church opens its doors on one side, the movie house on the other, and in between, the square is lined with cafés and restaurants with their tables on the sidewalks. In the center is a small bandstand, surrounded by a park with old umbrella trees and plenty of benches.

On the benches sit enraptured young lovers, tired hobos, old men reading their newspapers. Because of the scraps of crackers and candies on the ground, the birds are concentrated here, and they fill the trees with merry chatter and songs. There is also a circle of vendors sitting on the sidewalks with their baskets full of candied fruit, colored fruit drinks, gold jewelry they learned to make from the Moors, delicate filigree work. Old ladies in black shawls walk quietly in and out of the church, children beg merrily, marimba players settle in front of each café and play for tips.

The flow of beggars is endless. A few change their handicaps. When they tire of portraying blindness they appear with wooden legs, concealing their good legs under them. The genuine ones are terrifying, like nightmare figures: A child shriveled and shrunken, lying on a board with wheels which he pushes with his withered hands; an old woman so twisted that she resembles the roots of very ancient trees; many of them sightless, with festering sores in place of eyes. They all refuse Dr. Hernandez's help. They do not want to be locked in hospitals. They want to remain a part of the religious processions, the fireworks, the funerals, the weddings, band concerts, and the display of foreigners with their eccentric costumes.

But custom will not allow me to sit alone in a restaurant. Not Mexican custom. A man came and threw some money on my table, and sat down. The patron of the restaurant had to explain that foreign women went about alone and it did not mean they were prostitutes.

Another time a comedy of errors. A young American student was stranded. He had been hitchhiking and no one was driving to Mexico City. He had no place to stay. He had spent the evening with two young women I knew, but they had no room for him. I offered him the hammock on my terrace. He accepted. In the morning, when I stepped out he was still asleep. While I was having breakfast he went into my room to shave and bathe. The maid found him there and reported to the "patron" who gave me a lecture on morality: "None of those American ways will be tolerated in my hotel."

One day we decided to visit the jungle ranchita of Hatcher, an American engineer who had married a local Mexican woman and was attempting to achieve the American dream of "going native." His place was near San Luis, north of Acapulco, on the road to Zihuatanejo. The road was dusty and difficult, but we had the feeling of penetrating into a wilder, less explored part of Mexico. Villages were few and far between; we met rancheros on horseback, in their white suits and ponchos and enormous hats, carrying their machetes rigidly. We saw women washing clothes by the river. Some huts were without walls, just a web of branches supported by four slender tree trunks. Babies lay in hammocks.

The river beyond San Luis was wide, and cars had to be ferried. We waited for the ferry, a flat raft made of logs tied together. The men pushed it along with long bamboo poles.

When we left the raft we started a journey into the jungle. A dust road with just enough room for the car. Cactus and banana leaves scraped our faces. When we were deep in the forest and seemingly far from any village, we saw a young man waiting for a ride. He carried a heavy, small doctor's bag.

"I'm Dr. Palas," he said. "Will you give me a ride?"

When he was settled he explained: "I have just delivered a child. I'm stationed at Zihuatanejo."

He was carrying a French novel like the ones Dr. Hernandez must have carried at his age, for they all studied medicine in France. Was he devoted to his patients? The Mexican medical plan rules that interns must work a year in a village where there is no doctor. This was the way Dr. Hernandez first came to Acapulco when it was a fishing village.

When we reached his village, where we were to spend the night, we had rooms across from his bungalow. A workman came in the middle of the night and called out to him, pleading and begging: "I have a splinter in my eye." But Dr. Palas did not come out. The poor workman stayed until dawn, and then the doctor deigned to come out and attend to him. I was shocked by his callousness. We went off without saying goodbye to him. I remembered his cynical words: "I have a year of this to endure."

Hatcher's place was deep in the jungle on a hill overlooking the sea. On a small open space he had built a roof on posts, with only one wall in the back. The cooking was done out of doors. A Mexican woman was bending over her washing. She only came to greet us when Hatcher called her. She was small and heavy, and sad-faced, but she gave Hatcher a caressing look and a brilliant smile. She showed only a conscious politeness to us.

"You must excuse us, the place is not finished yet. My husband works alone and he has a lot to do."

"Bring the coffee, Maria." She left us sitting around a table on the terrace, staring at an unbelievable stretch of white sand, dazzling white foam spraying a gigantic, sprawling vegetation which grew to the very edge of the sand. Birds sang deliriously, and monkeys clowned in the trees. The colors seemed purer and clearer, like those of a fresh place never inhabited before.

Maria came with coffee in a Thermos.

Hatcher said: "She is a most marvelous wife."

"And he is a wonderful husband," said Maria. "Mexican husbands never go around telling everyone they are married. He goes about buying presents for his wife, talking about his wife."

Turning to me she said in a low voice: "I don't know why he loves me. I am so short and squatty. He was once married to a tall, slim American woman like you. He never talks about her. I worked for him at first. I was his secretary. We are going to build a beautiful place here. This is only the beginning."

They had their bedroom in the back, protected by curtains. Visitors slept in hammocks on the terrace.

We took a walk to the beach. The flowers which opened their velvety faces toward us were so eloquent they seemed about to speak. The sand did not seem like sand, but like powdered glass which reflected the light.

The sea folded its layers around me, touching my legs, my hips, my breasts like a liquid sculptor with warm hands.

When I came out of the sea, I felt reborn. I longed for this simplified life. Cooking over a wood fire, sleeping out of doors in a hammock, with only a Mexican blanket. I longed for naked feet in sandals, the freedom of the body in summer clothes, hai

r washed by the sea.

When we returned Maria had set the table. The lights were weak bulbs hanging from wires. The generator made a loud throbbing. But the trees were full of fireflies, crickets, and pungent odors. There was a natural pool fed by mountain water where we could wash off the salt from the sea.

After a dinner of fish and black beans, Hatcher offered to show us the rest of his house. Behind the wall there was a storage room of which he was immensely proud. It was enormous, as large as the house itself, with shelves reaching to the ceiling. There was in it every brand of canned food, medicines, tools, hunting guns, fishing equipment, garden tools, vitamins, seeds. He reveled in the completeness of it. "What would you like? Cling peaches? Asparagus? Quinine? Magazines? Newspapers? I even have a pair of crutches in case of need. I have ether, and instruments for surgery."

I felt immensely tired and depressed. I lay in my hammock pondering why I was so disappointed. I had imagined Hatcher free. I admired him as a man who had won independence from our culture and could live like a native, a simplified existence with few needs. And here he demonstrated complete dependence on complex and artificial products. America the mother and father had been transported into a supply shed, bottled and canned. He was not able to live here without possessions, with fresh fish and fruit and vegetables in abundance, with cow's milk and the products of hunting.

His fears made me question: was there no open road, simple, clear, unique? Could I live a new life here in Mexico, free of all that had wounded me in the past, and free of dependency? Hatcher was not free of his bitterness about his first marriage, nor free of America. He was not free of the past.

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

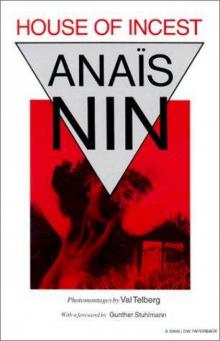

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest