Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 Read online

Page 4

I slipped it under my pillow like a sweet reward.

I had talked about my printing press, and the students dug out an old press which was lying inactive in the garage, and began printing poetry.

A few days later I received my first letter from Jim Herlihy and a story.

***

New York on my birthday, February si.

I had told my friends about the way Mexicans celebrate birthdays. How they rise at dawn and come to serenade one, so you will be born to music and the dawn. My poor New York friends got up before dawn on a bitter cold morning and rang my bell to serenade me.

In New York there were work and duties, but I was detached from them. I accepted a lecture at Houston, Texas. Signing books in a bookstore, being feted with a dinner, seeing a person I would like to know better, like someone you see out of a train window, and wistful that it should all be so swift and superficial. What do you leave of yourself? What do I remember? It passes too swiftly.

I return to Los Angeles for another book-signing party.

Los Angeles is not as deeply natural or joyous as Mexico, but the white houses, the palm trees and the sun give a feeling of lightness; people are tanned, they seem carefree, they prefer the beach to an exhibition, the beach to a concert, the beach to a theater. The cars shine and carry surfboards on their roofs. Or the drivers ride in bathing suits, with the top down, hair flying. There are parts of the beach which are deserted, rocks to sunbathe on. I am awakened by the singing of the mocking birds. They sing at night like Keats' nightingale. It is a forest of billboards, each bigger and louder than the next. It is Nathanael West's Hollywood, a fair, grotesque, vaudeville, a grade B film. The people on Hollywood Boulevard dress as though they bought their clothes in a thrift shop, a fur coat and sandals, slacks and gold shoes, satin waists and sport skirts. Dyed hair tired of being dyed. They live in boardinghouses, awaiting roles, jobs, stardom.

[Spring, 1948]

I met Kenneth Anger in San Francisco. He is a very handsome young man with Latin eyes and dark hair (he has Cuban blood). He wanted to meet me because of Under a Glass Bell and spent his whole week's salary on taking me to an expensive Russian restaurant, where we ate flaming shish kebab. It was the ritual he thought appropriate for the author of Under a Glass Bell, and when I found out how poor he was I made vain efforts to make him see the real Anaïs who does not like deluxe restaurants.

At someone's house I was shown his film Fireworks. The sadism and violence revolted me, but the film has power and is artistically perfect. It has a nightmare quality. Everyone had mixed feelings, horror and recognition of Kenneth Anger's talent.

The films of Curtis Harrington are different. They are entirely surrealistic, suggesting the dream, mysteries, and metamorphosis, with a touch of magic in the camera work. What he does with natural settings, his friends as actors, is imaginative.

In different ways, both promise to become unusual film makers.

I write every day.

I gave a reading at a small theater.

I go to the beach with Curtis Harrington, Paul Mathiesen, Kenneth Anger.

We talk about films. They are educating me in the history of films, passing on to me the knowledge they gained in UCLA film-making classes. Leonard W. is on his way back from Korea and scolds me because my letters have become impersonal. I answer that is an art I learned from him. Two years of training and I passed with honors.

Clippings and reviews of Under a Glass Bell. Not one line of understanding.

Visit to San Francisco. Ruth Witt Diamant invited me to read at San Francisco State College. Her home is the guesthouse of the poets she invites to her Poetry Center: Dylan Thomas, W. H. Auden, Kenneth Patchen, Harold Norse, Kenneth Rexroth, et cetera. She is warm and witty and hospitable, and devoted to poetry. She owns some of Janko Varda's collages.

***

The deep life runs securely like a river and the rest is adornment. I no longer fear the shallowness of my father when I give time to take care of my body, lie in the sun, swim, learn to drive a car.

In Denver, during my trip out West, I met Reginald Pole. He is an actor, dramatist, a stage director, a composer. He is famous as a Shakespearean actor. At the time he was directing his own play, Malice Toward None, a dramatization of Abraham Lincoln's last years in which he also played the title role.

He was born in Japan, where his father was continuing the work of his grandfather, William Pole, who was awarded the third order of the Rising Sun for his work in establishing Japan's railroad system.

He did not talk about Japan, but he talked a great deal about his life at King's College, Cambridge University, from which he graduated. He was trained in theater by his uncle, William Poel, [the original spelling of the name was forbidden for professional use], the most famous producer of Shakespeare since James Burbage of the old Globe Theatre. He talked about his friendship with Rupert Brooke, and their founding of the Marlowe Dramatic Society to produce plays at Cambridge. He knew the group which was later to become the famous Bloomsbury circle. He would have fitted in with Virginia Woolf, Thomas Hardy, John Cowper Powys. But he was plagued with asthma, which drove him out of England.

He had intended to join Rupert Brooke in Tahiti. He stayed in Tahiti long enough to engage in a romance with a princess of the reigning family. He read me her letters in French. He was deeply immersed in the beauty of Tahiti, as he described it in his autobiographical novel, and he was, according to his English upbringing, discreet about the romance. But it was as easy to imagine the princess in love with a romantic-looking young Englishman, as handsome as Aldous Huxley and Rupert Brooke, who courted her with poetry, as it was to imagine him being in love with a Tahitian princess. Reginald must have seen Tahiti as Rupert Brooke did, though he may not have been as playful and exuberant.

Her parents became alarmed that the romance would become serious and interfere with the marriage planned for her for the benefit of royal succession. Reginald never told me how they informed him of their wishes that he should continue on his journey. Whether it was done with the courtly tact of the Tahitians, or more directly, I never knew. Nor did Reginald's natural reticence permit him to inform us of details. But a note from the widow of Robert Louis Stevenson asking him to come and visit her in a most wonderful place called Palm Springs, California, determined his leaving. He came away with a conch shell, which he had learned to blow as the Tahitians do, to call everyone to the feasts.

Once in Los Angeles he had to find out where Palm Springs was. The train went as far as Whitewater, and then, as he was told by an old Indian, he must wait for the buckboard. "How long?" he asked. "Oh, it might be hours, it might be days. But wait there. It will come." The buckboard did come at last, and he found himself in the desert.

There were only two houses in Palm Springs, one now the Desert Inn, where Mrs. Kaufman had set up tents for tubercular patients, and the other occupied by Dr. White, a woman who collected collie dogs.

Reginald met Mrs. Stevenson, who was ill. He was entranced by the desert.

In Los Angeles he produced Shakespeare, Greek dramas, Ibsen, with the collaboration of Lloyd Wright and Lawrence Tibbett.

In New York in the early twenties, he directed and acted in his own version of Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov and The Idiot with Estelle Winwood and Boris Karloff. Later he acted the ghost in John Barrymore's Hamlet. His American-Indian ballet was performed by Ernst von Dohninyi with the New York State Symphony, and at the Metropolitan Opera House, and in Boston in 1925.

He married an actress, Helen Taggart (later Mrs. Lloyd Wright). They built the third house in Palm Springs.

He shared with his friend and mentor, John Cowper Powys, the gift for lecturing with an actor's sense of drama. Powys wrote that they both had the dramatic quality of born actors.

He played Christ in the yearly performances of the Pilgrimage Play in the Hollywood Hills. He gave lectures on:

The Emergence of Woman in the Modern World

The

Spiritual Foundation of Art

The Meaning of Beauty

Greek Drama

The Value of Repose

Beethoven and the Heroic Soul

Idealism and America

His erudition was vast. He was an unusually handsome man, tall, very thin, with the long lean face of the Anglo-Saxon, pale-blue eyes under bushy eyebrows, refined features. My first impression of him was: this is the father I would have liked to have.

He was only in his late fifties, but he lay down on the couch after a performance as if he were about to die. His eyes were closed, his voice was a whisper. When the conversation touched upon a subject which interested i›:m, he suddenly recovered his energy, his voice became the resonant actor's voice, his gestures vehement and emphatic. A few minutes later he would lie back again as if the effort had drained him.

It seemed appropriate that Reginald should have acted the ghost in Hamlet. By the time I met him, I was seeing a ghost of himself. The underlying self-destruction which was corroding his marvelous gifts was already at work.

He preferred to sit and talk. He would have fitted in the café life of Europe, to discuss art and philosophy, the theater and literature.

His passion for the theater and literature did not rule his life. What ruled his life was an abnormal preoccupation with his body, his ambulant anxiety which made him move from one dismal hotel to another, sleep all day in darkened rooms, prowl at night when his friends were asleep and could not see him.

He comes to visit me in Los Angeles, late in the evening, and wants to talk most of the night, which means I cannot work the next day because I do my best work in the morning.

I grew to dread his inactivity and need of talk. It was as if he sought constantly to fulfill an unfulfillable hunger, which was a return to the passivity of the child and a mother's care. He sought the mother throughout his life. There was always a woman of his age willing to play the role until he wearied them with his demands and they were replaced by another.

But if the mother made the slightest demand on him, such as wanting him to accompany her to a concert or an exhibit, he pleaded illness.

Strange destiny which makes one encounter the same figures many times. I purposely described in full the fascination of Reginald and the danger he presented. He was Helba again. They are always about to die, always using their dramatic power to make their slightest illness a major tragedy, always dramatizing their need, to engage others into serving them, waiting on them, helping them. They had the same way of skillfully working on the compassion of others.

But karma is evolution. I am not the same woman who was helpless and victimized by Helba's demands. I admire Reginald, but I know exactly what his demands would do to a human being. Unknowingly he has the most destructive effect on those around him.

J. C. Flugel [in Man, Morals and Society: A Psychoanalytical Study] has something interesting to say about the artist, and distance from reality:

The artist can neither be too distant because the myth distorts reality, nor too close to it for then its uninteresting and irrelevant details also distort the essential outline which gives us the quintessence of reality. We have to face the fact that for many adults, and for still more children, the frustrations and conflicts aroused by reality are often more than can be born, and that at least an occasional retreat from reality into some form of artistic thinking [in spite of all the dangers of such wishful thinking, to which Flugel gives a whole chapter] is almost inevitable, even if only for the purpose of backtracking to better leap forward.

Reginald Pole took me to meet Charlie Chaplin at his home. Chaplin is an enchanting storyteller, acting out each story. He had just come back from Bali, and he was miming everything he saw. His face is pink and healthy, and he stands in the middle of the room performing while Oona sits quietly and unobtrusively in a corner. He was bitter about America's treatment of him, but only spoke briefly about that.

When I read Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse, I felt it was a description of Reginald. The self-created loneliness which nothing can assuage, the self-enclosed walls separating him from human beings. One can only feel compassion for that incurable illness of the soul.

I wanted to say: "Reginald, come out of your darkened rooms. Come out in the light and the sun of day. Live with the friends who love you."

But his message seemed to be: "Come and die with me. Keep me company in my death. Hold my hand while I lie in a state of nonexistence."

***

Reginald takes me to meet Cornelia Runyon. She looks as the Queen of England should look. She is suntanned from living at the beach and her sculpture studio is on the terrace, out of doors. Her house is beautiful, sits high on the rocks above the sea at Zuma Beach, north of Malibu. In the living room her sculptures of semiprecious stones are standing against the window, and so the sun makes them incandescent.

She gives the impression that she is one of her own sculptures. Her beautiful deeply tanned face is molded with finesse and strength to express wit and liveliness and something undefinably enduring, eternal as stone. Hers is a beauty sculptured by intelligence and quality. There is a harmony between her appearance, her house high above the beach, and her work, which looks like a part of the sea, the rocks, and the sky. It was here that she started late in life to work with stones which she found on the beach. She began with stone because she felt it more alive than clay. Later she discovered semiprecious stones in the desert and began to work with blue calcite, howlite, rose quartz, aventurine, jade, jasper, basalt, obsidian, malachite, and granite.

From the first she had an essentially feminine attitude toward her material. She began with a respect for what the sea or the earth had already begun to form in the stones. She contemplated and meditated over them, permitting them to reveal the inherent patterns they suggested. She never imposed her own will over the image tentatively begun by nature. She discovered and completed the image so that it became visible and clear. She assisted the birth of chaotic masses into recognizable forms. She watched, mused, observed, to allow the potential in the stone to reveal its hidden qualities, color, texture, bulk, half-born animal or man. She carved with care for what was already there, so that every head or animal remained simultaneously at one with nature, not torn away while yet acquiring a personality, an individual character our eyes can identify.

In this way, her way, what came through was not some abstraction torn away from its basic roots, its textures, its organic growth; but something her tender, maternal, intuitive hands allowed to grow organically, without losing its connection with the earth or sea. It is necessary to stress this, because at this time critics favored pure abstraction and advised her to impose her will on difficult materials. Her work, I believe, is the opposite of an act of will. It is an act of creativity which remains rooted in nature, more like an act of giving birth. It reminds one of the ancient myth about the image asleep in the block of marble until it is carefully disengaged by the sculptor. The sculptor must himself feel that he is not so much inventing or shaping the curve of a breast or shoulder as delivering the image from its prison.

I believe this myth fits the attitude of Cornelia Runyon toward her work. The ego is absent. She writes humbly: "I am so grateful for those twenty years with stone," as if the stone had given itself to her, as if there had been a collaboration between them. And again: "Many artists came to see and said to me: 'You must impose your will.' I listened but went on my own way, the way I found most happy, to feel the content of the stones and listen closely to their richly mysterious messages."

Because she revealed the forms, moods, messages of nature without tampering with them, they retained their intense, vivid life and their mystery. Her lack of egocentricity is like that of cathedral builders who refused to sign their designs. Everything lies asleep until she touches it like some intuitive mother, and then it discloses its inner life which she has liberated.The Eagle reveals his hesitations before his first flight, her Seal is graceful and playful in spite of h

is shining wet density.

She tells of the days when she loved swimming under water and how she saw fish moving around her. She found this shining fish in calcite and he seems to be glistening with water. She utilizes the dimensions of the stone's own colors, transparencies, and inner fire. She integrates its veins, stratas, contours, and textures. Her Head of a Woman in rose quartz has the incandescence of real flesh illumined with poetic radiance. Her Cathedral is a quintessence of light and lyrical aspirations. Her Sleeping Bird is not only asleep, he shivers with dreams. Another Head has as many facets as the Goddess Shiva has arms and legs in Hindu mythology. Her Snake flips its tail with arrogance, and her Buffalo butts its head with delight. Her Turtle clings to his carapace but scans the horizons. Her Walrus is a gracious comedian and the Creeping Creature may be born of a vision into the future.

Cornelia Runyon captures the vital emotional existence of man and animal in the living mobility and fluidity of the forms not entirely separated from the elements in which they were born. Here is no cold abstraction or mathematical equation but the eloquence of moods, the human messages from mute flesh: I fly, I crawl, I weep, I laugh, I swim, I grow, I fall, I need, I want, I follow, I break, I sink, I love, I exist.

She was born in 1887 in New York, and had little formal training, a few short months at the Art Students League. But she is a descendant of the men who built and sailed the great clipper ships out of Boston. Perhaps for this reason she chose the challenge of the hardest stones, the least tractable. She accepted the difficulty of giving subtle life to such unyielding masses.

A child of seven returning from a visit to Cornelia, falling asleep on the way home, murmured: "It was so alive-ing."

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

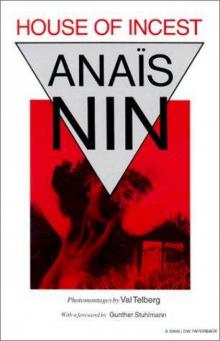

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest