The Four-Chambered Heart Read online

Page 4

She sat beside him by the fire, partaking of this primitive bonfire. A ritual to usher in a new life.

If he continued to destroy malevolently, they might reach a kind of desert island, a final possession of each other. And at times this absolute which Rango demanded, this peeling away of all externals to carve a single figure of man and woman joined together, appeared to her as a desirable thing, perhaps as a final, irrevocable end to all the fevers and restlessness of love, as a finite union. Perhaps a perfect union existed for lovers willing to destroy the world around them. Rango believed the seed of destruction lay in the world around them, as for example in these books which revealed to Rango too blatantly the difference between their two minds.

To fuse then, it was, at least for Rango, necessary to destroy the differences.

Let them burn the past then, which he considered a threat to their union.

He was driving the image of Paul into another chamber of her heart, an isolated chamber without communicating passage into the one inhabited by Rango. A place in some obscure recess, where flows eternal love, in a realm so different from the one inhabited by Rango that they would never meet or collide, in these vast cities of the interior.

“The heart…is an organ…consisting of four chambers… A wall separates the chambers on the left from those on the right and no direct communication is possible between them…”

Paul’s image was pursued and hid in the chamber of gentleness, as Rango drove it away, with his holocaust of the books they had read together.

(Paul, Paul, this is the claim you never made, the fervor you never showed. You were so cool and light, so elusive, and I never felt you encircling me and claiming possession. Rango is saying all the words I had wanted to hear you say. You never came close to me, even while taking me. You took me as men take foreign women in distant countries whose language they cannot speak. You took me in silence and strangeness…)

When Rango fell asleep, when the aphrodisiac lantern had burnt out its oil, Djuna still lay awake, shaken by the echoes of his violence, and by the discovery that Rango’s confidence would have to be reconstructed each day anew, that none of these maladies of the soul were curable by love or devotion, that the evil lay at the roots, and that those who threw themselves into palliating the obvious symptoms assumed an endless task, a task without hope of cure.

The word most often on his lips was trouble.

He broke the glass, he spilled the wine, he burnt the table with cigarettes, he drank the wine which dissolved his will, he talked away his plans, he tore his pockets, he lost s buttons, he broke his combs.

He would say: “I’ll paint the door. I will bring oil for the lantern. I will repair the leak on the roof.” And months passed: the door remained unpainted, the leak unrepaired, the lantern without oil.

He would say: “I would give my life for a few months of fulfillment, of achievement, of something I could be proud of.”

And then he would drink a little more red wine, light another cigarette. His arms would fall at his side; he would lie down beside her and make love to her.

When they entered a shop, she saw a padlock which they needed for the trap door and said: “Let’s buy it.”

“No,” said Rango, “I have seen one cheaper elsewhere.”

She desisted. And the next day she said: “I’m going near the place, where you said they sold cheap padlocks. Tell me where it is and I’ll get it.”

“No,” said Rango. “I’m going there today. I’ll get it.” Weeks passed, months passed, and their belongings kept disappearing because there was no padlock on the trap door.

No child was being created in the womb of their love, no child, but so many broken promises, each day an aborted wish, a lost object, a misplaced unread book, cluttering the room like an attic with discarded possessions.

Rango only wanted to kiss her wildly, to talk vehemently, to drink abundantly, and to sleep late in the mornings.

His body was in a fever always, his eyes ablaze, as if at dawn he were going to don a heavy steel armor and go on a crusade like the lover of the myths.

The crusade was the café.

Djuna wanted to laugh, and forget his words, but he did not allow her to laugh or to forget. He insisted that she retain this image of himself created in his talks at night, the image of his intentions and aspirations. Every day he handed her anew a spider web of fantasies, and he wanted her to make a sail of it and sail their barge to a port of greatness.

She was not allowed to laugh. When at times she was tempted to surrender this fantasy, to accept the Rango who created nothing, and said playfully: “When I first met you, you wanted to be a hobo. Let me be a hobo’s wife,” then Rango would frown severely and remind her of a more austere destiny, reproaching her for surrendering and diminishing his aims. He was unyielding in his desire that she should remind him of his promises to himself and to her.

This insistence on his dream of another Rango touched her compassion. She was deceived by his words and his ideal of himself. He had appointed her not only guardian angel, but a reminder of his ideals.

She would have liked at times to descend with him into more humanly accessible regions, into a carefree world. She envied him his reckl hours at the café, his joyous friendships, his former life with the gypsies, his careless adventures. The night he and his bar companions stole a rowboat and rowed up the Seine singing, looking for suicides to rescue. His awakenings sometimes in far-off benches in unknown quarters of the city. His long conversations with strangers at dawn far from Paris, in some truck which had given him a ride. But she was not allowed into this world with him.

Her presence had awakened in him a man suddenly whipped by his earlier ideals, whose lost manhood wanted to assert itself in action. With his conquest of Djuna he felt he had recaptured his early self before his disintegration, since he had recaptured his first ideal of woman, the one he had not attained the first time, the one he had completely relinquished in his marriage to Zora—Zora, the very opposite of what he had first dreamed.

What a long detour he had taken by his choice of Zora, who had led him into nomadism, into chaos and destruction.

But in this new love lay the possibility of a new world, the world he had first intended to reach and had missed, had failed to reach with Zora.

Sometimes he would say: “Is it possible that a year ago I was just a bohemian?”

She had unwittingly touched the springs of his true nature: his pride, his need of leadership, his early ambition to play an important role in history.

There were times when Djuna felt, not that his past life had corrupted him—because in spite of his anarchy, his destructiveness, the core of him had remained human and pure—but that perhaps the springs in him had been broken by the tumultuous course of his life, the springs of his will.

How much could love accomplish: it might extract from his body the poisons of failure and bitterness, of betrayals and humiliations, but could it repair a broken spring, broken by years and years of dissolution and surrenders?

Love for the uncorrupted, the intact, the basic goodness of another, could give a softness to the air, a caressing sway to the trees, a joyousness to the fountains, could banish sadness, could produce all the symptoms of rebirth…

He was like nature, good, wild, and sometimes cruel. He had all the moods of nature: beauty, timidity, violence, and tenderness.

Nature was chaos.

“Way up into the mountains,” Rango would begin again, as if he were continuing to tell her stories of the past which he loved, never of the past of which he was ashamed, “on a mountain twice as high as Mont Blanc, there is a small lake inside of a bower of black volcanic rocks polished like black marble, in the middle of eternal snow peaks. The Indians went up to visit it, to see the mirages. What I saw in the lake was a tropical scene, richly tropical, palms and fruits and flowers. You are that to me, an oasis. You drug me and at the same time you give me strength.”

(The drug of love was no escape, for in its coils lie latent dreams of greatness which awaken when men and women fecundate each oter deeply. Something is always born of man and woman lying together and exchanging the essences of their lives. Some seed is always carried and opened in the soil of passion. The fumes of desire are the womb of man’s birth and often in the drunkenness of caresses history is made, and science, and philosophy. For a woman, as she sews, cooks, embraces, covers, warms, also dreams that the man taking her will be more than a man, will be the mythological figure of her dreams, the hero, the discoverer, the builder… Unless she is the anonymous whore, no man enters woman with impunity, for where the seed of man and woman mingle, within the drops of blood exchanged, the changes that take place are the same as those of great flowing rivers of inheritance, which carry traits of character from father to son to grandson, traits of character as well as physical traits. Memories of experience are transmitted by the same cells which repeated the design of a nose, a hand, the tone of a voice, the color of an eye. These great flowing rivers of inheritance transmitted traits and carried dreams from port to port until fulfillment, and gave birth to selves never born before… No man or woman knows what will be born in the darkness of their intermingling; so much besides children, so many invisible births, exchanges of soul and character, blossoming of unknown selves, liberation of hidden treasures, buried fantasies…)

There was this difference between them: that when these thoughts floated up to the surface of Djuna’s consciousness, she could not communicate them to Rango. He laughed at her. “Mystic nonsense,” he said.

As Rango chopped wood, lighted the fire, fetched water from the fountain one day with energy and ebullience, smiling a smile of absolute faith and pleasure, then Djuna felt: wonderful things will be born.

But the next day he sat in the café and laughed like a rogue, and when Djuna passed she was confronted with another Rango, a Rango who stood at the bar with the bravado of the drunk, laughing with his head thrown back and his eyes closed, forgetting her, forgetting Zora, forgetting politics and history, forgetting rent, marketing, obligations, appointments, friends, doctors, medicines, pleasures, the city, his past, his future, his present self, in a temporary amnesia, which left him the next day depressed, inert, poisoned with his own angers at himself, angry with the world, angry with the sky, the barge, the books, angry with everything.

And the third day another Rango, turbulent, erratic, dark, like Heathcliff, said Djuna, destroying everything. That was the day that followed the bouts of drinking: a quarrel with Zora, a fight with the watchman. Sometimes he came back with his face hurt by a brawl at the café. His hands shook. His eyes glazed, with a yellow tinge. Djuna would turn her face away from his breath, but his warm, his deep voice would bring her face back saying: “I’m in trouble, bad trouble…”

On windy nights the shutters beat against the walls like the bony wings of a giant albatross.

The wall against which the bed lay was wildly licked by the small river waves and they could hear the lap lap lap against the mildewed flanks.

In the darkness of the barge, with the wood beams groaning, the rain falling in the room through the unrepaired roof, the steps sounded louder and more ominous. The river seemed reckless and angry.

Against the smoke and brume of their caresses, these brusque changes of mood, when the barge ceased to be the cell of a mysterious new life, an enchanted refuge; when it became the site of compressed angers, like a load of dynamite boxes awaiting explosion.

For Rango’s angers and battles with the world turned to poison. The world was to blame for everything. The world was to blame for Zora having been born very poor, of an insane mother, of a father who ran away. The world was to blame for her undernourishment, her ill health, her precocious marriage, her troubles. The doctors were to blame for her not getting well. The public was to blame for not understanding her dances. The house owner should have let them off without paying rent. The grocer had no right to claim his due. They were poor and had a right to mercy.

The noise of the chain tying and untying the rowboat, the fury of the winter Seine, the suicides from the bridge, the old watchman banging his pails together as he leaped over the gangplank and down the stairs, the water seeping too fast into the hold of the barge not pumped, the dampness gathering and painting shoes and clothes with mildew. Holes in the floor, unrepaired, through which the water gleamed like the eyes of the river, and through which the legs of the chairs kept falling like an animal’s leg caught in a trap.

Rango said: “My mother told me once: how can you hope to play the piano, you have the hands of a savage.”

“No,” said Djuna, “your hands are just like you. Three of the fingers are strong and savage, but these last two, the smallest, are sensitive and delicate. Your hand is just like you; the core is tender within a dark and violent nature. When you trust, you are tender and delicate, but when you doubt, you are dangerous and destructive.”

“I always took the side of the rebel. Once I was appointed chief of police in my home town, and sent with a posse to capture a bandit who had been terrorizing the Indian villages. When I got there I made friends with the bandit and we played cards and drank all night.”

“What killed your faith in love, Rango? You were never betrayed.”

“I don’t accept your having loved anyone before you knew me.”

Djuna was silent, thinking that jealousy of the past was unfounded, thinking that the deepest possessions and caresses were stored away in the attics of the heart but had no power to revive and enter the present lighted rooms. They lay wrapped in twilight and dust, and if an old association caused an old sensation to revive it was but for an instant, like an echo, intermittent and transitory. Life carries away, dims, and mutes the most indelible experiences down the River Styx of vanished worlds. The body has its cores and its peripheries and such a mysterious way of maintaining intruders on the outer rim. A million cells protect the coreof a deep love from ghostly invasions, from any recurrences of past loves.

An intense, a vivid present was the best exorcist of the past.

So that whenever Rango began his inquisitorial searchings into her memory, hoping to find an intruder, to battle Paul, Djuna laughed: “But your jealousy is necrophilic! You’re opening tombs!”

“But what a love you have for the dead! I’m sure you visit them every day with flowers.”

“Today I have not been to the cemetery, Rango!”

“When you are here I know you are mine. But when you go up those little stairs, out of the barge, walking in your quick quick way, you enter another world, and you are no longer mine.”

“But you, too, Rango, when you climb those stairs, you enter another world, and you are no longer mine. You belong to Zora then, to your friends, to the café, to politics.”

(Why is he so quick to cry treachery? No two caresses ever resemble each other. Every lover holds a new body until he fills it with his essence, and no two essences are the same, and no flavor is ever repeated…)

“I love your ears, Djuna. They are small and delicate. All my life I dreamed of ears like yours.”

“And looking for ears you found me!”

He laughed with all of himself, his eyes closing like a cat’s, both lids meeting. His laughter made his high cheekbone even fuller, and he looked at times like a very noble lion.

“I want to become someone in the world. We’re living on top of a volcano. You may need my strength. I want to be able to take care of you.”

“Rango, I understand your life. You have a great force in you, but there is something impeding you, blocking you. What is it? This great explosive force in you, it is all wasted. You pretend to be indifferent, nonchalant, reckless, but I feel you care deep down. Sometimes you look like Peter the Great, when he was building a city on a swamp, rescuing the weak, charging in battle. Why do you drown the dynamite in you in wine? Why are you so afraid to create? Why do you put so many obstacles in your own way? You drown your strength, you waste it. You should be constructing…”

She kissed him, seeking and searching to understand him, to kiss the secret Rango so that it would rise to the surface, become visible and accessible.

And then he revealed the secret of his behavior to her in words which made her heart contract: “It’s useless, Djuna. Zora and I are victims of fatality. Everything I’ve tried has failed. I have bad luck. Everyone has harmed me, from my family on, friends, everyone. Everything has become twisted, and useless.”

“But Rango, I don’t believe in fatality. There is an inner pattern of character which you cascover and you can alter. It’s only the romantic who believes we are victims of a destiny. And you always talk against the romantic.”

Rango shook his head vehemently, impatiently. “You can’t tamper with nature. One just is. Nature cannot be controlled. One is born with a certain character and if that is one’s fate, as you say, well, there is nothing to be done. Character cannot be changed.”

He had those instinctive illuminations, flashes of intuition, but they were intermittent, like lightning in a stormy sky, and then in between he would go blind again.

The goodness which at times shone so brilliantly in him was a goodness without insight, too; he was not even aware of the changes from goodness to anger, and could not conjure any understanding against his violent outbursts.

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

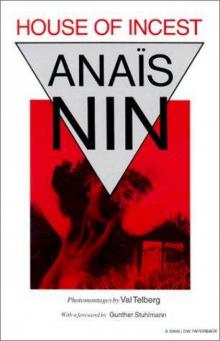

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest