The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Read online

Page 8

Djuna instinctively knew this to be so accurate and inevitable that she would prepare herself for it. On her way back from a trip she would say to herself: “Don’t get exalted at the idea of seeing Rango, for surely Zora will get very ill when you come back and Rango will not be free…”

And then because Rango could not explode or revolt against an illness (which he thought genuine and inevitable), could not see how its developments obeyed Zora’s destructive will, he revolted at other situations, unjustly, inaccurately. Djuna learned to detect the origin of the revolt, to know it was an aborted revolt at home which he diverted and brought to other scenes or circumstances. He exploded wildly over politics, he attacked the illnesses of other womn, he incited other husbands to revolt and would seek them out and take them to the cafe almost by force, just as Djuna indulged now and then in a tirade against helpless or childish women in general because she did not dare to speak openly against Zora’s childishness.

From so many scenes at home Rango escaped to Djuna as a refuge. He would place the whole weight of his head and arms on her knees, and if it happened that Djuna was tired, she did not reveal it for fear of overburdening a man too heavily burdened already. She disguised her own needs, her weaknesses, her handicaps, her own fears or troubles. She concealed them all from him. Thus grew in his mind an image of her infinite energy, infinite power to overcome obstacles. Any flaw in this irritated him like a failed promise. He needed her strength.

Because he seemed to love Zora for her weakness, to be so indulgent toward her inadequacies, her fumbling inability to open a door, incapacity to buy a stamp and mail a letter, to visit a friend alone, Djuna felt a deep unbalance, a deep injustice taking place. For the extreme childishness of Zora robbed her relation to Rango of all its naturalness. It set the two women at opposite poles, not as rivals, but as opposites, destruction against construction, weakness against strength, taking against giving.

To break the hypnosis came certain shocks, which Djuna was losing her power to interpret.

When she had gradually passed to Zora most of her belongings, all of her jewelry—to such an extreme that she had to surrender going to certain places and seeing certain friends where she could not appear dressed as carelessly as she was—she arrived unexpectedly at Zora’s and found her sitting among six opened trunks.

“I’m working on a costume for a new dance,” said Zora. The trunks overflowed with clothes. Not theatre costumes only, but coats, dresses, stockings, underwear, shoes.

Djuna looked bewildered and Zora began to show her all that the trunks contained, explaining: “I bought all this when things were going well for me in New York.”

“But you could wear them now!”

“Yes, I could, but they look too nice. I just like to keep them and look at them now and then.”

And all the time she had been wearing torn shoes, mended stockings, dresses too light for winter, when not wearing all that she had extracted from Djuna.

This discovery stunned Djuna. It proved what she had felt all the time obscurely, that Zora’s dramatization of the poor, the cold, the scantily dressed, the pathetic woman, was a voluntary role which suited her deepest convenience. That this drabness, which constantly aroused Rango’s pity, was deliberate, that, at any moment, she could have been better dressed than Djuna.

That night Djuna could not refrain from asking Rango: “Did you know when I gave up my fur coat for Zora to wear this winter that she had one in her trunk all the time?”

“Yes,” said Rango. “Zora has a lot of the gypsy you could say. Gypsies always keep their finery for certain occasions, and like to look at it now and then, but seldom wear it.”

“Am I going mad?” asked Djuna of herself. “Or is Rango as mad as Zora? He is not aware of the absurdity, the cruelty of this. He thinks it’s natural that I should dispossess myself for a woman obsessed with the desire to arouse pity.”

But as this incident threatened her faith in Rango, she soon closed her eyes again.

The actor does not suffer any cramps because he knows the role he plays he will be able to discard at some stated time, and walk free again to be himself.

But Djuna’s role in life seemed inescapable. She was doomed to be devoted to a cause she did not believe in. Zora would never get well; Rango would never be free. She suffered from pains which were like cramps, because in all these unnatural positions she took, these contortions of giving, of surrender, there was a strain from the knowledge that she could never, as long as she loved Rango, ever be free and herself again.

Out of physical exhaustion she would occasionally run away.

This time to conceal her exhaustion from Rango she took the Dover-Calais boat intending to hide in London for a few days at the house of a friend.

Sitting on deck, on a foggy afternoon, she felt so utterly tired and discouraged that she fell asleep. Tired tired tired, her body sank into deep sleep on the deck chair. Sleep. A deep deep sleep…until she felt a hand on her shoulder as if calling. She would not open her eyes; she would not respond. She dreaded to awaken. She feigned a complete sleep and turned her head away from the hand that was beckoning…

But the voice persisted: “Mademoiselle, mademoiselle…” A voice pleading.

She felt the spray on her face, the swaying of the ship, and began to hear the voices around her.

She opened her eyes.

A man was leaning over her, his hand still on her shoulder. “Mademoiselle, forgive me. I know I should have let you sleep. Forgive me.”

“Why did you wake me? I was so tired, so tired.” She was not fully awake yet, not awake enough to be angry, or even reproachful.

“Forgive me. I can explain, if you will let me. I am not trying to flirt, believe me. I’m a grand blesse de guerre. I can’t tell you how seriously wounded, but it’s left me so I can’t bear fog, damp, rain, or the sea. Pains. Such pains all over the body. I have to make this trip often, for my work. It’s torture, you know. Going back to England now… When the pains start there is nothing I can do but to talk to someone. I had to talk to someone. I looked all around me. I looked into every face. I saw you asleep. I know it was inconsiderate, but I felt: that’s the woman I can talk to. It will help me—do you mind?”

“I don’t mind,” said Djuna.

And they talked, all the way, on the train too, all the way to London. When she reached London she was near collapse. She took the first hotel room she could find and slept for twelve hours. Then she returned to Paris.

No more questioning, no more interpretations, no more examinations of her life. She was resigned to her destiny. It was her destiny. The grand blesse de guerre on the ship had made her feel it, had convinced her.

So she made a pirouette charged with sadness, on the revolving stages of awareness, and returned to this role she had been fashioned for, even down to the face, even when asleep.

But when people play a role motivated by false impulses, moved by compulsions formed by fear, by distortions, rather than by a deep need, the only symptom which reveals that it is a role and that acts do not correspond to the true nature, is the sense of unbearable tension.

The ways to measure one’s insincerities are few, but Djuna knew that the most infallible one was joylessness. Any task accomplished without joy was a falsity to one’s true nature. When Djuna indulged in an extravagant giving to Zora she felt no joy because it was misinterpreted by both Rango and Zora. If there was a natural goodness in Djuna it was not this magnified, this self-destructive annihilation of all of herself.

But this role could last a lifetime, since Rango denied the possibility of change by clairvoyance, the possibility of a lucid change of direction. They were rudderless and at the mercy of Zora’s madness.

She did not even gain the prestige granted to the professional actor, for there is this about roles played in life, and that is that no one is deceived. The most obtuse, the most insensitive people feel a dissonance, sense an imposture, and, whereas the actor is resp

ected for creating an illusion on the stage, no one is respected for seeking to create an illusion in life.

She planned another escape, this time with Rango and Zora. She felt that taking them to the sea, into nature, might heal them all, might strengthen Zora and bring them peace.

It was a most arduous undertaking to get Zora to pack and to free Rango from all his tangles. They missed not one but several trains. Zora had two trunks of belongings. Rango had debts and his debtors were reluctant to let him leave Paris. They overslept in the mornings.

Rango borrowed some money and bought Djuna a present, a slender white leather belt from Morocco. It was his first present and Djuna was overjoyed and wore it proudly. But when the three met at the station she found Zora wearing an identical belt, so her own lost its charm for her and she threw it away.

The fishing port they reached in the morning lay in the sun. The crescent-shaped harbor sheltered yachts and fishing boats from all over the world. The cafes were all gathered on the edge and as they sat having coffee they saw the boats come to life, the sailors and voyagers emerging from theircabins. They saw the small portholes open, the hatches lifted, and sails spread. They saw the sailors starting to polish brass and wash decks.

Behind them rose the hills planted with white houses built during the Moors’ invasion of the Mediterranean coast.

The place was animated, like a perpetual carnival. The fluttering, glitter, and mobility of the harbor and ships were reflected in the cafes and visitors. Women’s scarves answered the coquetries of the sails. The eyes, skins, and smiles were as polished as the brass. Women’s sea-shell necklaces reflected the sky and the sea.

Rango found a place for Zora and himself at the top of a hill within a forest. Djuna took a room in a hotel farther down the hill and nearer to the harbor.

When Rango came down the hill on his bicycle and met Djuna at one of the cafes on the port, the sun was setting.

The night and the sea were velvety and caressing, unfolding a core of softness. As the plants exhaled a more mysterious flowering, people, too, shed their brighter day selves and donned colors and perfumes more appropriate to secret blooms. They dilated with the leaves, the shadows, at the approach of night.

The automobiles which passed carried all the flags of pleasure unfurled in audacious smiles, insolent scarves.

All the voices were pitched to a tone of intimacy. Sea, earth, and bodies seeking alliances, wearing their plumage of adventure, coral and turquoise, indigo and orange. Human corollas opening in the night, inviting pursuit, seeking capture, in all the dilations which allow the sap to rise and flow.

Then Rango said: “I must leave. Zora is afraid of the dark.”

To make it easier for Rango she bicycled back with him but when she returned alone to her room all the exhalations of the sea tempted her out again, and she returned to the port and sat at the same table where she had sat with Rango and watched the gaiety of the port as she had watched that first party out of her window as a girl, feeling again that all pleasure was unattainable for her.

People were dancing in the square to an accordion played by the village postmaster. The letter carrier invited her to dance, but all the time she felt Rango’s jealous and reproachful eyes on her. Every porthole, every light, seemed to be watching her dance with reproach.

So at ten o’clock she left the port and its festivities and bicycled back to her small hotel room.

As she climbed the last turn in the hill, pushing her bicycle before her, she saw a flashlight darting over her window which gave on the ground floor. She could not see who was wielding it, but she felt it was Rango and she called out to him joyously, thinking that perhaps Zora had fallen asleep and he was free and had come to be with her.

But Rango responded angrily to her greeting: “Where have you been?”

h, Rango, you’re too unjust. I couldn’t stay in my room at eight o’clock. It’s only ten now, and I’m back early, and alone. How can you be angry?”

But he was.

“You’re too unjust,” she said, and passing by him, almost running, she went into her room and locked the door.

The few times that she had held out against him, such as the time he had arrived at midnight instead of for dinner as he had promised, she had noticed that Rango’s anger abated, and that his knock on the door had not been imperious, but gentle and timid.

That is what happened now. And his timidity disarmed her anger.

She opened the door. And Rango stayed with her and they sought closeness again, as if to resolder all that his violence broke.

“You’re like Heathcliff, Rango, and one day everything will break.”

He had an incurable jealousy of her friends, because to him friends were the accomplices in the life she led outside of his precincts. They were the possible rivals, the witnesses, and perhaps the instigators to unfaithfulness. They were the ones secretly conniving to separate them.

But graver still was his jealousy of the friends who reflected an aspect of Djuna not included in her relationship to Rango, or which revealed aspects of Djuna not encompassed in the love, an unknown Djuna which she could not give to Rango. And this was a playful, a light, a peace-loving Djuna, the one who delighted in harmony, not in violence, the one who found outside of passion luminous moods and regions unknown to Rango. Or still the Djuna who believed understanding could be reached by effort, by an examination of one’s behavior, and that destiny could be reshaped, one’s twisted course redirected with lucidity.

She attracted those who knew how to escape the realm of sorrow by fantasy. Other extensions of Paul appeared, and one in particular of whom Rango was as jealous as if he had been a reincarnation of Paul. Though he knew it was an innocent friendship, still he stormed around it. He knew the boy could give Djuna a climate which his violence and intensity destroyed.

It was her old quest for a paradise again, a region outside of sorrow.

Lying on the sand with Paul the second (while Rango and Zora slept through half of the day) they built nine-pins out of driftwood, they dug labyrinths into the sand, they swam underwater looking for sea plants, and drugged themselves with tales.

Their only expression of a bond was his reaching for her little finger with his, as Paul had once done, and this was like an echo of her relation to Paul, a fragile bond, a bond like a game, but life-giving through its very airiness and delicacy.

Iridescent, ephemeral hours of relief from darkness.

When Rango came, blurred, soiled by his stagnant life with Zora, from quarrels, she felt stronger to meet this undertow of bitterness.

She wore a dress of brilliant colors, indigo and saffron; she brushed her hair until it glistened, and proclaimed in all her gestures a joyousness which she hoped would infect Rango.

But as often happened, this very joyousness alarmed him; he suspected the cause of it, and he set about to reclaim her from a region she had not traversed with him, the region of peace, faith, and gentleness he could never give her.

True that Paul the second had only appropriated her little finger and laid no other claim on her, true that Rango’s weight upon her body was like the earth, stronger and warmer, true that when his arms fell at her side with discouragement they were so heavy that she could not have lifted them, true that those made only of earth and fire were never illuminated, never lifted or borne above it, never free of it, but hopelessly entangled in its veins.

Her dream of freeing Rango disintegrated day by day. When she gave them the sun and the sea, they slept. Zora had ripped her bathing suit and was sewing it again. She would sew it for years.

It was clear to Djuna now that the four-chambered heart was no act of betrayal, but that there were regions necessary to life to which Rango had no access. It was not that Djuna wanted to house the image of Paul in one chamber and Rango in another, nor that to love Rango she must destroy the chamber inhabited by Paul—it was that in Djuna there was a hunger for a haven which Rango was utterly incapable of giving to

her, or attaining with her.

If she sought in Paul’s brother a moment of relief, a moment of forgetfulness, she also sought in the dark, at night, someone without flaw, who would protect her and forgive all things.

Whoever was without flaw, whoever understood, whoever contained an inexhaustible flow of love was god the father whom she had lost in her childhood.

Alone at night, after the torments of her life with Rango, after her revolts against this torment which she had vainly tried to master with understanding of Rango, defeated by Rango’s own love of this inferno, because he said it was real, it was life, it was heightened life, and that happiness was a mediocre ideal, held in contempt by the poets, the romantics, the artists—alone at night when she acknowledged to herself that Rango was doomed and would never be whole again, that he was corrupted in his love of pain, in his belief that war and troubles heightened the flavor of life, that scenes were necessary to the climax of desire, like fire, suddenly in touching the bottom of the abysmal loneliness in which both relationships left her, she felt the presence of god again, as she had felt him as a child, or still at another time when she had been close to death.

She felt this god again, whoever he was, taking her tenderly, holding her, putting her to sleep. She felt protected, her nerves unknotted, she felt peace. She fell asleep, all her anxieties dissolved. How she needed him, whoever he was, how she needed sleep, she needed peace, she needed god the father.

In the orange light of the fishing port, the indigo spread of the sea, the high flavor of the morning rolls, the joyousness of early mornings on the wharf, the scenes with Rango became more and more like hallucinations.

Rango walking through the reeds seemed like a Balinese, with his dark skin and blazing eyes.

When they sat at the beach late at night around a fire and roasted meat, he seemed so in harmony with nature, crouching on his strong legs, nimble with his hands. When they returned from long bicycle rides, after hours of pedaling against a brisk wind, tired and thirsty but drugged with physical euphoria and content, then the returns to his obsessions seemed more like a sickness.

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

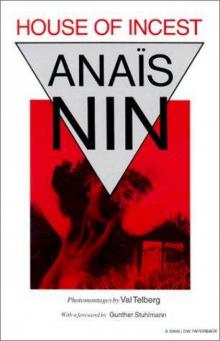

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest