Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 Read online

Page 5

Letter to Henry:

Yes, I saw Varda, at parties. Loved him. See him as you do, a free, lusty and joyous man, a poet but a real man, very youthful, and his love of women is a relief after so much disparaging I see around me. He turns them into myths, poems, collages, delights of all kinds.

Letter from Leonard W.:

Dear Miss Nin: This letter is mostly an expression of reverence mixed with a little awe, and quite a bit of appreciation. I first saw your name in a dedication of Henry Miller's and it was Wallace Fowlie who urged me to read your stories and lent me Under a Glass Bell. ...I honestly found everyone of the stories very good, especially "Je Suis le Plus Malade des Surréalistes" and "Birth." One of the things which struck me most was the poetic quality of every phrase, each if changed in any way would be ruined, it seems, and the beautiful images evoked, as in the labyrinth. I was a bit worried when I read in the preface that you considered destroying them. It make one think: What had she written before that might actually have been destroyed and what will the succeeding book be like? I haven't yet been able to find Winter of Artifice, so I have only to hope that the change is for the best, as of course, it probably is. If you have any copies left of any or all your books and if you are willing to part with them, I will feel really honored if you will allow me to buy some from you. For even if I have read a particularly good book many times, nothing gives me greater pleasure than to own a copy. I also wish I had a book printed so that I would be able to offer you a copy in gratitude. It is really too soon for me to start analyzing why I like your stories so much, or what it is in them that attracts me so, but one thing I know is this. After the emotional storm of Une Saison en Enfer, and Les Chants du Maldoror, it is pleasant and somewhat of a relief to sail more leisurely in the quieter waters of Under a Glass Bell, although I must confess, often my anchor finds no bottom even there. Upon re-reading I find that the above is not a particularly felicitous metaphor, but it serves. Another thing I admire very much and would like to cultivate in my own work is the unity of each story. Each is as structurally perfect as the Ferris wheel in "The Mohican," and yet the pulse of life is felt along the entire periphery. Well, I have said enough. I hope I have managed to convey some part of the deep admiration and appreciation I feel for your work.

I answered and mailed him a copy of Winter of Artifice.

Letter from Leonard W.:

I received your wonderful letter and this afternoon the book. I am now on the fifteenth reading of the letter, and each time I get the same feeling of elation that I did at first. As for Winter of Artifice, I can only echo the words of Rebecca West, Edmund Wilson and Henry Miller. However, here is how it struck me. The whole music metaphor in Winter of Artifice was a superb thing in itself. I liked very much all of "The Voice." The orchestra symbols are very interesting. I have been hearing many provocative things lately about your diary. I hope sincerely you can either publish it yourself or find someone who will. I promise you I shall send you the money for the book I received as soon as I pay a slight debt to Henry Miller for a painting. I showed Mr. Fowlie what you said about his article in the Kenyon Review and he was indeed pleased. We will both see you soon, I hope. As regard to my work, which you show such a kind interest in, I am working on a short story now. You see, everything I had written before I took Mr. Fowlie's course in contemporary French authors had been so much in the romantic schoolboy vein that I have rejected it all. As a matter of fact, I can say without exaggeration that an entirely new world was revealed to me when I swallowed my first mouthful of Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Miller, André Gide, Verlaine, Proust and boundless others....So I am just beginning to write. And from all present indications it will be months and years before the influence of this new order of literature has assumed its proper proportion in my life. But I talk too long of me. I am quite overwhelmed when I read a letter like yours regarding cooperation between the artist and the public. Relatively unknown and unsung men like Miller, George Leite in California, yourself, who raise money for destitute authors, encourage one another, overwhelm me with humility. I think I would rather be one of your numbers than a Somerset Maugham or a Booth Tarkington. Sometimes I feel like consecrating myself to the task of becoming a millionaire, so that I might provide grants or funds for a publishing company, the kind that would publish the volumes of Anai's Nin's journals in vellum and gold ink. Well, I have taken enough of your time I am afraid. Thank you again for the book and the letters and even more for your warm interest. I cannot close without re-iterating my admiration for your technique which I can't quite define yet and for the beautiful and fearless flow of symbols, the one merging into the other in perfect metamorphosis, like the themes of Stravinsky's "Petrouchka."

A snowstorm. I was working on This Hunger, when my typewriter broke down. I went out into the snow with it to get it repaired. When I came back, I did not feel like writing the continuation of Djuna's life at the orphan asylum and her hunger. I felt like writing about snow. I wrote every image, every sensation, every fantasy I had experienced during my walk. The snowstorm had thrown me back into the past, into my innocent adolescence, surrounded by desires, at sixteen, intimidated, tense. I compared my adolescence with the frozen adolescence of others around me today. They all fused: snow, the frost of fear, the ice of virginity, purity, innocence, and always the sudden danger of melting. I wrote myself out. And when I was finished, I realized I had described Djuna's adolescence, and the adolescent contractions of other adolescents. I had written thirty-eight pages on the snow in women and men, on Djuna and the asylum, her hunger.

Town and Country magazine had published a photograph of me dressed fashionably by Henry La Pensée. The photographer heard me describe the four women of my next book and wanted to experiment with a photograph in which I would dress differently for each character, and then as myself, Anai's, the novelist, in the center. I assembled the clothes which seemed to fit Lillian, Djuna, Stella, Hejda. For Lillian I chose the evening suit altered to fit me (when we all wanted to imitate the woman captain, Valentina), with a more severe shirtwaist. I dressed my hair severely, and what did I see in the mirror? A resemblance to my father, who wore his hair long in the back, as artists of his time did. This amused me, and appealed to my love of disguises. Then I dressed as Hejda, oriental, with a veil across the face. Stella, of course, was soft and feminine, pliant; and the novelist in the center was dressed simply, and looked up naturally between her "characters." All this was done in a playful, surrealist mood. The photographer made a collage. But Town and Country was not amused. Nothing came of it. The photographer gave me the photograph.

Days of feverish inspiration, a flood of spontaneous writing. Onrush of associations, of impromptu anecdotes, utter freedom. What has happened is that I have touched off such a deep level of unconscious life that the women lose their separate and distinct traits and flow into one another. As if I were writing about the night life of woman and it became all one. The boundaries, distinctions, are erased; on that subconscious level, people are the same: emotions, instincts, dreams. As I lose my grip on construction, on realism, I seem to gain another kind of reality. I emerged today with thirty-eight pages on the snow woman, adolescence, the virgin woman, interwoven with the story told to me by Frances of her life in the orphan asylum.

The beauty of this moment is in my freedom. My abundance of love able to live itself out, to keep everyone in a state of romance, to make each hour, each evening, each moment yield up its fullness. To disperse and dispense tenderness, attentiveness, joy in living.

Twenty years ago Elsa De Brun lived in Forest Hills, where I took the train to go to work. She saw me walking toward the station and she said to herself: "If ever I am in trouble, this is the woman I will go to." And twenty years later she was in trouble and sought me out. She had bought a bad sketch of me made by a Village artist. She had collected all my books and photographs. Her first question, even before she talked about herself, was how did I feel about woman. I answered: "I feel great warm

th and lively friendship, but never sexual desire. I once had a desire for June, which was never lived out."

Our life is composed greatly from dreams, from the unconscious, and they must be brought into connection with action. They must be woven together. It is not because I love complexity that I have tried to gather together all the elements. Frances called it symphonic, a vast gathering together. This is the way we live. She did speak against ornamentation. When will I write a quartet? But the unconscious does produce these great intricacies, multiple levels and facets. I listen to music as never before, bathe in it. My symphonic writing puzzles those I love and trust. But I have had only the desire that writing should become music and penetrate the senses directly. For this, poetry is necessary. The unconscious speaks only the language of symbol. That is my language.

Frances responds to the direct statement I make about woman in the preface. But that is the writing of the intelligence. It is not the writing of emotion and the senses, which I seek. I want meaning to enter the body by some other route, not the mind. I am not writing with the mind. Frances likes it when my mind appears to explain. I like it best when I am submerged in symphony, and when the world in my head becomes a world of images and music. Writing has for too long been without magical power. In me everything was married, love and the body, heaven and hell, dream and action. No analytical dismemberment or separation of elements. As a woman, I shall put together all that was divided and give new birth to everything that was killed.

Edmund Wilson invited me for lunch. I felt his distress, received his confession. Even though not an intimate friend, Wilson senses my sympathy and turns toward it. He is lonely and lost. He is going to France as a war correspondent. He asks me to accompany him while he buys his uniform, his sleeping bag. We talk. He tells me about his suffering with Mary McCarthy.

I rewrote the snow passage and then that of the yielding of woman.

The book is taking shape. The women have been divided into elements: Djuna, perception; Stella, blind suffering; Sabina, the free woman; Lillian, the one who seeks liberation in aggression.

The nearness of the Russians to Berlin—ninety miles—is the feverish theme of all our talks and interest. A terrifying moment for the world.

[March, 1945]

I feel the spring. I enjoy Pablo's gaiety, Charles Duits' poetry. I am writing, loving, and choose to believe the letters I receive rather than the sour reviewers.

The bell rang unexpectedly. At the door stands a most beautiful man of seventeen, tall, slender, blond, with deep-blue eyes, long lashes, a transparent skin like a jeune fille en fleur, a great seriousness in his bearing, a shyness, an innocence, a purity. It all radiates from him as he stands there and says: "I am Leonard W."

He was born in Manila of American parents, spent four years in Manila, four years in China, then America. But the early uprootings created loneliness. He has incredibly slender hands. His eyes are long, slanted, almost oriental when he is dreaming, but intense and hypnotic when he examines you. The curiously blue shadows over them when he looks down, blue shadows of a celestial blue. He destroyed his diary, his adolescence, when he came home from college. He brings me a story he wrote, his water colors, and leaves them with me to be blessed, he said. I am rich indeed with young men's dreams and worship. They create a world so distinct from the harsh, purely intellectual, unemotional and unimaginative world of people like Edmund Wilson, editors of Partisan Review, etc.

I had spoken of Leonard's hypnotic eyes. So many blue eyes look diluted, as if painted by a water colorist, but his are intense, like the deepest part of the ocean in some prestorm mood. And last night when he came, he told us that he could hypnotize people. Pablo offered himself for the experiment. He lay on the couch and Leonard, in a deep, rich, tranquil voice, talked to him monotonously until he fell asleep. Leonard told Pablo: "You are now two years old." Pablo said in Spanish: "Agua."

Leonard: "Now you are three years old."

Pablo said: "Nanny."

Leonard: "Now you are four years old."

Pablo sat up and sang a little song in an unknown language. At age five he said: "I broke a vase," and went to stand at the corner of the room, face to the wall, for punishment. At seven he asked for paper and pencil and drew the face of a little girl with a boarded-up mouth. Leonard offered him a cigarette which he smoked awkwardly, making a wry face and coughing.

"You are now at home, in Panama. What do you want to do?"

Pablo: "Lie on the sand, in the sun, or swim."

"Now you are in New York. What do you want to do?"

"Write and paint," said Pablo.

Leonard asked him to sing a song like Sablon. Pablo did. Then to sing the same song in an operatic way. Pablo did. And he did this with open eyes but a fixed, empty glance, and a childlike expression of complete submission. He was told to act drunk. He stumbled about. Then Leonard gave his final order: "When you awaken, you will not see Anais. You will not see Anai's until I snap my fingers."

Pablo awakened. Leonard had given me a letter to hand to him. Pablo saw the letter but not me. Then he tried to sit on the chair where I was sitting. When I touched his hair, he brushed my hand away as if it were an invisible insect. We were all half-anxious, half-amused, half-fearful of Leonard's power. Leonard was smiling, firm and dominant. The beauty of his face was astonishing, its paleness, the fine, clear, lean lines of the cheekbone, the very full sensuous mouth, the boy's hair, tousled, falling over his eyes, the very image of what mystics or poets should look like.

Another evening of hypnotism. This time for Luise Rainer and Frances. Leonard hypnotized Pablo. Told him that he was Roosevelt and must make a speech. Pablo was sitting on the couch. He did not move. We thought the hypnosis had failed. But when Leonard repeated his order, Pablo said: "I need help to rise." Roosevelt. A chill ran down our spines. Then with help he did get up, and he made a very Roosevelt-like speech. Then Leonard told him he would not see Luise Rainer when he awakened. And Pablo did not see her. When it was time to leave, Leonard had still not snapped his finger, saying: "Now you can see Luise." Pablo was standing by the door on his way out. Luise had gone into the kitchen for a glass of water. The kitchen light was behind her. Her shadow appeared on the white wall by the entrance. Pablo saw this shadow, but not her, and was disturbed. The next day he said he would not submit to hypnosis again, that it frightened him, this loss of his will, and being controlled by Leonard to such an extent. He was afraid it would affect his will, or influence him into acts he did not wish to enter into.

Letter from Henry:

George Leite showed me your wonderful letter about Circle magazine and other things, since it contained a message for me. At the same time I had a letter from Wallace Fowlie saying he had plucked up enough courage to visit you (more courage than I had). No, I knew you had not left for Europe yet. I hear about you all the time, from this one, and that. I would have seen you in New York but I had a feeling you did not want to see me. Now that the ice is broken perhaps we can write one another again. For the moment I don't know what to say. Just glad to know you're alive and in good spirits. I am surprised about your change of plans. Somehow I expect still more changes. Did you know that Maurice Kahane is still carrying on in Paris? He changed his name during the war to Girodias. I get letters from soldiers in Paris telling me all our books are prominently displayed in the shops and selling well, yours, [Michael] Fraenkel's, Durrell's and mine. Will we ever get royalties from them I wonder. I'm eager to see your new work. George Leite is going to show me whatever you send. Durrell always asks about you. Do write when you can. I miss you.

Wallace Fowlie, at Yale, read Under a Glass Bell. This started a correspondence between us. I loved the way Fowlie wrote about the poets, like a poet and not an academician. His interpretations were inspiring.

When Fowlie came to see me I found a quiet, small man, dressed in a dark suit, with soft hands. Somehow, he seemed muted, self-effacing, impersonal. His love of Henry Miller's writing did not

seem compatible with the first impression I had.

We talked about literature, mostly. Fowlie speaks perfect French. In fact that Anglo-Saxon, prudish appearance and the perfect knowledge of French and French literature seemed like one more paradox. I liked him and believed we would have a good friendship.

Leonard and I sat in Washington Square talking over his rebellion against his family. They sound abnormally rigid. I took him to the press. He wanted to help. He looks exhausted after the sessions of hypnosis, as if he had made love.

"Can you make someone fall in love with you?"

"That would be a poor kind of love."

Later Leonard said: "If I had a place to stay, I would leave home."

Tom and Frances Brown offered him a small room next to their apartment, with a separate door. I offered him food and pocket money. He has only two months of freedom before he goes into the army, and would like to live as he feels for this precious period.

"I feel I know what I want now, not only from reading books and knowing you, but from sharing your life, the spontaneity of Pablo, the vitality of Josephine, the gay creative atmosphere, the other friends, and the warmth."

"Do you feel emotionally ready to cut yourself off from your family?"

"They are not my real spiritual family. You are."

Sunday afternoon we went to Pelham Bay, to look for a houseboat for Pablo. I dressed in Pablo's sailor suit and beret. Saturday evening we had a party, a warm, lively, joyous evening, with Josephine singing and drumming and making us all sing and drum and dance. Luise Rainer came; Frances; Tony Smith, a mystical architect, and his actress-wife, Lawrence. Others brought friends. At the end of the evening Leonard hypnotized Marshall, another beautiful young man, who had come with a harp player. When Marshall returns to age one, two, three, etc., we find it comical. But we are afraid to let Leonard try: "And before that, further back." Suppose Marshall remained a baby, did not return? He has huge green eyes, a golden tan skin, soft features. And all of them are full of invention. Leonard and Pablo fought a duel with two metal measuring tapes. The tapes would at times remain stiff like swords, and then unexpectedly and absurdly collapse just at the moment of victory.

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

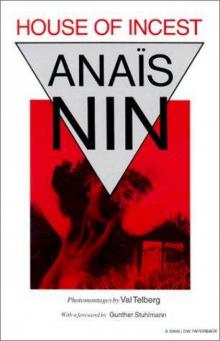

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest