Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 Read online

Page 6

Leonard sculpted a metal bird of paradise and we hung it from a thread in the middle of the room. At the slightest wave of air it spins, seems to be flying. He also painted scenes with fluorescent paints which only show in the dark, so at night the studio appears to be an exotic jungle. Pablo brought a hamster whose hair he had dyed blue.

After the party Leonard talked about his dramas at home.

He wanted to know why we were all willing to help him.

"I think it's an act of faith in you," I said. "We all believe in you. You belong with us."

"When I grow up, I will be able to do the same for others."

"Yes, of course." His saying: "When I grow up" made me aware of his youth. When he leaves, he places his delicate, sensitive, soft-skinned hands in mine as if he would leave them there, in a shelter.

Sunday was the critical day for him. His father wanted him to go to work with him downtown on Monday morning. His father owns an oil company. Leonard said he first had to go to Yale to collect his belongings.

Monday morning he appeared at my door with his valise.

"Your real life is beginning."

"I feel I have gained more than I have lost."

We went together to Frances' apartment on Charles Street. We tidied the guest room. And then the dream began. Leonard eating with us, sharing all our evenings, sharing books, music, my friends, playing chess with Tom, smiling at times like a child, at others like an old soul, talking about transmigration, making sketches of me, eager to harmonize with all our activities. (His family found him cold, stubborn.)

I began to see him as Jakob Wassermann's Caspar Hauser, because of his innocence and sudden insights. He has intuitions about people which are those of an old soul. There is no trace of his upper-class, sheltered, narrow life. He is an adventurer in spirit, has spiritual courage. He reads everything, absorbs, evaluates. His body alone is bound.

He dreamed that his father and mother came to take him back and that he rebelled.

At times he is inarticulate, confused. Or at other times withdrawn and separate.

Leonard pastes a small piece of mirror between my eyes: "Your third eye." He pastes silver paper over my toe nails. When I tell Frances how I see Leonard, she says with her usual wisdom: "The future Leonard."

[April, 1945

Fascinating to watch in Leonard the oscillations between adolescence and manhood. He wears a white scarf and walks through shabby streets as if he did not see them. He got drunk for the first time at Frances'. He wanted me to open the diary and show him what I had written about him.

"The diary would be destroyed if I opened it. To be able to tell the truth I have to maintain the mystery."

"I will hypnotize you, make you open the safe, and read them all."

In three weeks he has to go to war. His mother seeks an interview. She talks badly about decadent artists, and he passes judgment on her. His father calls him to discuss his "future."

Pablo and Leonard painted a tapestry which hangs over my bed. They decorate bottles, make collages and drawings. I come back from the hard work at the press, from pressing debts, talk of Helba's illness, and I find them all at work. I make tea and honeybutter.

Leonard's father had come to Tom's and Frances' apartment to see the kind of place his son was living in. He set a detective to watch my life. He took my books to a lawyer, and the lawyer admitted there was nothing in either book to incite a young man to break with his parents. He said at worst they were "bizarre," but nothing the law could attack. And the other book, Lautréamont's Maldoror, well he was a writer who had been dead for a hundred years and could not be sued. He tried to harm Wallace Fowlie and complained to the college about the books Fowlie had given Leonard to read. Power against spirit. Frances' husband, Tom, the coolest one, was delegated to talk to Leonard's father. He gained his confidence. Lightning was averted for a time.

When Leonard is happy he hugs me so tightly that I said: "You're flattening me into a wafer."

"The better to commune with, my dear."

He opens and reads all my letters.

Lanny Baldwin is another who, while enjoying the writing, enjoying the character of Lillian, tells me over the telephone, referring to all that'is missing around Lillian: "We will get down to brass tacks." When he came, we did not get down to brass tacks. He climbed to my stratosphere.

Frances gives me a small velvet hat with a trailing feather, the latest fashion. Pablo repainted the feather a more vivid pink. I wear this dashing hat when we go to the theater or ballet.

After Leonard's father visited Frances' and Tom's apartment to see the kind of people his son was staying with, we expected him also to come to my studio. I climbed a ladder and took down the colored bird of paradise. But he did not come.

He sent a detective instead to question me.

The detective found the studio occupied by Pablo and Leonard, both painting on the same canvas a luxuriant jungle with exotic birds and flowers k la Rousseau. Pablo's hamster was chewing lettuce in his cage. Fresh engravings lay drying between blotters. I was typing my new book. His comment: "Not much to report."

We went to the ballet and sat up in the balcony, far too much to one side, while downstairs Leonard's father's box yawned empty.

Joaquin's "Quintet for Piano and Strings" was played at the Museum of Modern Art.

In my brother's music there is always a sense of space, air, as if the lyrical experience had been distilled into a light essence and become transparent. The color gold is always a part of it. Emotion is contained, but always clear and strong.

Joaquin's piano recitals and his compositions are a permanent motif in my life, confirming my convictions that music is the highest of the arts.

When he was five years old, a spirited and restless child no one could tame, he would spend hours absolutely still on the staircase of our home in Brussels, listening to the musicians rehearsing. That was the sign of his vocation. We both listened. I can still hear the lines of Bach which were most often repeated. Joaquin became a musician, and in me music was channeled into writing.

In New York, in the brownstone on Seventy-fifth Street, he studied piano with an eccentric old maid, Emilia Quintero, whom I often described in my childhood diary. She kept a white silk scarf of Sarasate's as others keep a memento of a saint. She had loved him secretly and hopelessly. Some of this love was transferred to the handsome Joaquin.

His music was always there. In Richmond Hill he practiced every hour he did not spend in school. In Paris he practiced all day, in spite of delicate health. In Louveciennes he had his studio in a large, beautiful attic room. There was not only the practicing, but even in childhood there were moments of improvisation, the forerunners of his later compositions.

In Paris we had adjoining apartments. He was studying piano with Paul Braud at the Schola Cantorum, and privately with Alfred Cortot and Ricardo Vinez. He studied harmony, counterpoint, and fugue with Jean and Noel Gallon of the Paris Conservatory. He studied musical composition with Paul Dukas at the Paris Conservatory, and privately with Manuel de Falla in Granada, Spain.

I heard him study and compose by the hour. In Louveciennes, when he grew weary of the discipline, he would visit my mother in her apartment, and then me at my typewriter, and ask "Tum'aime?"

Satisfied and recharged, he would go back to work. He drew his strength from his love, never from hatred, and later it was his capacity for love, understanding, and forgiveness which kept the family from estrangements. He was always trying to reunite and reconstruct the family unit. He never took sides, judged, or turned a hostile back on anyone.

He gave concerts in Spain, France, Switzerland, Italy, Belgium, Denmark, England, the United States, Canada, and Cuba.

He is proud and modest, unassuming and yet uncompromising, unable to cripple a rival, push anyone aside, or assert himself.

When he whistles, it means he is standing by his piano writing down his compositions, correcting his scores.

Once, in

Paris, he destroyed one movement of a quintet whose motif I loved. He commented it was too romantic. Perhaps I heard in it the wistful adolescent parting from adolescent sorrows. Perhaps he had, musically, very good reasons for casting it off, to reach a more austere modernism. But I felt the loss as emotional, and its disappearance as a part of Joaquin himself that he was shedding for more rigorous standards. It coincided with the burning of his diaries. Ten years later, during a period of psychoanalysis, I came out singing the entire melodic theme, I who am not a musician and who cannot read music. This proved to me how deeply his music penetrated an unconscious universe. Even when apparently forgotten, lost, this fragment had remained imbedded in me.

In my father there was a distinct faithfulness to Spanish folklore. Spain was recognizable in the themes he embroidered on and harmonized for concert use. With Joaquin something else happened, which brought his music into the realm of modern universal compositions. The Spanish themes became transformed into something more abstract, more unconscious, not the cliché Spain. He modernized the colors, the fervors, the richness of Spain into daring abstractions. It was a far more complex and subtle Spain. There was a tension between simplicity, the single line, and the highly evolved complexities of colors and tones. The intricacies, like the Moorish lacework of Granada, were always unified into the single wistful chant of "cante Jondo."

I spoke of the color gold. There is always a crystalline quality, the transparencies of truth, a strange faculty for musical sincerity which never reaches a common, explicit statement. The composition always spirals away deftly from a familiar statement. It appeals to a third ear, an unborn ear, the ears of today, more intricate but always true: he has a perfect pitch of the soul.

He explores constantly for daring juxtapositions, daring multiplicities, and superimpositions. He achieves radiations, luminosities, and sparkle. The human being and the composer are one. The sources are good humor, generosity, hidden sorrows he does not burden others with, gray days and joyous days, back-breaking labor and early morning whistling.

Joaquin never slides into anger, caricature, or emptiness, or into any of the artifices and pretensions of some of his contemporaries.

I am sure that listening to his music directed my choice of words, my search for rhythm, my ear for tonalities, my use of the unconscious as a many-voiced symphony. I am sure he is the orchestra conductor who quietly and modestly indicates the major theme of the diary; words similar to music which can penetrate the feelings and bypass the mind. His music, far from being in the background of my life, was in the foreground. It was he as a musician who accomplished what I dreamed of, and I followed as well as I could with the inferior power of words. The ear is purer than the eye, which reads only relative meaning into words. Whereas the distillation of experience into pure sound, a state of music, is timeless and absolute.

As a human being, he is the strongest influence in my life, for it is not the failed relationships which influence our life—they influence our death. With Joaquin I had the model of the best relationship I had throughout childhood and adolescence. True, I had to take care of him; he was five years younger. True, it was he who lived out the wildness, the freedom, the independence, while I had to become responsible for his safety, his well-being. But in return he gave the greatest responsiveness and tenderness. He was loving and loyal. We never quarreled. Once, when I lost some money given to me for marketing (when we had little enough), he offered to take the blame. He was ten years old. He set the pattern for the many little brothers I was to have, whose life I must watch over but who return an immense care and tenderness. He never passed judgment, he was never critical. Our lives were different, but we kept an immense respect for each other.

Just as Joaquin's discarded composition had sunk into my unconscious and disappeared for ten years, to be remembered then clearly and completely, I was startled to find that a book read ten years ago in France, Leon Pierre Quint on Proust, had so deeply influenced my attitude toward writing that today what I have written about the craft seems taken from it. Of all the books written about Proust, none have come to the level and beauty of this one. It is the only book Proust might have read without pain. There is not one false note in it. Quint was a writer on the same level as Proust, could comment on and describe him like a twin, as if Proust himself had stood away from his work arid clarified it. He is as refined, as subtle, as accurate, and as penetrating in writing of Proust's life and work as Proust was in his analysis of people. Usually the critic is a lesser writer and a lesser psychological interpreter. He diminishes the work in order to allow himself and others like him to enter the world of the novelist.

Leon Pierre Quint was never translated. He should have been.

Here are some of my favorite excerpts:

Proust's philosophy of instability, mobility, flow and continuity...

Our unconscious is the supreme reality of our inner life.

All the personages of Proust are painted in large incomplete frescoes, like the statues of Rodin which leave room for mystery. The fragments that are missing correspond to the evolution of the character and those that are carefully wrought are powerful enough to suggest his life in the past and in the present.

How is it that the critics did not understand that each time a writer discovers a new subject for study, bourgeois morality is alarmed, that each time the writer enters an unexplored domain he appears sacrilegious. Yet the very existence of art depends on its exploration of the parts of life which have not yet been opened, even on its creation of new modes of life.

A particular trait of his vision of people, which was to become more intensely developed with time, was telescopic. It brought people very close to him, limiting the width of his field, but giving him perception into all their complexities.

And these:

He knew that when our wishes were fulfilled it is never at the time or in the circumstances which would have given the greatest pleasure. It should have happened as soon as the wish was made. When he heard one of his friends say: "I would love to have this or that" he would get it for him immediately, not at Christmas or New Year. He remembered that a pleasure too long awaited is a lost pleasure.

His novel, as he said himself, is real because nothing is more real than the contents of the self; but it is not realistic.

If Proust's phrases are not crystal clear and logical it is because our psychological life is confused and intelligence penetrates into it through dark corridors with many labyrinthian turns.

The memory of our conscious intelligent self could give him information into past events but emptied of all emotional content which is reconstructed by associative memory.

Talking about his own emotional imprisonment, Lanny Baldwin says: "Emotions choke me, push the tears right behind my eyes, strangle me. It comes like a wave of ecstasy."

"The difference between us is that I ride on this wave when it comes, I never deny it."

In a world that is destroying itself with hatred, I persist in loving, and those who love me are concerned at my defeats.

As soon as he visits his family, Leonard becomes sad, dead, eclipsed. As soon as he comes to see me, it is a reprieve from death in life.

His mother asked him: "Would I like Anais Nin?"

He answered: "You are poles apart."

For the novel: Use iron lung as a symbol of one person breathing through another, living through transfusion of oxygen. Dependence of Djuna on Jay. Any dependence causes anxiety. Because one is living through another and fears the loss of the other. For Lillian it was not her throat, her senses, her life, but all the tasting, touching was done by way of Jay. When he welcomed friends, was at ease in groups, accepted and included all of life, undifferentiated, then she experienced this openness, this total absence of retraction through him. In herself she carried a mechanism which interfered with deep intakes of life and people. Her critical faculty would pass judgment, evaluate, reject, limit. Jay never limited his time or energy. When the time came,

he fell asleep. But Lillian felt she had to forestall such a surrender, because it was public. She had to foresee when her energy would fail, and so she lived by the clock. At twelve she should leave. Even if the evening was just beginning to flower, she had to cut the cord, resist the demands of others, assert a solitary gesture of determination, the opposite of surrender to the current life. Jay permitted himself to be consumed. He was more rested even when he slept less, by his relaxed abandon, than Lillian was from her exertion of control.

Never understood until now why I had to make myself poor enough in Paris to go to the pawnshop. It was because all my friends went there, and I wanted to reach the same level of poverty and denial, to descend with them into the ordeal of parting from loved objects, losing everything. I was never as emotionally united with all of them as when I, too, sat on the hard bench and waited, watching people's eloquent faces, the story of objects, the atmosphere of dispossession and sacrifice.

In describing relationships, rhythm is important: lax or tense; unilateral or multilateral; crystallized or expanded; fixed or mobile; accelerated or slowed down. When deprived of one sense, reliance on others, those who see best, or hear best, or remember best. There is also the vital matter of distance. People do not live in the present always, at one with it. They live at all kinds and manners of distance from it, as difficult to measure as the course of planets. Fears and traumas make their journeys slanted, peripheral, uneven, evasive.

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 5 A Spy in the House of Love

A Spy in the House of Love In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333)

In Favor of the Sensitive Man and Other Essays (Original Harvest Book; Hb333) Collages

Collages Seduction of the Minotaur

Seduction of the Minotaur Children of the Albatross

Children of the Albatross Delta of Venus

Delta of Venus The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3

The Four-Chambered Heart coti-3 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 2 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 1 Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4

Diary of Anais Nin, Volume 4 The Winter of Artifice

The Winter of Artifice Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5

Seduction of the Minotaur coti-5 Children of the Albatross coti-2

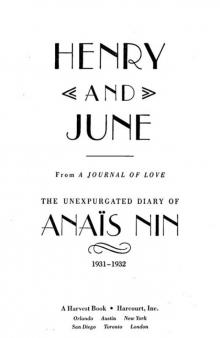

Children of the Albatross coti-2 Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932)

Henry and June: From A Journal of Love -The Unexpurgated Diary of Anaïs Nin (1931-1932) Ladders to Fire

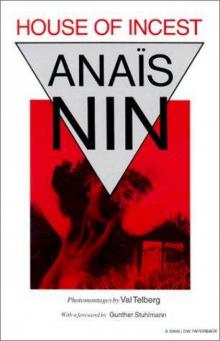

Ladders to Fire House of Incest

House of Incest